take-aways

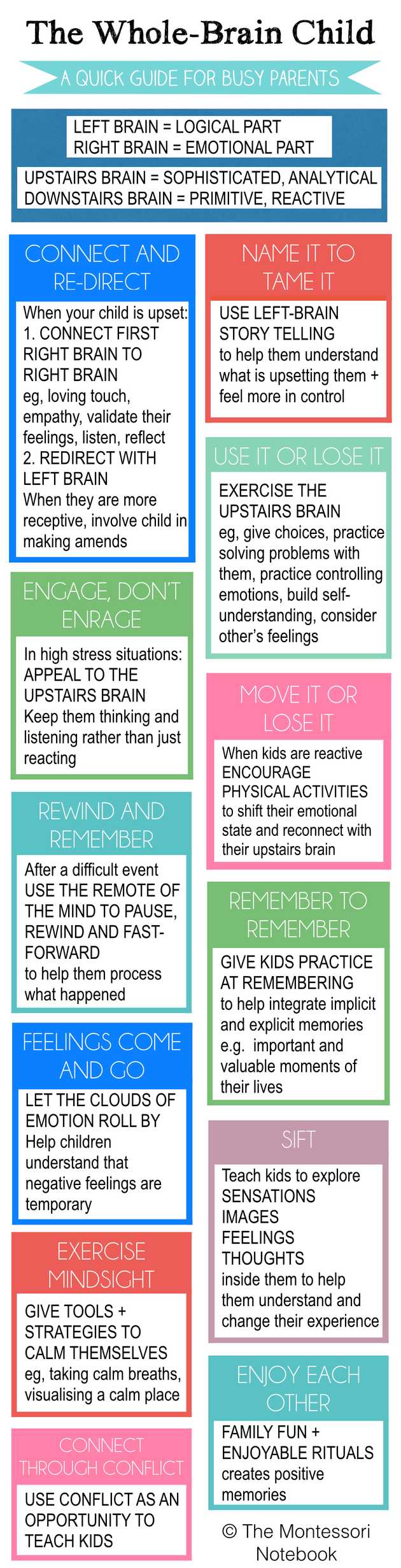

Two Brains Are Better Than One: Integrating the Left and the Right

-

The two sides of our brains are different. The left side likes lists, sequences, logic, language, details, rules, and order. The right side pays attention to nonverbal signals, emotions, images, personal memories, music, art, creativity, and is more connected to the lower brain area that receives, understands, and processes emotional information. The two sides are connected by a bundle of fibers because we need them to work together, to be integrated. Young kids, however, are mostly operating from their right brains because they haven’t developed the abilities to use logic, understand time, use words to express feelings, etc. It’s our role to help them use both sides of their brains. Two strategies will help for kids of any age:

-

How A Child’s Brain Works

-

Analyzing the brain’s integration process is valuable, and can be broken down into five different types. There’s left and right brain integration, vertical and horizontal integration, memory integration, integrating the different parts of self, and finally, integrating self and other.

-

The brain is enormously complex with different areas performing various tasks, yet constantly interlinking. For example, the “reptilian” part of the brain makes split-second survival choices, and the ‘mammalian’ part is more concerned with relationships. Good mental health means getting all areas of the brain to work well together.

-

To “work well together” means all the parts are integrating effectively. Horizontal integration is when the left-brain and right-brain link together. Vertical integration involves the intuitive, more primitive parts of the brain, allowing the more reasonable prefrontal cortex to pause and re-consider a little. Memory integration helps the hippocampus make implicit memories more explicit so that we can process worrying things that have occurred in the past. We can also integrate different thoughts and experiences by focusing our attention differently. And finally, we can develop our kids’ built-in capacity for social connection.

-

Whole brain strategy #1: Connect and Redirect: Surfing Emotional Waves

-

Step 1: Connect with the Right: When kids are experiencing big emotions, they’re operating from their right brain. Logic, language, telling them it isn’t so bad, trying to distract them – none of these strategies will work because they’re left-brain strategies. Instead, use your right brain to connect, to tune in to their emotions, to resonate with your child – acknowledge their feelings. Then and only then –

-

Step 2: Redirect with the Left: Use simple logic and language to suggest solutions to their problems. The authors caution that this does not mean permissiveness, that it takes practice to get good at this strategy, and that you have to maintain your own calm.

-

In other words, connect with your child using a right-brain comment. Katie’s dad acknowledged that she felt sick, and said, ‘And I know that didn’t feel good, did it?’ Only then did he put the story together for Katie, using more logical details. Performing a right-brain to right-brain connection first is known as attunement. Attunement acknowledges feelings using empathetic facial expressions, a compassionate tone of voice, and nonjudgmental listening. It allows our children to ‘feel felt,’ creating a safe space to then address the situation or problem more logically. Once the brain is in a more integrated state, it’s easier to manage the left brain, and solve an issue. It doesn’t mean giving up on boundaries and discipline, nor does it mean solving problems immediately. It just reduces the emotional overload, allowing you to connect and then redirect.

Whole brain strategy #2: Name It to Tame It: Telling Stories to Calm Big Emotions

- Too often we “dismiss and deny” the emotional importance of life’s difficult experiences: we try to talk kids out of their feelings, or we avoid painful issues. Instead, pick a time when you and your child are feeling calm, and have a story-telling conversation about the difficult event. This strategy is integrating both sides of the brain – the left tells the story of the right brain’s strong emotion: taming by naming.

Building the Staircase of the Mind: Integrating the Upstairs and Downstairs Brain

-

We want our children to balance logic and emotions, confront their difficulties, and grow from experiences. When raw emotions do not have the left brain logic to help them, like the emotions Katie was battling with, the bank of chaos looms. On the other hand, if they deny their feelings, the shift is towards the bank of rigidity. We can help our children to build the imaginary staircase between the two levels of the brain, reminding ourselves that a child’s brain is always a work in progress.

-

Imagine the brain as a two-story house. The downstairs brain develops early and is responsible for bodily functions like breathing, as well as for strong emotional reactions like fight (anger), flight (fear), and freeze (fear). There’s a small structure in the downstairs brain that the authors call the “baby gate” of the mind – it causes us to react emotionally without thinking. Sometimes this is good, especially when we feel passionate about someone or thing; often it gets us into trouble (when we react instead of respond to experiences that aren’t life-threatening). The upstairs brain (the top part of your cortex, especially the area behind your forehead) develops later in childhood and on into adulthood; it’s the place where mental processes happen – good decisions, self understanding, emotional and bodily control, empathy, a sense of right and wrong, etc. All the actions we hope kids will take require the upstairs brain, which isn’t fully on-line yet, but we can still appeal to it using the following strategies:

Whole brain strategy #3: Engage, Don’t Enrage: Appealing to the Upstairs Brain

-

First make sure you have applied step 1 of Strategy 1 and connect. Then, once calm, help them find solutions to their challenges. Engage their upstairs brain in problem-solving.

-

Here we have to ask ourselves which side of the brain we want to appeal to. If tension is building, it may help to engage the upstairs brain instead of trying to halt the rage brewing in the downstairs brain. So when you can see that your child is about to lose it, you can ask for more precise words for how they feel, and then maybe ask them to come up with a compromise that works for everybody, or start negotiating

Whole brain strategy #4: Use It or Lose It: Exercising the Upstairs Brain

-

“A strong upstairs brain balances out the downstairs brain, and is essential for social-emotional intelligence.” So throughout the day look for opportunities to help your child practice upstairs brain skills:

-

Making decisions: For toddlers, give choices about what to wear, what to drink, etc. For older kids, let them, with support and guidance, make more difficult choices about conflicting schedules or desires. Don’t rescue them, even if you can foresee that their choice might lead to their regret. However, help them predict possible outcomes.

-

Regulating emotions and the body: Be sure and model this yourself in all your interactions with your kids. Teach them calming techniques like taking a deep breath (“Swallow a bubble,” “Take a belly breath.”). Older kids can learn to count to ten, or take a mental time-out. Self-understanding: Ask kids questions that help them think about and reflect on their feelings, help them predict what they might feel in a new situation & how they might handle it. Also, model this for them by using self-talk out loud, “Hmmm. I seem to feel extra nervous. I wonder why? Maybe it’s because I don’t know what my boss will say when I ask for time off.”

-

Empathy: Ask kids questions about the feelings of others, about what someone’s actions might suggest about how they feel, about what might make someone feel better, etc. Show compassion and empathy yourself.

-

Morality: This isn’t just knowing what’s right and wrong but understanding how actions impact the greater good. We want our kids to do the right thing with compassion, kindness, and empathy – not because someone’s watching, but because they know right from wrong. The authors give examples of questions and situations to develop this.

-

Third aspect of integration involves memory

-

Memories aren’t like photocopy machines that produce accurate pictures of what took place in the past. The hippocampus stores memory with an overlay of emotion, and our memories always coexist with the feelings we attach to an event. Memory also isn’t like a filing cabinet, where we simply pull them out when we need to.

-

Children associate past experiences with what might happen in the future. They then react accordingly. Once an implicit memory is spoken about and understood, it becomes explicit and, therefore, easier to deal with any fears they may have. Children don’t just forget about difficult experiences; we have to help them understand what happened, and how they felt about it. Then, just like a jigsaw puzzle, put all the pieces together.

Whole brain strategy #5: Move It or Lose It: Moving the Body to Avoid Losing the Mind

- Movement changes brain chemistry, so when kids are near a breaking point and aren’t connecting with their upstairs brain, get them moving to integrate their brain. The same is true for adults.

Kill the Butterflies! Integrating Memory for Growth and Healing

- Memories are tricky because they’re not just experiences filed away in a file cabinet, exactly as they happened. And they’re not exact photocopies of the experience, either. In this chapter you’ll learn about two different kinds of memory, and how to help your kids (and yourself) integrate them. If we don’t help our kids integrate their difficult memories, their emotions will show up in their behavior – which can confuse both them and us. And it’s important to remember that what’s a challenging memory for a child might seem pretty harmless to us. The authors use cute cartoon drawings and catchy sayings to illustrate the strategies:

Whole brain strategy #6: Use the Remote of the Mind: Replaying Memories

- Just as telling a “story” or narrative about a strong emotion is naming it to tame it, here we help kids get in touch with their unhappy and challenging memories to integrate them. The authors suggest we guide kids to think of their minds as a remote control that can fast-forward, skip, pause, and stop when remembering painful experiences. As adults, we should help them “rewind and remember” instead of “fast-forward and forget.”

Whole brain strategy #7: Remembering to Remember: Making Recollection a Part of Your Family’s Daily Life

- Make daily family conversations a habit so kids always have a chance to talk about their experiences and memories. Ask open-ended questions that will get them thinking and encourage them to share more than a “yes” or “no.” Instead of the usual, “How was your day?” ask them questions like, “What was your favorite part of the day?” and “Tell me about recess.” Ask them about their not-so favorite parts of the day, too. Print those digital photos and make books and albums for your kids so you can talk about shared experiences together. Have a regular family movie night where you watch movies you’ve made of your kids, family, and experiences.

The United States of Me: Integrating the Many Parts of the Self

-

In this chapter the authors introduce the idea of “Mindsight,” a term coined by Dan Siegel that mean understanding our own minds, which then we can then use to understand the minds of others. In this chapter you’ll read how to teach kids about the wheel of awareness, telling the difference between what they feel and who they are, learn to focus their attention, and learn to get back to their hub (center). This will help them develop Mindsight. Most of these concepts are for K-12 kids, but you yourself will benefit from applying them to your own mind. By modeling this for younger kids, you’ll be preparing them to use Mindsight as they get older.

-

We can help children to integrate their memories, feelings, and thoughts in order to understand their minds. When they learn that they have some choice about how they feel or respond to situations, it’s very empowering.

Whole brain strategy #8: Let the Clouds of Emotion Roll By: Teaching That Feelings Come and Go

- Teaching kids to get in touch with and verbalize their feelings is a good strategy. But it’s also important to teach them that feelings are temporary and changeable, like the weather. This helps them put feelings in perspective – they won’t last forever. This will help them regain a calm state more easily and maintain it when painful feelings come along.

Whole brain strategy #9: SIFT: Paying Attention to What’s Going On Inside

-

Teach kids to know what’s on the rim of their wheel of awareness and focus their attention on the following: the Sensations (messages) their body sends them; the Images they have from their experiences and imagination (from the right brain); the Feelings they have (right brain); and the Thoughts they are using to understand their world (left brain). This process is the basis for Mindsight and the chapter has strategies to make it fun.

-

SIFT is the acronym for sensations, images, feelings, and thoughts. We can use this acronym to help children sort through physical sensations such as butterflies in the tummy, images that might be worrying them, such as an embarrassing moment at school, and feelings. It helps if they have a broad “feeling” vocabulary, so they can use specific words like “disappointed,” as opposed to a more general one like feeling “sad.”

-

Children can also learn that they don’t have to believe all their thoughts. We can encourage them to argue with the ones that may not be true. And we can teach them strategies that calm them, like visualization techniques or imagining a place where they feel calm and peaceful. If they can access a sense of stillness and calm, they can learn to separate from and manage the storms that brew around them.

Whole brain strategy #10: Exercise Mindsight: Getting Back to the Hub

- By teaching kids that they can choose how to think and feel about what happens to them in life, that they aren’t victims, that they can use their mind to calm their brain, they’ll thrive. The authors present ways to help kids get in touch with their “hub,” that peaceful, calm center.

The Me-We Connection: Integrating Self and Other

-

We need to help kids develop the second aspect of Mindsight – to integrate self and other – and develop relationships based on kindness, compassion, and empathy. Using the Mindsight skills they’re learning, with help from you and the developmental process, they can now learn to combine insight with empathy to develop interpersonal integration. It’s up to adults to create positive relationships with kids; to encourage them to make friends and form relationships by helping them be receptive instead of reactive, and to use Mindsight skills with others.

-

Sometimes children need a little bit of help with their empathy and to recognize others’ needs and perspectives. Enter the fascinating discovery of mirror neurons. Our brains are activated to respond to the actions of somebody else. We can nurture this built-in wiring in our children to create more empathy. For example, if we see someone in tears, we often become tearful too. Our bodies automatically respond to someone else’s emotions and actions. We mirror them. Hence, our kids can learn to empathize with others, without losing their sense of who they are.

Whole brain strategy #11: Increase the Family Fun Factor: Making a Point to Enjoy Each Other

- Spend time having fun, playing, and enjoying each other’s company. Every time you have enjoyable experiences with kids, their brains release a “reward” chemical called dopamine, and they learn that relationships are rewarding. You’ve probably tried some of the suggestions to implement this strategy – and if you haven’t, the time to start is now!

Whole brain strategy #12: Connection Through Conflict: Teach Kids to Argue with a “We” in Mind

-

Conflict is unavoidable in relationships, so teach kids how to handle it in helpful ways using Mindsight: 1. recognize others’ perspectives and viewpoints (teach them previous strategies); 2. teach them to understand nonverbal cues so they can attune with others; 3. teach them to repair the relationship after conflict.

-

If our children argue or complain about something someone said to them, we can ask them to explore the other person’s perspective. They can look at why they thought this person responded differently, and explore another’s reactions without being defensive. They can observe someone’s non-verbal behavior to understand what emotions they might have. We can also teach them to fix things after a fight by discussing how they can make amends. This could be through a kind act, or a letter of apology.