take-aways

-

Rationality

- Rationality is logical coherence—reasonable or not. Econs are rational by this definition, but there is overwhelming evidence that Humans cannot be. An Econ would not be susceptible to priming, WYSIATI, narrow framing, the inside view, or preference reversals, which Humans cannot consistently avoid.

- The definition of rationality as coherence is impossibly restrictive; it demands adherence to rules of logic that a finite mind is not able to implement.

- The assumption that agents are rational provides the intellectual foundation for the libertarian approach to public policy: do not interfere with the individual’s right to choose, unless the choices harm others.

- Thaler and Sunstein advocate a position of libertarian paternalism, in which the state and other institutions are allowed to nudge people to make decisions that serve their own long-term interests. The designation of joining a pension plan as the default option is an example of a nudge.

-

Two Systems

- What can be done about biases? How can we improve judgments and decisions, both our own and those of the institutions that we serve and that serve us? The short answer is that little can be achieved without a considerable investment of effort. As I know from experience, System 1 is not readily educable. Except for some effects that I attribute mostly to age, my intuitive thinking is just as prone to overconfidence, extreme predictions, and the planning fallacy as it was before I made a study of these issues. I have improved only in my ability to recognize situations in which errors are likely: “This number will be an anchor…,” “The decision could change if the problem is reframed…” And I have made much more progress in recognizing the errors of others than my own

- The way to block errors that originate in System 1 is simple in principle: recognize the signs that you are in a cognitive minefield, slow down, and ask for reinforcement from System 2.

- Organizations are better than individuals when it comes to avoiding errors, because they naturally think more slowly and have the power to impose orderly procedures. Organizations can institute and enforce the application of useful checklists, as well as more elaborate exercises, such as reference-class forecasting and the premortem.

- At least in part by providing a distinctive vocabulary, organizations can also encourage a culture in which people watch out for one another as they approach minefields.

- The corresponding stages in the production of decisions are the framing of the problem that is to be solved, the collection of relevant information leading to a decision, and reflection and review. An organization that seeks to improve its decision product should routinely look for efficiency improvements at each of these stages.

- There is much to be done to improve decision making. One example out of many is the remarkable absence of systematic training for the essential skill of conducting efficient meetings.

- Ultimately, a richer language is essential to the skill of constructive criticism.

- Decision makers are sometimes better able to imagine the voices of present gossipers and future critics than to hear the hesitant voice of their own doubts. They will make better choices when they trust their critics to be sophisticated and fair, and when they expect their decision to be judged by how it was made, not only by how it turned out.

-

how much do we know?

-

what did our brains evolve to do?

-

Most of us think we know more than we actually do. We think this because we ignore complexity and believe that our brain, like a computer, is designed to store information. This isn’t the case. Rather, our brains evolved to work with other brains and to engage in collaborative activities. Indeed, it’s our ability to divide cognitive labor and share intentionality that’s led to our species’s success. So, when thinking about intelligence, we should take into account people’s collaborative aptitude, and we’d do well to encourage more collaboration – not just in school, but in society as a whole.

-

Don’t let the illusion of explanatory depth drain your bank account.

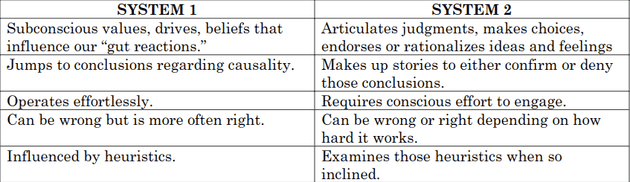

2 Systems

-

The Characters of the Story

-

System 1 (fast thinker) operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.

-

System 2 (slow thinker) allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration.

-

I describe System 1 as effortlessly originating impressions and feelings that are the main sources of the explicit beliefs and deliberate choices of System 2. The automatic operations of System 1 generate surprisingly complex patterns of ideas, but only the slower System 2 can construct thoughts in an orderly series of steps.

-

In rough order of complexity, here are some examples of the automatic activities that are attributed to System 1:

- Detect that one object is more distant than another.

- Orient to the source of a sudden sound.

-

The highly diverse operations of System 2 have one feature in common: they require attention and are disrupted when attention is drawn away. Here are some examples:

- Focus on the voice of a particular person in a crowded and noisy room.

- Count the occurrences of the letter a in a page of text.

- Check the validity of a complex logical argument.

- It is the mark of effortful activities that they interfere with each other, which is why it is difficult or impossible to conduct several at once.

- The gorilla study illustrates two important facts about our minds: we can be blind to the obvious, and we are also blind to our blindness.

- One of the tasks of System 2 is to overcome the impulses of System 1. In other words, System 2 is in charge of self-control.

- The best we can do is a compromise: learn to recognize situations in which mistakes are likely and try harder to avoid significant mistakes when the stakes are high.

-

-

Attention and Effort

- People, when engaged in a mental sprint, become effectively blind.

- As you become skilled in a task, its demand for energy diminishes. Talent has similar effects.

- One of the significant discoveries of cognitive psychologists in recent decades is that switching from one task to another is effortful, especially under time pressure.

Problems switching to system 2

The Lazy Controller

- It is now a well-established proposition that both self-control and cognitive effort are forms of mental work. Several psychological studies have shown that people who are simultaneously challenged by a demanding cognitive task and by a temptation are more likely to yield to the temptation.

- People who are cognitively busy are also more likely to make selfish choices, use sexist language, and make superficial judgments in social situations. A few drinks have the same effect, as does a sleepless night.

- Baumeister’s group has repeatedly found that an effort of will or self-control is tiring; if you have had to force yourself to do something, you are less willing or less able to exert self-control when the next challenge comes around. The phenomenon has been named ego depletion.

- The evidence is persuasive: activities that impose high demands on System 2 require self-control, and the exertion of self-control is depleting and unpleasant. Unlike cognitive load, ego depletion is at least in part a loss of motivation. After exerting self-control in one task, you do not feel like making an effort in another, although you could do it if you really had to. In several experiments, people were able to resist the effects of ego depletion when given a strong incentive to do so.

- Restoring glucose levels can have a counteracting effect to mental depletion.

The Associative Machine/Priming

- Priming effects take many forms. If the idea of EAT is currently on your mind (whether or not you are conscious of it), you will be quicker than usual to recognize the word SOUP when it is spoken in a whisper or presented in a blurry font. And of course you are primed not only for the idea of soup but also for a multitude of food-related ideas, including fork, hungry, fat, diet, and cookie.

- Priming is not limited to concepts and words; your actions and emotions can be primed by events of which you are not even aware, including simple gestures.

- Money seems to prime individualism: reluctance to be involved with, depend on, or accept demands from others.

- Note: the effects of primes are robust but not necessarily large; likely only a few in a hundred voters will be affected.

- Priming happens when exposure to one idea makes you more likely to favor related ones.

- For example, when asked to complete the word fragment SO_P, people primed with ‘eat’ will usually complete SOUP. Meanwhile, people primed with ‘wash’ will usually complete SOAP.

- System 1 helps us make quick connections between causes and effects, things and their properties, and categories. By priming us (i.e., “pre-fetching” information based on recent stimuli and pre-existing associations) System 1 helps us make rapid sense of the infinite network of ideas that fills our sensory world, without having to analyze everything.

- Priming usually works because the most familiar answer is also the most likely. But priming causes issues when System 2 leans on these associations inappropriately.

- Instead of considering all options equally, System 1 gives ‘primed’ associations priority instead of relying on facts.

Cognitive Ease

-

Cognitive ease: no threats, no major news, no need to redirect attention or mobilize effort.

-

Cognitive strain: affected by both the current level of effort and the presence of unmet demands; requires increased mobilization of System 2.

-

Memories and thinking are subject to illusions, just as the eyes are.

-

Predictable illusions inevitable occur if a judgement is based on an impression of cognitive ease or strain.

-

A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth.

-

If you want to make recipients believe something, general principle is to ease cognitive strain: make font legible, use high-quality paper to maximize contrasts, print in bright colours, use simple language, put things in verse (make them memorable), and if you quote, make sure it’s an easy name to pronounce.

-

Weird example: stocks with pronounceable tickers do better over time.

-

Mood also affects performance: happy moods dramatically improve accuracy. Good mood, intuition, creativity, gullibility and increased reliance on System 1 form a cluster.

-

At the other pole, sadness, vigilance, suspicion, an analytic approach, and increased effort also go together. A happy mood loosens the control of System 2 over performance: when in a good mood, people become more intuitive and more creative but also less vigilant and more prone to logical errors.

-

Cognitive Ease describes how hard we think a mental task is.

-

It increases if the information is clear, simple, and repeated.

-

Biases happen when complex information (requiring System 2) is presented in ways that make problems look easier than they really are (falling back on System 1).

-

For example, researchers gave students the following puzzle: “A bat and ball cost $1.10. The bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

- The question is not straightforward and needs System 2 to engage. But researchers found that System 1 often responds with an intuitive, incorrect answer of 10 cents (correct = 5 cents).

- Interestingly, when the students saw the question in a less legible font, cognitive ease decreased. Far fewer made the error because System 2 was more likely to engage.

-

Because we try to conserve mental energy, if cognitive ease is high, and our brain thinks it can solve a problem with System 1, it will not switch to System 2.

-

Note: Advertising has long used this technique to persuade people to make instinctive purchase decisions. A good mood can also fool us into a state of cognitive ease.

COHERENT STORIES (ASSOCIATIVE COHERENCE). Norms, Surprises, and Causes

- We can detect departures from the norm (even small ones) within two-tenths of a second.

- To make sense of the world we tell ourselves stories about what’s going on. We make associations between events, circumstances, and regular occurrences. The more these events fit into our stories the more normal they seem.

- Things that don’t occur as expected take us by surprise. To fit those surprises into our world we tell ourselves new stories to make them fit. We say, “Everything happens for a purpose,” “God did it,” “That person acted out of character,” or “That was so weird it can’t be random chance.” Abnormalities, anomalies, and incongruities in daily living beg for coherent explanations. Often those explanations involve 1) assuming intention, “It was meant to happen,” 2) causality, “They’re homeless because they’re lazy,” or 3) interpreting providence, “There’s a divine purpose in everything.” “We are evidently ready from birth to have impressions of causality, which do not depend on reasoning about patterns of causation,” (page 76). “Your mind is ready and even eager to identify agents, assign them personality traits and specific intentions, and view their actions as expressing individual propensities,” (page 76). Potential for error? We posit intention and agency where none exists, we confuse causality with correlation, and we make more out of coincidences than is statistically warranted.

- System 1 uses norms to maintain our model of the world, and constantly updates them. They tell us what to expect in a given context.

- Surprises should trigger the activation of System 2 because they are outside of these models. But if new information is presented in familiar contexts or patterns, System 1 can fail to detect this and fall back on old ‘norms’.

- For example, when asked “How many animals of each kind did Moses take into the ark?”, many people immediately answer “two”. They do not recognize what is wrong because the words fit the norm of a familiar biblical context (but Moses ≠ Noah).

- Failing to create new norms appropriately causes us to construct stories that explain situations and ‘fill in the gaps’ based on our existing beliefs. This leads to false explanations for coincidences, or events with no correlation (also known as ‘narrative fallacy’).

Exaggerated Emotional Coherence/Halo Effect

- The halo effect is confirmation bias towards people. It’s why first impressions count.

- In one study, experimenters gave people lists of traits for fictitious characters and found that participants’ overall views changed significantly just based on the order of the traits (positive or negative first).

- The halo effect also stretches to unseen attributes that are unknowable and unrelated to the initial interaction.

- For example, friendly people are also considered more likely to donate to charity and tall people are perceived as more competent (which may help explain the unexpectedly high number of tall CEOs in the world’s largest companies).

- System 1 struggles to account for the possibility that contradictory information may exist that we cannot see. It operates on the principle that “what you see is what you get”.

- If you like the president’s politics, you probably like his voice and his appearance as well. The tendency to like (or dislike) everything about a person—including things you have not observed—is known as the halo effect.

- To counter, you should decor relate error - in other words, to get useful information from multiple sources, make sure these sources are independent, then compare.

- The principle of independent judgments (and decorrelated errors) has immediate applications for the conduct of meetings, an activity in which executives in organizations spend a great deal of their working days. A simple rule can help: before an issue is discussed, all members of the committee should be asked to write a very brief summary of their position.

Confirmation Bias

- Confirmation bias is our tendency to favor facts that support our existing conclusions and unconsciously seek evidence that aligns with them.

- Our conclusions can come from existing beliefs or values, or System 1 norms. They can also come from an idea provided to us as a System1 prime.

- For example, if we believe that “Republicans are out to destroy our way of life”, we’ll subconsciously pay more attention and give more credit to evidence that confirms that belief while dismissing evidence that contradicts it. (And vice versa for Democrats.)

- Confirmation bias affirms System 1 norms and priming. System 1 tends to prioritise evidence that supports pre-existing ideas. It will also discount evidence that contradicts them.

- The operations of associative memory contribute to a general confirmation bias. When asked, “Is Sam friendly?” different instances of Sam’s behavior will come to mind than would if you had been asked “Is Sam unfriendly?” A deliberate search for confirming evidence, known as positive test strategy, is also how System 2 tests a hypothesis. Contrary to the rules of philosophers of science, who advise testing hypotheses by trying to refute them, people (and scientists, quite often) seek data that are likely to be compatible with the beliefs they currently hold.

intuitive judgments

-

System 1 helps us make quick, sometimes life-saving judgements.

-

From an evolutionary sense, this helped us scan for and avoid threats. But System 1 also has blind spots that can lead to poor analysis.

-

For example, System 1 is good at assessing averages but very poor at determining cumulative effects. When shown lines of different lengths, it is very easy for people to estimate the average length. It is very difficult for them to estimate the total length.

-

System 1 also can’t “forget” matches that have nothing to do with the question and interfere with the answer. In one study participants were given a story about a particularly gifted child. Most readily answered the question “How tall is a man who is as tall as the child was clever?” even though there is no logical way of estimating the answer.

-

Intuitive assessments can be so strong they override our thought process even when we know System 2 should be making the decision. For example, when voters base their decision on candidates’ photos.

-

What You See is All There is (WYSIATI)

- The measure of success for System 1 is the coherence of the story it manages to create. The amount and quality of the data on which the story is based are largely irrelevant. When information is scarce, which is a common occurrence, System 1 operates as a machine for jumping to conclusions.

- WYSIATI: What you see is all there is.

- WYSIATI helps explain some biases of judgement and choice, including:

- Overconfidence: As the WYSIATI rule implies, neither the quantity nor the quality of the evidence counts for much in subjective confidence. The confidence that individuals have in their beliefs depends mostly on the quality of the story they can tell about what they see, even if they see little.

- Framing effects: Different ways of presenting the same information often evoke different emotions. The statement that the odds of survival one month after surgery are 90% is more reassuring than the equivalent statement that mortality within one month of surgery is 10%.

- Base-rate neglect: Recall Steve, the meek and tidy soul who is often believed to be a librarian. The personality description is salient and vivid, and although you surely know that there are more male farmers than male librarians, that statistical fact almost certainly did not come to your mind when you first considered the question.

Substitution/Answering an Easier Question

- We often generate intuitive opinions on complex matters by substituting the target question with a related question that is easier to answer.

- The present state of mind affects how people evaluate their happiness.

- affect heuristic: in which people let their likes and dislikes determine their beliefs about the world. Your political preference determines the arguments that you find compelling.

- If you like the current health policy, you believe its benefits are substantial and its costs more manageable than the costs of alternatives.

- Substitution is what happens when we conserve mental energy by replacing difficult questions with easier, related questions. This makes System 1 respond with a ‘mental shotgun’, and we fail to recognize that System 2 should be analyzing the problem.

- For example, “How popular will the president be six months from now?” is substituted with “How popular is the president right now?” System 1 recalls the answer to the easier question with more cognitive ease.

- Substitution happens more often when we’re emotional. For example, “How much would you contribute to save an endangered species?” is replaced with “How much emotion do you feel when you think of dying dolphins?”. System 1 matches giving money with the strength of emotion, even though the two are not directly related.

The Law of Small Numbers

- A random event, by definition, does not lend itself to explanation, but collections of random events do behave in a highly regular fashion.

- Large samples are more precise than small samples.

- Small samples yield extreme results more often than large samples do.

- A Bias of Confidence Over Doubt

- The strong bias toward believing that small samples closely resemble the population from which they are drawn is also part of a larger story: we are prone to exaggerate the consistency and coherence of what we see.

- Cause and Chance

- Our predilection for causal thinking exposes us to serious mistakes in evaluating the randomness of truly random events.

- The law of small numbers is when System 1 tries to explain results that are an effect of statistically small samples. This leads to System 1 inventing stories, connections and causal links that don’t exist.

- For example, a study found that rural areas have both the lowest and highest rates of kidney cancer. This provoked theories about why small populations cause or prevent cancer, even though there is no link.

- System 1 also tries to explain random results that appear to have a pattern. For example, in a sequence of coin toss results, TTTT is just as likely as TTTH. But the pattern in the first set triggers a search for a reason more than the second.

Anchoring Effects

- The phenomenon we were studying is so common and so important in the everyday world that you should know its name: it is an anchoring effect. It occurs when people consider a particular value for an unknown quantity before estimating that quantity. What happens is one of the most reliable and robust results of experimental psychology: the estimates stay close to the number that people considered—hence the image of an anchor.

- The Anchoring Index

- The anchoring measure would be 100% for people who slavishly adopt the anchor as an estimate, and zero for people who are able to ignore the anchor altogether. The value of 55% that was observed in this example is typical. Similar values have been observed in numerous other problems.

- Powerful anchoring effects are found in decisions that people make about money, such as when they choose how much to contribute to a cause.

- In general, a strategy of deliberately “thinking the opposite” may be a good defense against anchoring effects, because it negates the biased recruitment of thoughts that produces these effects.

- Anchoring is when we start our analysis and struggle to move away from an initially suggested answer.

- When given a starting point for a solution, System 2 will “anchor” its answer to this figure. It will then analyse whether the true value should be lower or higher.

- For example, a sign in a shop that says “Limit of 12 per person” will cause people to take more items than a sign that says “No limit per person.”

- The customers anchor their purchase decision to the number 12 because they are primed by System 1. We don’t start from a neutral point when deducing the solution and System 2 starts from a bias. This technique is exploited in real estate sales and all other forms of negotiation.

Availability

-

The availability heuristic, like other heuristics of judgment, substitutes one question for another: you wish to estimate the size of a category or the frequency of an event, but you report an impression of the ease with which instances come to mind. Substitution of questions inevitably produces systematic errors.

-

You can discover how the heuristic leads to biases by following a simple procedure: list factors other than frequency that make it easy to come up with instances. Each factor in your list will be a potential source of bias.

-

Resisting this large collection of potential availability biases is possible, but tiresome. You must make the effort to reconsider your impressions and intuitions by asking such questions as, “Is our belief that thefts by teenagers are a major problem due to a few recent instances in our neighborhood?” or “Could it be that I feel no need to get a flu shot because none of my acquaintances got the flu last year?” Maintaining one’s vigilance against biases is a chore—but the chance to avoid a costly mistake is sometimes worth the effort.

-

The Psychology of Availability

- For example, people:

- believe that they use their bicycles less often after recalling many rather than few instances

- are less confident in a choice when they are asked to produce more arguments to support it

- are less confident that an event was avoidable after listing more ways it could have been avoided

- are less impressed by a car after listing many of its advantages

- The difficulty of coming up with more examples surprises people, and they subsequently change their judgement.

- For example, people:

-

The following are some conditions in which people “go with the flow” and are affected more strongly by ease of retrieval than by the content they retrieved:

- when they are engaged in another effortful task at the same time

- when they are in a good mood because they just thought of a happy episode in their life

- if they score low on a depression scale

- if they are knowledgeable novices on the topic of the task, in contrast to true experts

- when they score high on a scale of faith in intuition

- if they are (or are made to feel) powerful

-

Availability bias happens when our thinking is influenced by our ability to recall examples.

-

System 1 can recall memories better than other evidence because of the cognitive ease heuristic. This makes them feel truer than facts and figures and System 2 will give them more weight.

-

For example, we overestimate our contribution to group activities. The memory of ourselves completing a task is easier to recall than the memory of someone else doing it.

-

Availability also influences our estimation of risk. People’s experiences, or exposure through the media, cause most people to overestimate the likelihood and severity of otherwise rare risks and accidents.

-

The affect heuristic is an instance of substitution, in which the answer to an easy question (How do I feel about it?) serves as an answer to a much harder question (What do I think about it?).

-

Experts sometimes measure things more objectively, weighing total number of lives saved, or something similar, while many citizens will judge “good” and “bad” types of deaths.

-

An availability cascade is a self-sustaining chain of events, which may start from media reports of a relatively minor event and lead up to public panic and large-scale government action.

-

The Alar tale illustrates a basic limitation in the ability of our mind to deal with small risks: we either ignore them altogether or give them far too much weight—nothing in between.

-

In today’s world, terrorists are the most significant practitioners of the art of inducing availability cascades.

-

Psychology should inform the design of risk policies that combine the experts’ knowledge with the public’s emotions and intuitions.

Representativeness

-

Representations form when the stories and norms established by System 1 become inseparable from an idea. System 2 weighs System 1 representations more than evidence.

-

In one study, people were asked to give the probability that an example student would choose to study a particular degree. They paid more attention to the description of their character than statistics on student numbers. The “people who like sci-fi also like computer science” stereotype had more impact than “only 3% of graduates study computer science”.

-

The representativeness heuristic is involved when someone says “She will win the election; you can see she is a winner” or “He won’t go far as an academic; too many tattoos.”

-

One sin of representativeness is an excessive willingness to predict the occurrence of unlikely (low base-rate) events. Here is an example: you see a person reading The New York Times on the New York subway. Which of the following is a better bet about the reading stranger?

- She has a PhD.

- She does not have a college degree.

- Representativeness would tell you to bet on the PhD, but this is not necessarily wise. You should seriously consider the second alternative, because many more nongraduates than PhDs ride in New York subways.

-

The second sin of representativeness is insensitivity to the quality of evidence.

-

There is one thing you can do when you have doubts about the quality of the evidence: let your judgments of probability stay close to the base rate.

-

The essential keys to disciplined Bayesian reasoning can be simply summarized:

- Anchor your judgment of the probability of an outcome on a plausible base rate.

- Question the diagnosticity of your evidence.

Linda: Less is More/The Conjunction Fallacy

- When you specify a possible event in greater detail you can only lower its probability. The problem therefore sets up a conflict between the intuition of representativeness and the logic of probability.

- conjunction fallacy: when people judge a conjunction of two events to be more probable than one of the events in a direct comparison.

- Representativeness belongs to a cluster of closely related basic assessments that are likely to be generated together. The most representative outcomes combine with the personality description to produce the most coherent stories. The most coherent stories are not necessarily the most probable, but they are plausible, and the notions of coherence, plausibility, and probability are easily confused by the unwary.

- The conjunction fallacy, or the Linda problem, happens because System 1 prefers more complete stories (over simpler alternatives).

- A scenario with more variables is less likely to be true. But because it provides a more complete and persuasive argument for System 1, System 2 can falsely estimate that it is more likely.

- For example, a woman (‘Linda’) was described to participants in a study as “single, outspoken and very bright”. They were more likely to categorize her as a “bank teller who is an active feminist” than “a bank teller”.

- It is less probable that someone would belong in the first category (since it requires two facts to be true), but it feels truer. It fits with the norm that System 1 has created around Linda.

- Note: This is why we struggle so much with Occam’s Razor

Causes Trump Statistics

-

The Causes Trump Statistics bias is caused by System 1 preferring stories over numbers.

-

For example, people were told that only 27% of subjects in an experiment went to help someone who sounded like they were choking in the next booth. Despite this low statistic, people predicted that subjects that appeared to be nice would be much more likely to help.

-

System 1 places more importance on causal links, than statistics.

-

A surprising anecdote of an individual case has more influence on our judgment than a surprising set of statistics. Some people were not told the results of the choking experiment but were told that the nice interviewees did not help. Their predictions of the overall results were then fairly accurate.

-

An extension to this bias is that we put more faith in statistics that are presented in a way that easily links cause and effect.

-

People in a study were told 85% of cars involved in accidents are green. This statistic was cited more in decision-making about car crashes than if participants were told that 85% of cabs in a city are green.

-

Statistically, the evidence is the same (if 85% of cars are green and cars of all colours crash equally then 85% of crashes will involve green cars) but one is more readily believed because it is structured to appeal to our love of storytelling.

Regression to the Mean

-

An important principle of skill training: rewards for improved performance work better than punishment of mistakes. This proposition is supported by much evidence from research on pigeons, rats, humans, and other animals.

-

Talent and Luck

- My favourite equations:

- success = talent + luck

- great success = a little more talent + a lot of luck

-

Understanding Regression

- The general rule is straightforward but has surprising consequences: whenever the correlation between two scores is imperfect, there will be regression to the mean.

- If the correlation between the intelligence of spouses is less than perfect (and if men and women on average do not differ in intelligence), then it is a mathematical inevitability that highly intelligent women will be married to husbands who are on average less intelligent than they are (and vice versa, of course).

-

Failure to expect a regression to the mean is a bias that causes us to try to find plausible explanations for reversions from high or low performance.

-

Probability tells us that abnormally high (or low) results are most likely to be followed by a result that’s closer to the overall mean than another extreme result. But the tendency of System 1 to look for causal effects, makes people disregard averages and look for stories.

-

For example, the likelihood of a person achieving success in a particular sporting event is a combination of talent and chance. Average performance is the mean performance over time.

-

This means an above (or below) average result on one day is likely to be followed by a more average performance the next. This has nothing to do with the above-average result. It’s just that if the probability of good performance follows a normal distribution then a result that tracks the mean will always be more likely than another extreme result.

- But people will try to find an explanation, such as high performance on the first day creates pressure on the second day. Or that high performance on the first day is the start of a “streak” and high performance on the second day is expected.

Taming Intuitive Predictions

- Some predictive judgements, like those made by engineers, rely largely on lookup tables, precise calculations, and explicit analyses of outcomes observed on similar occasions. Others involve intuition and System 1, in two main varieties:

- Some intuitions draw primarily on skill and expertise acquired by repeated experience. The rapid and automatic judgements of chess masters, fire chiefs, and doctors illustrate these.

- Others, which are sometimes subjectively indistinguishable from the first, arise from the operation of heuristics that often substitute an easy question for the harder one that was asked.

- We are capable of rejecting information as irrelevant or false, but adjusting for smaller weaknesses in the evidence is not something that System 1 can do. As a result, intuitive predictions are almost completely insensitive to the actual predictive quality of the evidence.

- A Correction for Inuitive Predictions

- Recall that the correlation between two measures—in the present case reading age and GPA—is equal to the proportion of shared factors among their determinants. What is your best guess about that proportion? My most optimistic guess is about 30%. Assuming this estimate, we have all we need to produce an unbiased prediction. Here are the directions for how to get there in four simple steps:

- Start with an estimate of average GPA.

- Determine the GPA that matches your impression of the evidence.

- Estimate the correlation between your evidence and GPA.

- If the correlation is .30, move 30% of the distance from the average to the matching GPA.

- Despite the pitfalls of relying on the intuitions of System 1, System 2 cannot function without it. We are often faced with problems where information is incomplete, and we need to estimate to come up with an answer.

- Kahneman suggests the following process for overcoming the inaccuracies of System 1:

- Start from a ‘base’ result by looking at average or statistical information.

- Separately, estimate what you would expect the result to be based on your beliefs and intuitions about the specific scenario.

- Estimate what the correlation is between your intuitions and the outcome you are predicting.

- Apply this correlation to the difference between the ‘base’ and your intuitive estimate.

- It is vital that we activate System 2 when trying to predict extreme examples, and avoid relying on the intuition that System 1 provides us with.

The Illusion of Understanding/Hindsight bias

- From Taleb: narrative fallacy: our tendency to reshape the past into coherent stories that shape our views of the world and expectations for the future.

- As a result, we tend to overestimate skill, and underestimate luck.

- Once humans adopt a new view of the world, we have difficulty recalling our old view, and how much we were surprised by past events.

- Outcome bias: our tendency to put too much blame on decision makers for bad outcomes vs. good ones.

- This both influences risk aversion, and disproportionately rewarding risky behaviour (the entrepreneur who gambles big and wins).

- At best, a good CEO is about 10% better than random guessing.

- Hindsight Bias is caused by overconfidence in our ability to explain the past.

- When a surprising event happens, System 1 quickly adjusts our views of the world to accommodate it (see creating new norms).

- The problem is we usually forget the viewpoint we held before the event occurred. We don’t keep track of our failed predictions. This causes us to underestimate how surprised we were and overestimate our understanding at the time.

- For example, in 1972, participants in a study were asked to predict the outcome of a meeting between Nixon and Mao Zedong. Depending on whether they were right or wrong, respondents later misremembered (or changed) their original prediction when asked to re-report it.

- Hindsight bias influences how much we link the outcome of an event to decisions that were made. We associate bad outcomes with poor decisions because hindsight makes us think the event should have been able to be anticipated. This was a common bias in reactions to the CIA after the 9/11 attacks.

- Similarly, decision-making is not given enough credit for good outcomes. Our hindsight bias makes us believe that “everyone knew” an event would play out as it did. This is observed when people are asked about (and downplay) the role of CEOs in successful companies.

The Illusion of Validity

-

We often vastly overvalue the evidence at hand; discount the amount of evidence and its quality in favour of the better story, and follow the people we love and trust with no evidence in other cases.

-

The illusion of skill is maintained by powerful professional cultures.

-

Experts/pundits are rarely better (and often worse) than random chance, yet often believe at a much higher confidence level in their predictions.

-

The Illusion of Validity is caused by overconfidence in our ability to assess situations and predict outcomes.

-

People tend to believe that their skill, and System 1-based intuition, is better than blind luck. This is true even when faced with evidence to the contrary.

-

Many studies of stock market traders, for example, find the least active traders are the most successful. Decisions to buy or sell are often no more successful than random 50/50 choices. Despite this evidence, there exists a huge industry built around individuals touting their self-perceived ability to predict and beat the market.

-

Interestingly, groups that have some information tend to perform slightly better than pure chance when asked to make a forecast. Meanwhile, groups that have a lot of information tend to perform worse. This is because they become overconfident in themselves and the intuitions they believe they have developed.

-

Algorithms based on statistics are more accurate than the predictions of professionals in a field. But people are unlikely to trust formulas because they believe human intuitions are more important. Intuition may be more valuable in some extreme examples that lie outside a formula, but these cases are not very common.

Intuitions vs. Formulas

-

A number of studies have concluded that algorithms are better than expert judgement, or at least as good.

-

The research suggests a surprising conclusion: to maximize predictive accuracy, final decisions should be left to formulas, especially in low-validity environments.

-

More recent research went further: formulas that assign equal weights to all the predictors are often superior, because they are not affected by accidents of sampling.

-

In a memorable example, Dawes showed that marital stability is well predicted by a formula:

- frequency of lovemaking minus frequency of quarrels

-

The important conclusion from this research is that an algorithm that is constructed on the back of an envelope is often good enough to compete with an optimally weighted formula, and certainly good enough to outdo expert judgment.

-

Intuition can be useful, but only when applied systematically.

-

Interviewing

- To implement a good interview procedure:

- Select some traits required for success (six is a good number). Try to ensure they are independent.

- Make a list of questions for each trait, and think about how you will score it from 1-5 (what would warrant a 1, what would make a 5).

- Collect information as you go, assessing each trait in turn.

- Then add up the scores at the end.

- To implement a good interview procedure:

Expert Intuition: When Can We Trust It?

-

When can we trust intuition/judgements? The answer comes from the two basic conditions for acquiring a skill:

- an environment that is sufficiently regular to be predictable

- an opportunity to learn these regularities through prolonged practice

-

When both these conditions are satisfied, intuitions are likely to be skilled.

-

Whether professionals have a chance to develop intuitive expertise depends essentially on the quality and speed of feedback, as well as on sufficient opportunity to practice.

-

Among medical specialties, anesthesiologists benefit from good feedback, because the effects of their actions are likely to be quickly evident. In contrast, radiologists obtain little information about the accuracy of the diagnoses they make and about the pathologies they fail to detect. Anesthesiologists are therefore in a better position to develop useful intuitive skills.

-

Kahneman says some experts can develop their intuitions so their System 1 thinking becomes highly reliable. They have been exposed to enough variations in scenarios and their outcomes to intuitively know which course of action is likely to be best. In studies with firefighting teams, commanders were observed to use their intuition to select the best approach to fight a fire.

-

Not all fields yield experts that can enhance their intuitions, however. It needs immediate and unambiguous feedback, and the opportunity to practice in a regular environment. Expert intuition can be developed by chess players, for example, but not by political scientists.

The Outside View

-

The inside view: when we focus on our specific circumstances and search for evidence in our own experiences.

- Also: when you fail to account for unknown unknowns.

-

The outside view: when you take into account a proper reference class/base rate.

-

Planning fallacy: plans and forecasts that are unrealistically close to best-case scenarios could be improved by consulting the statistics of similar cases

-

Reference class forecasting: the treatment for the planning fallacy

-

The outside view is implemented by using a large database, which provides information on both plans and outcomes for hundreds of projects all over the world, and can be used to provide statistical information about the likely overruns of cost and time, and about the likely underperformance of projects of different types.

-

The forecasting method that Flyvbjerg applies is similar to the practices recommended for overcoming base-rate neglect:

- Identify an appropriate reference class (kitchen renovations, large railway projects, etc.).

- Obtain the statistics of the reference class (in terms of cost per mile of railway, or of the percentage by which expenditures exceeded budget). Use the statistics to generate a baseline prediction.

- Use specific information about the case to adjust the baseline prediction, if there are particular reasons to expect the optimistic bias to be more or less pronounced in this project than in others of the same type.

- Organizations face the challenge of controlling the tendency of executives competing for resources to present overly optimistic plans. A well-run organization will reward planners for precise execution and penalize them for failing to anticipate difficulties, and for failing to allow for difficulties that they could not have anticipated—the unknown unknowns.

-

Insider Blindness is a biased overconfidence that develops from within a team that is involved in completing a task.

-

This inside view is biased to be overconfident about the success of the task. It tends to underestimate the possibility of failure, in what is known as the ‘planning fallacy’.

-

For example, Kahneman describes a textbook that he and his colleagues started to write. They thought the project would take two years but an expert in curriculums found that similar projects took much longer. The team continued the project despite the outside view and the book took eight years to complete.

-

Insider blindness leads to assessments of difficulty based on the initial part of the project. This is usually the easiest part and is completed when motivation is highest. This “Inside View” can also better visualize best-case scenarios and does not want to predict that a project should be abandoned.

The Engine of Capitalism

-

Optimism bias: always viewing positive outcomes or angles of events

-

Danger: losing track of reality and underestimating the role of luck, as well as the risk involved.

-

To try and mitigate the optimism bias, you should a) be aware of likely biases and planning fallacies that can affect those who are predisposed to optimism, and,

-

Perform a premortem:

- The procedure is simple: when the organization has almost come to an important decision but has not formally committed itself, Klein proposes gathering for a brief session a group of individuals who are knowledgeable about the decision. The premise of the session is a short speech: “Imagine that we are a year into the future. We implemented the plan as it now exists. The outcome was a disaster. Please take 5 to 10 minutes to write a brief history of that disaster.”

-

An optimistic outlook gives people overconfidence in their ability to overcome obstacles.

-

Despite statistical evidence, people believe that they will beat the odds. This is often observed in business start-ups.

-

A Canadian inventor’s organization developed a rating system that could predict the success of inventions. No products with a D or E rating have ever become commercial. But almost half of the inventors who received these grades continued to invest in their projects.

-

Overconfidence and optimism encourage people to set unachievable goals and take more risks. Whilst it can be useful in maintaining commitment, it can cause people to overlook the basic facts of why a venture is unlikely to succeed.

-

These reasons often have nothing to do with the abilities of the people involved. For example, a hotel that failed with six previous owners still sells to a seventh owner. Despite evidence to the contrary, the new owners believe they are the game-changing factor rather than location and competition.

Choices/Prospect Theory

Utility Theory

-

Economic models used to be built on the assumption that people are logical, selfish, and stable. A dollar was a dollar no matter what the circumstances.

-

But Bernoulli proposed the ‘utility theory’. A dollar has a different value in different scenarios, because of psychological effects.

-

For example, ten dollars has more utility for someone who owns one hundred dollars than for someone who owns a million dollars. We make decisions based not only on the probability of an outcome but on how much utility we can gain or lose

-

Bernoulli’s Error: theory-induced blindness: once you have accepted a theory and used it as a tool in your thinking, it is extraordinarily difficult to notice its flaws

Prospect Theory

- It’s clear now that there are three cognitive features at the heart of prospect theory. They play an essential role in the evaluation of financial outcomes and are common to many automatic processes of perception, judgment, and emotion. They should be seen as operating characteristics of System 1.

- Evaluation is relative to a neutral reference point, which is sometimes referred to as an “adaptation level.”

- For financial outcomes, the usual reference point is the status quo, but it can also be the outcome that you expect, or perhaps the outcome to which you feel entitled, for example, the raise or bonus that your colleagues receive.

- Outcomes that are better than the reference points are gains. Below the reference point they are losses.

- A principle of diminishing sensitivity applies to both sensory dimensions and the evaluation of changes of wealth.

- The third principle is loss aversion. When directly compared or weighted against each other, losses loom larger than gains. This asymmetry between the power of positive and negative expectations or experiences has an evolutionary history. Organisms that treat threats as more urgent than opportunities have a better chance to survive and reproduce.

- The problem? Bernoulli’s theory cannot explain the outcomes of some economic, behavioral studies.

- Kahneman built on utility theory with Prospect theory – the value of money is influenced by biases from System 1 thinking.

- Prospect theory explains why economic decisions are based on changes in wealth, and that losses affect people more than gains.

Loss Aversion

-

The “loss aversion ratio” has been estimated in several experiments and is usually in the range of 1.5 to 2.5.

-

Loss aversion is the part of prospect theory that says people will prefer to avoid losses rather than seek gains.

-

It is observed in many different scenarios. A golfer will play for par rather than for birdies and contract negotiations stall to avoid one party making a concession. We judge companies as acting unfairly if they create a loss for the customer or employees to increase profits.

-

Prospect theory is based on the premise that people make judgments based on the pain that they feel from a loss. Since decisions are influenced by an emotional reaction, prospect theory and aversion loss are a result of System 1.

-

Loss aversion runs so deeply, it leads to the sunk cost fallacy. People will take further risks to try and recover from a large loss that has already happened. There is a fear of regret, that the decision to walk away will lock in a loss.

-

The brain responds quicker to bad words (war, crime) than happy words (peace, love).

-

If you are set to look for it, the asymmetric intensity of the motives to avoid losses and to achieve gains shows up almost everywhere. It is an ever-present feature of negotiations, especially of renegotiations of an existing contract, the typical situation in labor negotiations and in international discussions of trade or arms limitations. The existing terms define reference points, and a proposed change in any aspect of the agreement is inevitably viewed as a concession that one side makes to the other. Loss aversion creates an asymmetry that makes agreements difficult to reach. The concessions you make to me are my gains, but they are your losses; they cause you much more pain than they give me pleasure.

The Endowment Effect

-

Endowment effect: for certain goods, the status quo is preferred, particularly for goods that are not regularly traded or for goods intended “for use” - to be consumed or otherwise enjoyed.

-

Note: not present when owners view their goods as carriers of value for future exchanges.

-

The endowment effect is the increase in value that people apply to a product because they own it.

-

Prospect theory says that loss aversion is stronger than any potential gain. This applies even when there is a guaranteed profit to be made from selling an owned product. The profit needs to be enough to overcome the endowment effect, or the perception of loss, for people to sell.

The Fourfold Pattern

-

Whenever you form a global evaluation of a complex object—a car you may buy, your son-in-law, or an uncertain situation—you assign weights to its characteristics. This is simply a cumbersome way of saying that some characteristics influence your assessment more than others do.

-

The conclusion is straightforward: the decision weights that people assign to outcomes are not identical to the probabilities of these outcomes, contrary to the expectation principle. Improbable outcomes are overweighted—this is the possibility effect. Outcomes that are almost certain are underweighted relative to actual certainty.

-

When we looked at our choices for bad options, we quickly realized that we were just as risk seeking in the domain of losses as we were risk averse in the domain of gains.

-

Certainty effect: at high probabilities, we seek to avoid loss and therefore accept worse outcomes in exchange for certainty, and take high risk in exchange for possibility.

-

Possibility effect: at low probabilities, we seek a large gain despite risk, and avoid risk despite a poor outcome.

-

Indeed, we identified two reasons for this effect.

- First, there is diminishing sensitivity. The sure loss is very aversive because the reaction to a loss of $900 is more than 90% as intense as the reaction to a loss of $1,000.

- The second factor may be even more powerful: the decision weight that corresponds to a probability of 90% is only about 71, much lower than the probability.

- Many unfortunate human situations unfold in the top right cell. This is where people who face very bad options take desperate gambles, accepting a high probability of making things worse in exchange for a small hope of avoiding a large loss. Risk taking of this kind often turns manageable failures into disasters.

-

According to prospect theory, we overestimate highly improbable outcomes. This is because System 1 is drawn to the emotions associated with a highly unlucky or lucky outcome.

-

People become risk-averse to avoid an unlikely disappointment or seek out risk for the chance of an unlikely windfall.

-

For example, in scenarios with a 95% chance of winning, people will focus on the 5% chance of loss and choose a 100% win option with a lower value. They accept an unfavorable settlement.

-

In scenarios with a 5% chance of a large gain, like the lottery, people will choose this option over a sure win of a small amount. They reject a reasonable settlement.

-

Rare events, like plane crashes, also tend to be overestimated according to prospect theory. This is partly because the improbable outcome is overestimated. It is also because the chance of the event not happening is difficult to calculate. System 1 applies its ‘what you see is what you get’ bias.

- The probability of a rare event is most likely to be overestimated when the alternative is not fully specified.

- Emotion and vividness influence fluency, availability, and judgments of probability—and thus account for our excessive response to the few rare events that we do not ignore.

- Adding vivid details, salience and attention to a rare event will increase the weighting of an unlikely outcome.

- When this doesn’t occur, we tend to neglect the rare event

Context

-

In prospect theory, the context of how choices are presented affects our decision-making.

-

When people consider risk, they prefer to view choices one by one. The cumulative effect of decisions, which would give a better picture of overall risk, is more difficult to assess.

-

This is System 1’s tendency to frame questions into the one with the most cognitive ease, and the ‘what you see is what you get’ bias.

- For example, in a coin flip where you can lose $100 or win $200, you will win more money the more times you play, because the average outcome is to gain $50 each time.

- People that are asked if they would like to make five bets are more likely to accept than if people are asked on five separate occasions. They cannot consider the cumulative effect of many bets unless they are presented with it in a simple and obvious way.

-

The way that risk is presented can also provide a prime for a System 1 bias, especially if one option is associated with an emotional outcome like a loss.

- For example, people were given two options for a medication program for a disease. One can save a third of the people who contract a disease, the second has a two-thirds probability that no one can be saved. The options are the same but most people will select the first.

-

Risk Policies

-

There were two ways of construing decisions i and ii:

- narrow framing: a sequence of two simple decisions, considered separately

- broad framing: a single comprehensive decision, with four options

-

Broad framing was obviously superior in this case. Indeed, it will be superior (or at least not inferior) in every case in which several decisions are to be contemplated together.

-

Decision makers who are prone to narrow framing construct a preference every time they face a risky choice. They would do better by having a risk policy that they routinely apply whenever a relevant problem arises. Familiar examples of risk policies are “always take the highest possible deductible when purchasing insurance” and “never buy extended warranties.” A risk policy is a broad frame.

-

Keeping Score

-

Agency problem: when the incentives of an agent are in conflict with the objectives of a larger group, such as when a manager continues investing in a project because he has backed it, when it’s in the firms best interest to cancel it.

-

Sunk-cost fallacy: the decision to invest additional resources in a losing account, when better investments are available.

-

Disposition effect: the preference to end something on a positive, seen in investment when there is a much higher preference to sell winners and “end positive” than sell losers.

-

An instance of narrow framing.

-

Regret

- People expect to have stronger emotional reactions (including regret) to an outcome produced by action than to the same outcome when it is produced by inaction.

- To inoculate against regret: be explicit about your anticipation of it, and consider it when making decisions. Also try and preclude hindsight bias (document your decision-making process).

- Also know that people generally anticipate more regret than they will actually experience.

-

-

Reversals

- You should make sure to keep a broad frame when evaluating something; seeing cases in isolation is more likely to lead to a System 1 reaction.

-

Frames and Reality

- The framing of something influences the outcome to a great degree.

- For example, your moral feelings are attached to frames, to descriptions of reality rather than to reality itself.

- Another example: the best single predictor of whether or not people will donate their organs is the designation of the default option that will be adopted without having to check the box.

evaluating our experiences

-

System 1 creates problems when we evaluate our experiences, including our happiness.

-

Kahneman states that we have two selves. The ‘experience self’ evaluates outcomes as they happen. The ‘remembering self’ evaluates the outcome after the event. The remembering self tends to have more power in decision-making.

-

The remembering self uses the peak-end rule, placing more importance on the end of an experience than any other part. It also suffers duration neglect, where the length of an experience is disregarded.

-

In a study, people were given the option of two painful procedures. One lasts eight minutes and gradually increases in pain until the end. The second lasts twenty-four minutes and has the same intensity of pain but in the middle. Most people will choose the second procedure.

-

The remembering self will also choose options that value the memory of an experience, more than the experience itself. Likewise, it will choose to suffer pain if that pain can be erased from memory.

-

Asking people about overall life satisfaction is an important measure in many studies. But System 1 tends to replace this difficult question with an easier one. The remembering self answers about how they have felt recently.

-

Kahneman proposes a better methodology for prompting the experience self. He has conducted studies that ask people to reconstruct their previous day. This gives a better measure of well-being and happiness and has resulted in better insights into how this is affected.

-

Two Selves

- Peak-end rule: The global retrospective rating was well predicted by the average of the level of pain reported at the worst moment of the experience and at its end.

- We tend to overrate the end of an experience when remembering the whole.

- Duration neglect: The duration of the procedure had no effect whatsoever on the ratings of total pain.

- Generally: we tend to ignore the duration of an event when evaluating an experience.

- Confusing experience with the memory of it is a compelling cognitive illusion—and it is the substitution that makes us believe a past experience can be ruined.

-

Experienced Well-Being

- One way to improve experience is to shift from passive leisure (TV watching) to active leisure, including socializing and exercising.

- The second-best predictor of feelings of a day is whether a person did or did not have contacts with friends or relatives.

- It is only a slight exaggeration to say that happiness is the experience of spending time with people you love and who love you.

- Can money buy happiness? Being poor makes one miserable, being rich may enhance one’s life satisfaction, but does not (on average) improve experienced well-being.

- Severe poverty amplifies the effect of other misfortunes of life.

- The satiation level beyond which experienced well-being no longer increases was a household income of about $75,000 in high-cost areas (it could be less in areas where the cost of living is lower). The average increase of experienced well-being associated with incomes beyond that level was precisely zero.

-

Thinking About Life

-

Experienced well-being is on average unaffected by marriage, not because marriage makes no difference to happiness but because it changes some aspects of life for the better and others for the worse (how one’s time is spent).

-

One reason for the low correlations between individuals’ circumstances and their satisfaction with life is that both experienced happiness and life satisfaction are largely determined by the genetics of temperament. A disposition for well-being is as heritable as height or intelligence, as demonstrated by studies of twins separated at birth.

-

The importance that people attached to income at age 18 also anticipated their satisfaction with their income as adults.

-

The people who wanted money and got it were significantly more satisfied than average; those who wanted money and didn’t get it were significantly more dissatisfied. The same principle applies to other goals—one recipe for a dissatisfied adulthood is setting goals that are especially difficult to attain.

-

Measured by life satisfaction 20 years later, the least promising goal that a young person could have was “becoming accomplished in a performing art.”

-

The focusing illusion:

-

Nothing in life is as important as you think it is when you are thinking about it.

-

Miswanting: bad choices that arise from errors of affective forecasting; common example is the focusing illusion causing us overweight the effect of purchases on our future well-being.

-

The community of knowledge

- Fernbach and Sloman suggests that we’re successful as individuals and communities for several reasons. Firstly, we live with knowledge around us. This includes our bodies, the environment and other people. Secondly, individuals within a community can divide cognitive labor and specialise. Thirdly, individuals are able to skills and knowledge. These factors enable more effective coordination and collaboration within and between communities.

Thinking as collective action

-

Unlike computers, we are unable to hold vast amounts of information. We select only the most useful or available information to guide our decisions. Our limited capacity means we rely on a community of knowledge within our minds, the environment and other people to function. To Fernbach and Sloman, human thought is a product of the community, where people are like bees and society our beehive. Our intelligence is contained in the collective mind and not the individual brain.

-

To emphasise the point, our knowledge as individuals are intertwined with the knowledge of others. Since our beliefs and attitudes are shaped by communities, there becomes a tendency for us to associate with one prescription or another. We tend to let the group think for us because it is difficult to reject the opinions of our peers. As such, we don’t always evaluate the merit of every belief or attitude shared.

-

It takes a lot of expertise to understand the complexities of an argument. Society would be less polarised if we understood the communal nature of knowledge better. It helps to know where the limitations of ourselves and others begin and end. This can help us to determine our beliefs, values and biases with more perspective.

The knowledge illusion

- Individuals cannot know or master everything. Instead, we rely on abstract knowledge to make decisions. Sometimes this includes drawing upon vague and under-analysed associations to provide high-level links between objects.

Illusion of understanding

-

Since our brains are not equipped to understand every event or discipline, we apply prior generalisations to new situations to act and make decisions. Our capacity to function in new environments depends on the regularities of the world and our understanding of these regularities.

-

People are typically more ignorant than they think they are (much like the Dunning-Kruger effect). This illusion of understanding exists because we often fail to draw a distinction between the knowledge of the individual and the community. This can lead to overconfidence and not knowing that we do not know.

Illusion of explanatory depth

-

Our illusion of understanding often hides how shallow our understanding of causal mechanisms are across subjects. The authors give a striking example in their three-part questionnaire. To paraphrase them – For any everyday object (e.g. zipper, bicycle, kettle and toilet), ask yourself or someone these three questions in order:

- On a scale of 1-10, how well do you understand how it works?

- Can you explain to us in as much detail as possible about how it works?

- Now, on a scale of 1-10, how well do you understand how it works?

-

This assessment can show our preconceived illusion of explanatory depth. Our self-assessment scores in the third question is often lower than the self-assessment score of the first. Like the illusion of knowledge, we can also suffer from an illusion of comprehension. We sometimes confuse understanding with recognition or familiarity.

Evolution’s endowment

- The human mind evolved abilities to take actions to better enable our survival. Remembering vast amounts of information was not helpful to our evolution. As our brains developed in complexity, we got better at responding to more abstract environmental cues and new situations. Furthermore, unnecessary details are counterproductive to effective and efficient action if a broad understanding suffices. This is why our attention and memory systems are sometimes limited and fallible. We may have evolved a different set of logic if it was conducive to our evolution and survival as a species.

First we overestimate, next we ignore

-

Humans use causal logic to reach conclusions and project into the future. We share similarities with computers in that we undertake complex tasks by combining simpler sets of skills and knowledge together. However, the illusion of explanatory depth means we often overestimate the extent and quality of our causal reasoning.

-

We acquire information slowly and spend only a small fraction of our lives deliberating. Doing otherwise would leave us unable to handle systems that are too complex, chaotic or fractal in nature. The illusion of understanding means we tend manage complexity by ignoring it. Likewise, we ignore alternative explanations when we’re unable to retrofit it into our pre-existing model of understanding.

Hierarchies of thought and processes

-

Fernbach and Sloman highlight how we construct our models of the world from a tiny set of observations. This is possible because our world usually conforms to generally consistent principles. We can also think of the brain as one part of a larger processing system. It combines with the body and the external environment (an outside memory store) to remember, reason and interact.

-

Complex behaviours emerge when individual systems can interact or coordinate with each other. Multiple cognitive systems that work together may give rise to a group intelligence that exceeds the capability of any one individual. This is the case with bees, ants and humans. The growth in our collective intelligence for example can be attributed to the growing size and complexity of our social groups.

-

The human brain didn’t evolve to store information and the world is extremely complex.

- Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the predominant theory among cognitive scientists was that the brain was basically a sort of organic computer.

- in the 1980s, a pioneering cognitive scientist named Thomas Landauer turned this model on its head. Landauer figured that, if the brain’s main job was to carry out computer-like functions – things like storing and processing information – then it would be informative to estimate the size of human knowledge in computational terms. Hi experiments proves an important point: our brains, unlike computers, are not designed to function primarily as repositories of knowledge because there is, quite simply, too much of it. The world is an infinitely complex place. For example, did you know that there’s not a person alive who understands all there is to know about modern airplanes? They’re simply far too complicated, and understanding them completely requires a team of specialists.

- This raises yet another tricky question: what did our brains evolve to do?

-

The human brain evolved for action, and diagnostic reasoning may be what differentiates us from other animals.

- What’s the difference between a Venus flytrap and a jellyfish? Sure, one lives on land, traps bugs and is capable of photosynthesis, while the other floats around in the water, has tentacles and looks bizarre – but what makes them fundamentally different?

- Well, one of them is capable of action, and the other is not. This difference is profound, because the ability of organisms to act on and interact with their environment is what led to the evolution of the brain.

- the more neurons an animal has, the more complex the actions it’s capable of.

- Humans possess billions of neurons. We can travel to space and compose concertos. But we evolved such complex brains for the same reason that jellyfish evolved their rudimentary system of neurons: to enable effective action.

- So if all brains evolved to assist action, what (besides billions more neurons) differentiates humans from other, less neuronally endowed animals? Well, one answer might be our ability to engage in causal reasoning.

- Not only can we reason forward, predicting how today’s actions may shape tomorrow’s events; we can also reason backward, explaining how today’s affairs may have been caused by yesterday’s actions. This is called diagnostic reasoning, and although we’re by no means perfect at it, our ability to do it is arguably what sets us apart from other sentient creatures.

- What’s the difference between a Venus flytrap and a jellyfish? Sure, one lives on land, traps bugs and is capable of photosynthesis, while the other floats around in the water, has tentacles and looks bizarre – but what makes them fundamentally different?

-

When trying to answer a question or solve a problem, people engage in one of two kinds of reasoning. Either they use intuition, or they use deliberation.

- We use intuition all the time because it’s sufficient for day-to-day purposes. But when things get more complicated – when we have to draw a bicycle rather than just ride it, for example – intuition breaks down.

- if you paused before shouting out the answer and were able to work out the correct answer, then you might be one of those rare creatures: a person who favors deliberation over intuition.

- Such people are highly reflective and, unlike most of us, yearn for detail. They are also less likely to exhibit any illusion of explanatory depth. It’s not that they know more; it’s that they’re aware of how little they know. They’re probably no better than most people at drawing a bicycle, but they know that they can’t do it.

- Intuitions are subjective – they are yours alone. Deliberations, on the other hand, require engagement with a community of fellow knowledge possessors. Even if you deliberate in solitude, you’ll converse with yourself as though talking to someone else. This is just one of the many ways that we externalize internal thought processes to assist cognition.

-

We think with our bodies and the world around us.

- You may not be a philosopher (most people aren’t), but you’re probably familiar with René Descartes’s famous words, Cogito, ergo sum: “I think, therefore I am.” Descartes believed that our ability to think, not our physical body, is what determines our identity, and that engaging in thought is distinct from physical activities.

- This Cartesian emphasis on the preeminence of thought contributed to a faulty assumption made by early cognitive scientists, namely that thought is carried out in the mind alone.

- As we learn more about the mind, however, it appears that, when thinking, we also employ our bodies and the world around us, using them as tools to assist our everyday calculations and cogitations.

- In general, we assume that the world will continue to behave as it always has. We assume that the sun will rise and that what goes up must come down. This enables us to store a great deal of information in the world. You don’t need to remember every particular detail of your living room because, in order to remind yourself what’s there, you only need to take a look.

- We also use the world to help us make complex computations, rather than conducting them in our head.

- We also use our bodies and physical actions to aid thought. This is called embodiment, and its proponents assert that thought is not an entirely abstract process that plays out inside your head.