civilization

-

One that stood out for me is the idea that there are three major breakthroughs throughout human history. And each was prompted initially by geographical factors — purely incidental and arbitrary you could say, which gave certain areas of the world a leg-up in achieving unprecedented development and subsequently more advanced form of civilization as measured by Morris’ four metrics of human society. However, since we are instinctive animals produced by millions of years of evolution, some of the primal desires are coded in our DNA. That is, by design, we humans gravitate towards some sort of equality; more specifically, “equity in outcomes on emotional grounds and fairness in opportunities on rational basis”. Thus, when the advancement finally spreads to other parts of the world, whether by design or by chance, the inhabitants of those places would naturally want to adapt (if they in fact see it as such). And if they don’t, as exemplified by the Chinese Qing Dynasty refusing to concede to Western “tricks and gimmicks” (what we now call science and technology), there is a dear price to pay. But of course, eventually history will power through any willful ignorance and blind denial, and incorporate them into the process one way or another, no matter how “central” they think they are (Note: China, or Zhong Guo, essentially means “the central country” in Chinese). To adapt or to perish, it’s a question.

-

The book starts out by covering a broad topic: human civilization. From attempting to understand our shared two-million-year-old past, Lu hopes to gain some foresight as to what awaits us in our future. A few books he referenced are also a few of my favorites on the topic:

- Jared Diamond — Guns, Germs, and Steel

- Yuval Noah Harari — Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

- Ian Morris — Why the West Rules — For Now

- E. O. Wilson — The Social Conquest of Earth

- From these books, Lu introduces our civilization in three stages:

- Civilization 1.0 — Hunter-Gatherer Age

- Civilization 2.0 — Agricultural Age

- Civilization 3.0 — Industrial/Technological Age (modern civilization)

-

Jared Diamond famously stated that the rise of European and Asian powers in the Agricultural Age was predetermined by geography and climate. Out of all the edible grains in the world, only five (wheat, corn, rice, barley and sorghum) stood out as the main sources of energy consumption for humans. When it comes to animal husbandry, out of 148 mammals on earth, we were only able to domesticate 14 types of animals. In addition, out of the five most important domesticated animals today (sheep, goats, cows, pigs and horses), four could trace their origins to Southwest Asia. Naturally, where these grains grow and harvest the best and where these animals were able to survive would also determine where humans flourished.

-

The fundamental difference between civilizations 2.0 and 3.0 is that 2.0 operates under a system characterized by shortages. That is, the growth of a society is limited by its agricultural output, which is in turn dictated by natural forces such as seasons, climate and photosynthesis. Once a society grows to a certain size, it inevitably falls into the Malthusian trap, where a significant amount of the population has to die out in order for the society to revert back to a point of equilibrium. Sounds incredibly cruel and reminiscent of Marvel’s almighty, mission-driven, almost reasonable villain, Thanos, who decided that half of randomly selected humans must perish (like, literally turning into ashes) in order to save the Earth and so he set out to do just that. Well, guess what? Civilization 3.0 powered by free market and technological advancements and capable of unlimited growth, come to rescue. I know, I know. We also run a greater risk of perishing altogether thanks to our unbounded power to destroy, you smart son of a gun. Can we just play along for now? Anyhow, the West boarded the first 3.0 train this time around and developed so quickly like no one had seen before. In the proceeding centuries, several Asian countries followed, first Japan, then South Korea, Singapore, now China. They all showed likewise pattern regardless of their political systems: one-party, two-party or multi-party rule; direct or indirect democracy; capitalism or communism — different paths, same destination that is unlimited, explosive, constant economic growth and a civilization of materialistic abundance.

-

Most of the book’s focus on civilization, however, revolves around “civilization 3.0” — industrial revolution, technological revolution and modernization. Lu starts out the discussion at Axial Age, a period between 8th to the 3rd century BCE, named by German philosopher Carl Jaspers. During these years, humans “leveled up” their thinking and understanding of philosophy and religion and achieved cultural and spiritual awakening. The thinkers during these years still influences the way we think today:

- In China, philosophers like Confucius, LaoZi, and Mozi along with the Hundred School of Thoughts appeared during the Warring States.

- In Nepal and India, we witnessed the birth of the Buddha, hinduism, buddhism, along with nihilism and scepticism.

- In the Middle East, prophets started recording their teachings and thoughts, forming the basis for modern Catholic and Islamic faith.

- In Greece and western Europe, Homer and Plato became immensely popular, influencing Christianity and even Renaissance that came centuries afterwards.

-

Jaspers noted in his book Origin and Goal of History that these great thinkers shared many similarities. They all existed in a period of great struggle and uncertainty, with governments that were autocratic and corrupt. Their audiences were mainly the lowest class of citizens, minorities, and the repressed. Although their teachings were often revolutionary, they weren’t actual revolutionists. The intent was often simpler: to understand the meaning of life and what makes a society fairer and better.

-

Lu’s interpretation here is

- human nature dictates that emotionally we pursue the equality of results (resources and money) and rationally the equality of opportunity

-

I think this is a very important notion. By linking human nature directly with the pursuit of equality and fairness, he is able to explain to his readers that the following are the the greatest innovations of human civilization:

- Free market economy

- Ke Ju (科举制, civil service examination system based on meritocracy)

-

Ke Ju (科举制) came first. The Chinese imperial examination system (~220 B.c.) was used to recruit talent from all over the country to make up its governing body. It took both attitude and aptitude into consideration, and promised a fair, open, and transparent chance for all, regardless of family background or upbringing like the systems prior. Because of this universal recruiting method, China was able to incentivize talent to participate in government and politics, provide upward mobility for its citizens, and to economically lead the world for more than ten centuries afterwards.

-

Lying beneath the seemly mundane surface are two protruding factors that likely affected the trajectory of either societies as far as I can see based on what I learned from the book. First of all, despite of its tremendous benefits, Keju has its flaws and is far from enough to sustain China’s evergrowing population and advancing society. It grants political privileges to whomever willing to and capable of passing a series of examinations, that promised a pathway for anyone (theoretically) to rise to political prominence. But! Ultimately there’s a limit to how far one can go. That is, the throne. And given the position of the highest ruler can only be inherited, not earned, it is up to that one individual and his (yes, the vast majority, if not all, of them were men) select trustees, often related to him by blood or through marriage as well, to determine what happens to the entire empire — the largest on earth at the time. It is their wisdom, character, knowledge and ability the whole country relies upon for peace, survival and continuation. If that’s not a crapshoot I don’t know what is.

-

Keju was also limited in its rigidity, though technically it didn’t have to be. Ming Dynasty is infamous for its turning its bureaucrat selection system into a “word prison” or, perhaps more fittingly, “hell of words”. The empire’s gradual loss of toleration in free thoughts and original ideas, and eventually loss of interest in assessing candidates on what could be practical or functional in serving the empire, which is what the Keju system was designed to do, probably predated the rise of Ming Tai Zu (first Emperor of Ming Dynasty) by many centuries. And the reason behind that, in hindsight at least, is pretty clear. Whatever the system was selecting, it was meant to serve the ruler, the throne, the product of the crapshoot that may or may not (and most likely not) care about the millions of people outside of his fortress, whom supposedly were born to serve him, not the other way around.

-

Additionally, there is no mentioning of economic meritocracy alongside its political counterpart. It is well-known that businessmen are at the very bottom in terms of the traditional Chinese hierarchy of noble career choices for the plebs. I’m referring to the “bureaucrats, peasants, craftsmen, and businessmen” (in descending order)

-

Fast forward to the 1200s and Magna Carta, then 1689 and the Bill of Rights, Europeans slowly started taking power away from the crown and into the hands of the “people” (represented by the wealthy). In Britain, these important policy changes marked the transition to limited constitutional monarchy, arguably equally significantly, the first “commercial constitutional state” — one where the House of Commons represents the interests of businessmen and property owners. It sets Britain up to become the indisputable commercial hub of the 17th century.

-

It was also at this critical juncture in history, a transcontinental trade network was quietly being established in the Atlantic, starting with the discovery of the Americas in end of the 15th century. The Transatlantic Trade Network was the first decentralized market ecosystem not controlled by a single nation state and an experiment of true free capitalism. The pros and cons of such a bold experiment are still being felt today, from social issues like racism in the Americas to economic ones like the impact of globalization and monopolies.

-

Lu also reiterates the importance of free market economy by pointing out that 1776 was a special year, where a series of important events happened that officially transitioned the western world into civilization 3.0:

- Adam Smith’s Wealth of the Nation, setting the foundation of a free market economy.

- American Founding Father’s Declaration of Independence, creating rule of law and centuries of prosperity in a new nation.

- The Watt steam engine is commercialized and the design is sold to Carron Company ironworks, officially kicking off the industrial revolution.

-

Adam Smith is well known today as the father of economics and modern capitalism. Almost weekly on CNBC, people still reference the “invisible hand” of the market, a concept Adam Smith coined to describe the automatic pricing mechanism in an economy. Adam Smith’s concept of the “invisible hand” was less biased than modern interpretations. Today, the free market ideology largely uses it to justify that while unfettered by the intervention of government regulations, society would flourish organically due to the competition that it naturally fosters. A smaller government should always function better because it leaves room for private ownership and partnerships, and creates as little resistance to the “invisible hand” as possible. Greed of the consumers that demand the best product at the lowest price would drive the market to a point of absolute efficiency.

-

The Declaration of Independence and the steam engine need no further introduction. Lu highlights the importance of rule of law and technological achievements in the modernization of the western world, the former surrendered by the monarch, and the latter made possible by free market competition.

Monopolies and the Free Market

- Monopolies took many forms throughout human history — from forms of governments like city states and nation states to joint stock companies like the EICs (East India Company). There seems to be a natural tendency for humans to form these all powerful entities in order to achieve greater degree of control. Lu proposes another way to look at monopoly that I never considered before: a global marketplace being a monopoly, from which he summarizes the Iron Law for the Civilization 3.0:

一个自由竞争的市场就是一个不断自我进化、自我进步、自我完善的机制,现代科技的介入使得这一过程异常迅猛。这样在相互竞争的不同市场之间,最大的市场最终会成为唯一的市场,任何人、企业、社会、国家,离开这个最大的市场之后就会不断落后,并最终被迫加入。一个国家增加实力最好的方法是放弃自己的关税壁垒,加入到这个全球最大的国际自由市场体系里去;反之,闭关锁国就会导致相对落后。这就是3.0文明的铁律。

The only way to survive is to join in on the biggest global free market. Any entity attempting to create barrier (ie raise tariffs), break away to create smaller regional markets, will eventually become obsolete and will be forced to rejoin the monopoly later.

-

According to Lu, humans fought for control over land in civilization 2.0 (Agricultural Age). In civilization 3.0, we fight for the control over the global market monopoly. The size of an economy’s market determines its longevity. After WWII, United States gave up a lot of land it captured. Instead, it started forming a series of global organizations, such as the United Nations, World Bank, IMF, and Bretton Woods. These international organizations essentially set up a global marketplace. The U.S. also fought hard to hold on to the rights of creating, changing, and enforcing the rules of this marketplace. Initiatives like the Marshall Plan and security treaties with Japan and Korea can also be seen as such efforts. The establishment of a global marketplace also greatly accelerated the effect of globalization.

-

Globalization is a very unique phenomenon in human history. A completely global free market economy we have today really only existed for 30 years or so, since the end of the Cold War in 1989. During the Cold War, we had two major economic sphere of influences. Both superpowers used trade sanctions, embargoes, and blockage of financial access as means of economic warfare. Eventually, only one market prevailed, and we are living in a world order created by that monopoly today: dollar is the dominant world currency, english is the world’s language, Hollywood is the world’s culture, and the U.S. military is the world’s police force.

China: Past and Future

Economy

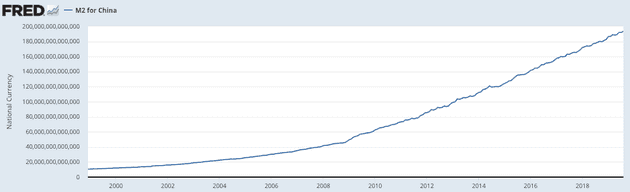

- To discuss the Chinese economy, it’s hard not to talk about John Maynard Keynes. The Keynesian school of economics largely came out of the Great Depression in the 1930s. Contrast to Adam Smith, Kaynes believed that the “visible hand” of the government can help stabilizing the economy through manufactured demand and centralized workforce, thus pulling the U.S. out of economic depressions via increased governmental debt and expenditure. MMT (Modern Monetary Theory) can be seen as an extension of Keynesian Economics. And China has been riding the quasi-MMT train for quite a while

-

Chinese businesses deeply understand the meaning of this “visible hand” from its government. For thousands of years, the Chinese government had always managed its economy, effectively creating a repeated business cycle of opening, prosperity, intervention, lockdown, and reopening. In the past 40 years after Deng, the Chinese economy entered another “opening and prosperity” phase.

-

Lu noted that even though the exponential growth of China has been impressive, the trend is unlikely to continue unless certain policies are significantly altered going forward. When an economy is transitioning from “developing” to “developed,” it’s relatively easy to follow the path that others have laid before and copy as much as they can. This playbook isn’t new either — almost all Asian countries (Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Thailand to a lesser extent) rose up in the 90s with the help of central planning. A famous account of Japanese Central Bank’s aggressive policies in the 80s and 90s, such as window guidance, can be found in Richard Werner’s book Princes of the Yen.

-

During this period of prosperity, the Chinese government relied heavily on exporting manufacturing (cheap labor) and smart/effective central planning. They guided investments and capital domestically and internationally into important infrastructure projects and achieved unprecedented progress in a short period of time. However, as China surpasses the U.S. and became the number one export nation in 2019, it now needs to turn inwards to seek additional growth. At the same time, as investments continue to creep up and make up almost half of China’s GDP, the government will be forced to let go of some of its control on the economy, and give more leniency to the “invisible hand” of the free market. The takeaway here is simple: a centrally planned economy is a short term, opportunistic band-aid solution; it can never be as effective as free market economy during a time of uncertainty — when there’s no more path laid out in front by others, governments tend to react slower and are at a position of disadvantage. Hence, Lu lays out his first prediction of China’s future: it has to transition from a government-controlled economy to a government-assisted free economy.

-

To me, this prediction seems overly optimistic, though still quite fun to think about. As China transforms itself into a domestically service oriented economy, consumers will likely demand a more open and transparent society (or at least a fairer financial market). State-owned enterprises (国企) should not be able to borrow the same way they do today, with basically no obligation to repay debt without fear for bankruptcy. Any citizen should be able to participate in the industries that are traditionally limited to certain state-backed companies (finance, energy, or even defense). Financial markets will have to be regulated to attract more institutional capital and stability. Pension systems and social welfare can then be more privatized and therefore not solely be the burden of the central government.

-

Another thought-provoking takeaway from the later part of the book is central government’s place in a nation’s economy. After all, “free market is by no means free”, Li observes. Indeed, to ensure the proper functioning of a large free market is no small undertaking. It requires tremendous amount of funds and effort that no individual company or industry could or, I would argue, should provide. That said, Li agrees that governments have different roles to play depending on a country’s stage of economic development. There are two turning points marking three stages of economic development in a post-agricultural society. The first being the Lewis Turning Point raised by English economist W. Arthur Lewis. Before the arrival of this turning point, Lewis proposes, capital has absolute dominating power over labor. Labor skills are low and often in high supply thanks to former agricultural workers pouring into cities for higher-paying modern jobs. Therefore, wages are uniformly low, so are unit price and profit margin. At this stage saving may be citizens’ main goal; thus, it makes sense for government to indirectly participate in the economy — borrowing money from the savers and invest it into the economy either by lending to sprouting businesses or by establishing state-owned enterprises to build and strengthen infrastructure.

-

It would be nice to see all economies hang out in this sweet spot till the end of time; however, history teaches us that nothing lasts. Increasingly we see developed countries, burdened by low birth rate and aging population, having low or negative interest rates. Fiscal policy that used to work like magic for the longest time stopped working; people became more and more reluctant to spend no matter how low interest rates are. This phenomenon was brought to spotlight by economist Richard Koo, observing the lack of vitality in Japanese economy since the 1990s. Once a society arrives at this stage, it would again make sense for the “Big Brother” to take action and assume an active role in the economy as in stage I.

-

Reality, of course, is not as clear-cut. And governments around the world are generally large, cumbersome political machines characterized by bureaucracy, inertia and latency in execution. The size of a country matters, and so do culture and ingrained beliefs and perception about the government’s role. For countries like China, where for centuries central government has always taken on an active role on the economic stage, it may be hard to convince policy makers at various levels to chill out a little and loosen their grip on the economy. However, with China approaching (some may say having passed) the Lewis Turning Point, this becomes increasingly important and should be done sooner rather than later. I’m fairly hopeful it will happen though. After all, thanks to modern-day version of Keju, China’s got the most capable and efficient bunch of bureaucrats working towards its renaissance.

-

Conversely, countries heading towards or perhaps had already crossed the second turning point, given their long-running democratic tradition, may have a hard time adjusting to the fact that even the most powerful machine — the free market — may need an oil change. This can finally become reality in the US with Trump disgracefully shooed out of the White House. Will American government show as much vigor and determination as T.R.’s administration did back in the Great Depression? Will Americans, increasingly radicalized and divided, be on board? I sure hope so.

Culture

-

The author focused on the issue of culture and tradition abandonment by most Chinese living in China today. He believes that a country’s culture is “consisted of centuries of habits and traditions, religions and history.” It’s an all-encompassing belief and faith system that cannot be replaced, it’s “deep in the bones.” Through cultural revolution, China had attempted to erase just that. The author predicts that in the near future, we will see a movement of Chinese Culture Renaissance. To him, Chinese people must learn to embrace their own culture again before moving into the civilization 3.0

-

On the topic of governance and politics, Lu briefly covered three major schools of thought: Ru(儒) or Confucianism, Dao(道) or Taoism, Fa(法) or Legalism. In Chinese politics, it is often believed that achieving a balance among the three can guarantee the success of a dynasty or ruler. Lu believes another school of thought, Mo(墨) or Mohism should play a more pivotal role as China enters its modernization phase. Mohism emphasizes universal love, social order, sharing, and honoring the worthy. Equality for all is also a major theme in Mohism, which might be why it did not gain much popularity during the dynastic rules of China.

-

Lu believes that as society advances, the balance between individualism vs. collectivism will inevitably tilt in favor of the former. In an advance economy, individuals should dictate terms and politics and become the entirety of politics (by the people and for the people). Therefore, individual rights such as freedom, safety, and private ownership of properties must be protected, and should be the only function of a government.

-

To Lu, a modernization of the Chinese culture is just as crucial as the modernization of the Chinese economy. An example he gave was the idea of traditional cardinal human relations, called Wu Lun (五伦八德). It describes five different sets of relationships and defines the proper societal behavior depends on one’s role in such relationships:

中国传统文化中的人际关系有五伦,君臣、父子、夫妻、朋友、长幼。五伦的文化中,各有自己的道德准则,父子有亲,君臣有义,夫妇有别,长幼有序,朋友有信。五伦基本讲的是熟人之间的关系,所以中国的文化是人情文化。

Between the government and citizens (“ruler and subjects”): the government must effectively and intelligently protect the safety of the people and their property, this being the equivalent of the obligation in the olden days of rulers to be “competent rulers”, while the citizens must pay taxes to the government, obey the government’s laws, serve with loyalty and the utmost diligence when recruited or conscripted by by the government, and when appropriate give opinions to the government or try to dissuade the government, these being the equivalent of the obligation in the olden days of subjects to be loyal;

Between parents and offspring: parents must raise and educate the offspring, while the offspring must carry out xiao (“be good to parents”) and support and care for aged, weak parents;

Between husband and wife: both must be of one heart and mind, and help each other to together build a family life where both the next generation is raised and the previous generation is cared for;

Among siblings: older siblings must be kind and helpful to the younger ones, the younger siblings must be respectful to the older ones, and all siblings must help each other;

Among friends: friends must help each other, especially with mutual encouragement, mutual advice, and dissuasion from what is wrong.

- Lu sees a much needed amendment to these five types of relationships as China enters the modern age — a defined way to treat strangers. He believes that by only having these five types of relationships, Chinese society became too much of a GuanXi-oriented society, where GuanXi is often considered above the law. To Lu, rule of law is what defines that relationship among strangers in a shared society with shared ethics, and is crucial to its social order and stability.

更严重的是,缺乏陌生人之间的道德准则,是导致商业诚信缺失的重要原因之一,而诚信恰是自由市场经济的润滑剂

More seriously, the lack of ethical standards among strangers is one of the important reasons for the lack of business integrity, and integrity is the lubricant of a free market economy.

Recap: Four Big Ideas in Value Investing

-

We can sum up the idea of value investing into the following four points:

- Mr. Market

- Stock as a piece of a business

- Margin of safety

- Circle of competence

-

The first three can be traced back to Ben Graham’s book The Intelligent Investor, the last one was added by his disciples Buffett and Munger. These concepts are so comprehendible that unfortunately, they are often substantially overlooked when people first started investing.

-

It’s just that the absence of an objectively sound evaluation system makes the stock market seem to me awfully like a fertile ground for costly, misleading information if not outright fraud. This is where the value of value investors come in, Li argues. With the right tools and intention on their side, value investors are the true price setters of the market and the only reason why the stock exchange around the world are more than a casino.

-

After all, as Li puts it, that’s what the stock market is there for: to get everyday people’s savings into the right hands in order to raise capital for promising businesses, generate wealth for stakeholders, and invigorate the economy. They search for worthwhile companies like a treasure hunter, and learn about anything related or unrelated to their targets along the way. In Li Lu’s words, ideally a value investor is more of researcher than an investor. Once they confirm their “kill”, sometimes after decades of studying and contemplating, they pull the trigger with unflinching conviction and hold it for a long time. “That’s how I sleep tight at night unlike some of my colleagues”, he reckons. As cool as it may sound, I can’t help but notice the “conscientious bankers” never made it in Hollywood. Too bad.

Mr. Market Analogy

-

The Mr. Market analogy is meant to teach us how to differentiate investing and speculating. One can think of the Mr. Market as someone who is extreme, moody, and without much thoughts. The first thing he does every morning is to shout out the latest prices. He does this continuously throughout the day. When he’s optimistic about the future, he acts like an excited auctioneer and frequently adds more to the prices; when he’s depressed, he drastically lowers the prices.

-

It’s easy to see Mr Market is a very irrational person. The market operates very much on the two extremes of the spectrum, continuously swinging from peaks to valleys and back again. Most people choose the path of speculation and call themselves traders. It’s the most obvious path, a path that can provide quick riches and fast cash. Most traders attempt to time the market, believing that they are a lot smarter and have a lot more insight than the rest of the traders. Some get lucky and make a lot of money in a short period of time. They feel validated, feeding into their own self-fulfilling prophecy, and believing that they are indeed gods of the market.

-

Value investing fundamentally discourages speculation, and the reasons are simple:

- One can think of market index (ie total stock market index) as a zero sum game, where its value is equivalent to the sum of all investments from both investors and speculators. If the index rises at the same rate as the output from all investors, then the total output of speculators must be 0.

- Speculators cannot have long term performance due to the point above. If they do better in the short term, what they are doing can be seen as some form of legalized front-running or the murky area of information exploitation or insider information.

-

The market is also a good judge of character.

市场是一个发现人性弱点的机制,在金融危机到来时尤其如此。只有对知识完全诚实,才可能在市场中生存、发展、壮大。

The market is a mechanism for discovering human weaknesses, especially when the financial crisis comes. Only by being completely honest with knowledge can we survive, develop and grow in the market.

Stock as a Piece of the Business

- Graham, Buffett, Munger, and Lu love the idea of being an owner of the businesses they invest in, as oppose to a trader (temporary holder). This ownership mentality is important for investors because it urges them to learn more about the business. Naseeb Talib talked about a similar concept in his book Skin in the Game. When an investor sees him/herself as an owner, the risk/reward ratio gets closer to 1 and becomes more balanced. This shift in mentality can also turn the investor into a helper of the business (time in addition to money) and a constructive critic when needed.

Margin of safety

- Margin of safety refers to the built-in cushion for downside risk in an investment. As we have established with the Mr. Market analogy above, the market is irrational and can stay irrational much longer than most think. Leaving a big gap between what you pay and what you believe to be the intrinsic value, is therefore recommended in order to stay solvent during the treacherous waves of the market.

Circle of Competence

-

Circle of competence literally means finding the limit to one’s knowledge and ability. Value investors tend to believe that the act of investing should be a reflection of one’s knowledge/wisdom. Hence, the most difficult thing for value investors is to figure out their own limitations and set up boundaries. These boundaries are meant to discipline themselves, so they do not get distracted by the “greener pastures” outside of their circle of competence. The two main questions we should always ask ourselves are:

- Where’s my knowledge border? What area/field of study/industry in which I am truly an expert?

- How do I know that I’m actually competent in this area? How do I know if/when I have achieved true mastery?

-

These are very tough questions to answer. When the market moves against you and everyone else is making money while you feel like the only loser in town, how do you maintain your conviction and know that you made the correct bet?

-

Lu thinks that when searching for your circle of competence, you have to find the smartest person who has the opposing view and be your devil’s advocate. If you are able to convince the other person, then you are closer to the truth and competency. You have to welcome criticism, build a team of people who have opposing views, who can challenge you on your ideas. After all these efforts, when you’ve convinced all the smart people you can find that your idea is superior, it’s still possible that there are blindspots. You will have to spend a lot of time to perfect your logic and knowledge, to be able to better understand the world and predict. Lu encourages investors to think like an economist, a sociologist, and a psychologist — in other words, think broadly and deeply.

is index investment advisable

-

from the us index market data (1802-1870 -> 6.7%, 1871 - 1925 -> 6.6%, 2000-2012, -0.1%), even in a prosperous market such as the United States for a long time, the index has performed very poorly in two time periods, and both lasted for more than 10 years, namely 1966-1981 and 2000-2012. Time period, no profit. If someone is unfortunate enough to just put their money in index investing during these two time periods, that’s pretty bad. 10 years is not a short time for a person’s life. If we have not made any profit in the stock market for such a long period of time, our belief basically does not exist.

-

So, the answer to this question varies from person to person, and if you’re comfortable with the status quo, or self-aware, it’s not bad to accept the returns of the index. But if you want to take it to the next level, learn how to pick stocks and make trading decisions.

A Few Additional Gems from the Book

Lu: Temperament

-

Value investors are loners who stick to independent thoughts and opinions. People who pay less attention to popular trends and opinions are usually better value investors. Lu believes that investors’ circle of competence rarely overlap, so it’s unnecessary to over-communicate. Since value investors aren’t believers in diversification, they would not need to invest in too many ventures. Also, the less time we spend talking with others about the new hot thing, the more time we have to figure out the couple of companies we are researching.

-

Value investors are rational and objective. People who are less affected by emotions are usually better value investors. There are countless books and articles warning beginner investors about their emotions, leading them to buy and sell at the exact wrong time.

-

Value investors are patient. Extremely patient. Berkshire is the perfect example of this, where they are willing to sit on a pile of cash for years or decades when they believe that there’s no attractive deals on the market within their circle of competence.

-

Value investors are also decisive. Decisiveness (quickness in action) is often seen as a characteristic that contradicts patience (slowness in action). However, a good value investor must possess both qualities. He or she must be willing to wait for as long as necessary (years) without making a move, but pounce on an opportunity boldly with big wagers when it presents itself (usually during bear market).

-

Value investors are passionate. Passion for learning is arguably the most important thing to a fulfilled life. As an investor, having passion for all aspects of business is certainly important as well. Charlie Munger often credits his success and longevity to his interest in money sense — his passion for business in general. He often says that a good investor must also be a good businessman. He or she needs to have a grasp on and curiosity in a business’ operations. This interest will largely guide research in questions like:

- What makes a company successful? Why does it make money?

- What would the future look like for an industry? What’s its competitive landscape?

Lu: Intellectual honesty

- Research questions usually yield no quick answers. Investment can be seen as a prediction of the future, and the future cannot be predicted most of the time. Therefore, researching for a future prediction is an activity with such low probability of success that one must be content with not finding any answers. Having low expectations, having a scientist’s mindset, and having a healthy relationship with failure and uncertainty are crucial for value investors.

Lu: Reading

- A large part of a value investors’ time should be spent reading. Readings should consist of everything and anything, but especially history, business history, and a lot of a company’s annual reports over the years. Munger is famous for being a biography nut. Buffett is known for spending 80% of his waking hours reading. By doing vast amount of reading, research, and analysis, one will have many past predictions formulate in their brain. This type of practice creates a particular smell for good investment that will become second nature for good value investors, helping them make more educated predictions in the future.

Lu: When to sell

-

- When you realize that you’ve made a mistake with your evaluation of the company through your research, sell immediately

-

- When you see a better opportunity with better bang for a buck, aka when the opportunity cost is becoming too high

-

- Valuation becomes too drastic, significantly derailing from the intrinsic value

-

Value should not be a number, but a range.

Lu: Avoid short selling

- Three characteristics of short selling that people may overlook:

- Theoretically, a stock can lose 100% of its value, yet the percentage of increase can be infinite. If you short a stock, you have to understand the asymmetric risk you are taking on.

- The best time to short a stock is usually when a company experiences some type of crisis. It can come in the form of a discovery of accounting fraud, insolvency, or otherwise. Oftentimes, fraud can exist for a long time for a company while the market continues to carry the stock forward, and since one must pay interest to short sell, the pressure of short squeeze may bankrupt an investment before the company goes under.

- Short selling exerts exuberant amount of pressure and occupies all mental capacity of an investor. Lu believes that the confusion and lack of mental clarity short selling creates is actually its deadliest sin. An investor often discount the opportunity cost of the disruption of concentration and sharpness that he/she should always possess. Lu believes that he lost many great investment opportunities during his time of being a short seller because of it.

- 真知灼见和频繁交易是互不相容的。这是我最大的错误

- Insight and frequent transactions are incompatible with each other. This is my biggest mistake

Lu: Interest rate today & margin of safety

- Low interest rate environments are historically rare. However, it is even rarer when all major countries around the world are doing the same QE / low interest rate / central bank interference. If one sees low interest rate as some sort of “discount rate”, then one may be wrong about his/her assessment of their “margin of safety”. The low interest rate environment 1) is usually temporary 2) should be seen as a warning sign, as it does not prevent the economy going further south. In this environment, one should set their margin of safety requirement to be a lot higher, not lower.

Lu: Management

- During a company’s infancy, or during a phase of transition, management is key when it comes to evaluating a company. During a time of normalcy, management hold relatively less importance in the value of a mature company. In china, most companies are still in its infancy, thus it’s more important to consider management as a part of the process of valuation.

Lu: Cycles

- When people start to talk about cycles, they stop being value investors. Nobody who is intellectually honest can predict cycles. When you get into the business of predicting cycles, you will find that besides longer cycles of bubbles, there are infinitely smaller cycles, down to weeks, and days. People fall into the trap of wasting more time chasing cycles than doing actual homework.

Quotes

Between the government and citizens (“ruler and subjects”): the government must effectively and intelligently protect the safety of the people and their property, this being the equivalent of the obligation in the olden days of rulers to be “competent rulers”, while the citizens must pay taxes to the government, obey the government’s laws, serve with loyalty and the utmost diligence when recruited or conscripted by by the government, and when appropriate give opinions to the government or try to dissuade the government, these being the equivalent of the obligation in the olden days of subjects to be loyal;

Between parents and offspring: parents must raise and educate the offspring, while the offspring must carry out xiao (“be good to parents”) and support and care for aged, weak parents;

Between husband and wife: both must be of one heart and mind, and help each other to together build a family life where both the next generation is raised and the previous generation is cared for;

Among siblings: older siblings must be kind and helpful to the younger ones, the younger siblings must be respectful to the older ones, and all siblings must help each other;

Among friends: friends must help each other, especially with mutual encouragement, mutual advice, and dissuasion from what is wrong.

More seriously, the lack of ethical standards among strangers is one of the important reasons for the lack of business integrity, and integrity is the lubricant of a free market economy.

References

- https://medium.com/@jyz/on-civilization-and-china-in-li-lus-new-book-%E6%96%87%E6%98%8E-%E7%8E%B0%E4%BB%A3%E5%8C%96-%E4%BB%B7%E5%80%BC%E6%8A%95%E8%B5%84%E4%B8%8E%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD-88ee31ab6431

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/value-investing-li-lus-new-book-%E6%96%87%E6%98%8E%E7%8E%B0%E4%BB%A3%E5%8C%96%E4%BB%B7%E5%80%BC%E6%8A%95%E8%B5%84%E4%B8%8E%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD-joey-zhou/

- https://monkeyenroute.medium.com/book-review-civilization-modernization-value-investing-china-by-li-lu-22398102583c

- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLaI5haAUho4P2KFKH-XXAAfKbXm0w_NmH