-

Howard Marks explains the pattern of cycles found in markets, the economy, and business. An investor who understands the different cycles — the history, the driving factors, their interconnectedness, and the role of psychology — can avoid common errors and best position their portfolio for success

-

We notice and remember patterns in order to make decisions easier, less painful, and more beneficial, so we don’t think through every decision from scratch.

-

Economies, businesses, and markets follow a pattern of cycles. These cycles are irregular because of the swings in humans psychology and behavior.

-

Elements of a Winning Investment Philosophy:

- Accounting, finance, and economics education

- An understanding of how markets work

- Reading (broadly) is essential to learning and questioning what you’ve previously learned

- Exchanging ideas with other investors

- Experience

-

If we all have the same information, come to the same conclusions, act on it in the same way, then outperformance is unlikely.

-

Buffett’s criteria for desirable information: 1) has to be important, and 2) has to be knowable. Macroeconomic info (forecasting) fails one of those two, usually the latter because it’s not knowable, or not knowable consistently enough to produce long-term outperformance.

-

Time is best spent on:

- Knowing the knowable: the fundamentals of business, sectors, industries.

- Better behavior: more discipline around price relative to fundamentals.

- Understanding cycles: know where we are in the cycle and how to position a portfolio for it.

-

Portfolio risk management is a balancing act between aggressive and defensive, adjusted over time.

-

In investing, the future is a range of possibilities — some known, some unknown — making risk and uncertainty unavoidable. The range of possibilities is best viewed as a probability distribution. That leads to knowing the most likely outcome, on average, in the long run. “Most likely” is not guaranteed across any single event (think coin tosses). Randomness in any one event can lead to a unlikely outcome.

-

Any opinion on the future should be based on: 1) what’s going to happen, and 2) the likelihood of being correct.

-

Questions to ask about the current cycle for those who study past cycles:

- Is it closer to the beginning upswing or the peak leading to a downswing?

- Has it been rising for a while? To the point of being dangerous?

- Does investor behavior suggest greed or fear?

- Are investors appropriately risk-averse or excessively risk-tolerant?

- Is the market overpriced or cheap due to the cycle?

- Does the current point in the cycle emphasize an aggressive or defensive portfolio stance?

- These questions should help determine the tilt of a portfolio: more aggressive when the odds are in our favor and more defensive when the odds are against us.

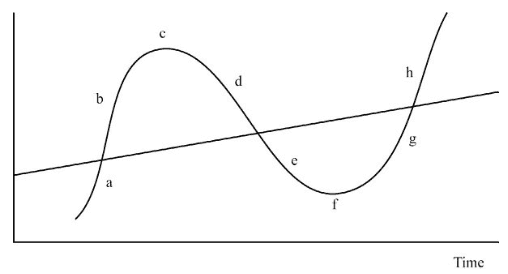

Nature of Cycles: Swings of Cycles

-

Cycles are a continuous swing around a midpoint, which is often a longer-term trend.

-

The swings follow a generic pattern of: a) recovery from the lows, b) rise past the midpoint to (extreme) highs, c) the new high, d) downward correction, e) fall past the midpoint to the low, f) the new low, g) recovery from the low, and h) back past the midpoint to another high.

-

Because cycles are influenced in the short term by people and other variables, it has no constant rate. The duration and speed of each section varies and inevitably causes the next.

-

Regression to the mean is the move back to the midpoint from the high and low. It’s the powerful self-correcting mechanism in all cycles.

-

But the force behind regression continues to exert itself, the momentum pushes the cycle past the midpoint to the next high or low.

-

Those who don’t understand cycles will be surprised by, and often contribute to, it. Those who do understand will find opportunities in it.

-

Extremes are not guaranteed for every swing, but cycles that reach extremes in one direction are often followed by an opposite extreme in the other direction.

-

The general pattern of a cycle matters, because the specific details at any point in a cycle will look different from similar points in the past.

-

Randomness makes recognizing the pattern in cycles more complicated and less predictable and dependable. The influence of people, their inconsistent behavior, emotions, and actions add to the randomness.

-

The Economic Cycle:

- The long term economic cycle follows fundamental factors that produce a steady average growth rate over a longer secular trend.

- Factors include: population growth which impacts hours worked and GDP growth which is affected by demographic shifts, education, technology/innovation, automation, and globalization.

- Within the longer secular trend, are short term cycles too.

- The short term economic cycle is driven by changing variables within a population — the people. For instance, spending fluctuates based on the fear of unemployment. The lack of fear or the “wealth effect” can spur spending. It can create a self-fulfilling prophecy. If people (or companies) believe there’s a recession on the horizon, they spend less (companies hold off on new projects), and the economy inevitably slides into a recession.

- Most economic forecasts extrapolate the current trend because it’s safe (career risk) and sticks to the status quo. Those forecasts are likely already priced into the market and offer no performance benefit.

- Valuable forecasts are outliers that result in surprises that deviate from the trend dramatically. The downside is outliers rarely occur, are hard to predict, and usually wrong — thus can be costly.

- Inflation is a result of increasing demand for goods relative to supply, an increase in raw materials and labor costs, and/or when a currency tied to imports declines relative to a currency tied to exports.

- Central Banks have a mandate to control inflation and stimulate employment. The two often work in opposition – steps to stimulate one, contract the other.

- Keynesian economics: Keynes believed the government should step in to prop up a weak economy through spending/running a deficit but reduce spending/running a surplus in a strong economy.

-

The Profit Cycle:

- Generally, the swings in the economy influence the rise and fall of corporate sales, which impacts profits.

- Commodity, raw material, and basic components see demand rise and fall with the economic cycle. Luxury goods, travel, cars (consumer discretionary), and homes do too.

- Basic necessities (consumer staples) like food and medicine are less responsive to the economic cycle. Consumers may trade down — buy cheaper, lower-cost brands in a recession versus expansion.

- Company profits follow a cycle similar to the economy but not all companies follow the same pattern.

- Higher sales do not guarantee higher profits.

- Two Types of Leverage:

- Operating Leverage: Most businesses have a combination of fixed and variable costs, meaning costs will fluctuate. So profits depend on the variability of revenues and costs (Profits = Revenues – Costs). Management has some control over profits by managing the variable costs (layoffs, store/factory closures) but it usually takes time and may increases costs in the short-run.

- Financial Leverage: Debt – cost is tied to interest payments, which rises and falls based on the amount of debt and/or interest rate being charged.

- A host of independent developments — management decisions, technology changes, regulations, taxation, geopolitical events, natural disasters, etc. — impact profits too, making it hard to predict.

-

Investor Psychology (Human Nature Cycle):

- Changes in psychology affect the economic, profit, and market cycle.

- The market pendulum swings from greed to fear, optimism to pessimism, risk-tolerant to risk-averse, overpriced to underpriced, and focused on the infinite future to the immediate present. An excess in one direction sets the stage for the swing back.

- In addition, yearly market returns fluctuate across a wide range. In other words, earning the average market return in any year is rare. From 1970 to 2016, the return on the S&P 500 fell within 2% of its average only 3 times! In fact, investors are more likely to experience an extreme return than the average. The wide range of returns in any given year is a good example of investor psychology at work (business fundamentals don’t change that drastically from year to year).

- “This cycle in investors’ willingness to value the future is one of the most powerful cycles that exist. A simple metaphor relating to real estate helped me to understand this phenomenon: What’s an empty building worth? An empty building (a) has a replacement value, of course, but it (b) throws off no revenues and (c) costs money to own, in the form of taxes, insurance, minimum maintenance, interest payments and opportunity costs. In other words, it’s a cash drain. When investors are in a pessimistic mood and can’t see more than a few years out, they can only think about the negative cash flows and are unable to imagine a time when the building will be rented and profitable. But when the mood turns upward and interest in future potential runs high, investors envision it full of tenants, throwing off vast amounts of cash, and thus salable at a fancy price. Fluctuation in investors’ willingness to ascribe value to possible future developments represents a variation on the full-or-empty cycle. Its swings are enormously powerful and mustn’t be underestimated.”

- All investors deal with emotion. The superior investor keeps their emotions in balance and takes an objective approach to investing.

- Two failings of an emotional investor: biased perception and interpretation. Investors rarely take a balanced approach to good and bad news. They focus on one-side, leading to a biased view of events. For instance, economic data is twisted in a positive or negative light depending on the prevailing emotion.

-

The Risk Cycle:

- Investing is “bearing risk in pursuit of profit. Investors try to position portfolios so as to profit from future developments rather than be penalized by them.”

- The risk lies in the future not being perfectly knowable. Uncertainty exists.

- How investors behave toward risks influences the market.

- Risk Aversion: the preference for safety over risk (loss). Most investors are risk-averse. They prefer a certain 7% return over a possible 7% return. An incrementally higher return is required for risk-averse investors to take on risk.

- In theory, risk-averse investors police the market. They’re cautious, analyze investments objectively, use conservative assumptions, require a margin of safety, insist on a requisite return for the risk taken, and avoid investments without it. But that’s not what happens.

- Changing attitudes towards risk leads investors to be too risk-averse or too risk-tolerant at times. Periods dominated by good news, optimism, greed, and euphoria push investors to be more risk-tolerant than normal. Periods dominated by bad news, pessimism, and fear lead investors to be more risk-averse than normal.

- In other words, risk is highest when investors perceive risk to be lowest. When the collective investor is most risk-averse they should be most risk-tolerant and vice versa. The reward for taking risk is greatest when investors are most risk-averse and vice versa. Opportunity seeking should be highest at peak risk-aversion.

- Corporate management is not immune to the swings from risk-averse to risk-tolerant either (see the financial crisis).

-

The Credit Cycle:

- Marks believes the credit cycle is the most volatile cycle and has the greatest impact on asset prices.

- The credit cycle — the ability for businesses to borrow quickly and easily — swings from wide open to closed.

- Companies turn to credit markets to finance growth and refinance maturing debt. Financial companies depend on credit markets to operate their business smoothly. When the credit window is closed, credit is difficult/impossible to get, and it negatively impacts asset prices. A closed credit market can lead to widespread panic and fear.

- The credit cycle is an example of lenders, borrowers, and investors swinging between risk-averse and risk-tolerant.

- Lenders move from a cautious, risk-averse position unwilling to lend without higher rates and protection from losses to a risk-tolerant, willingness to lend at lower rates and no protection in place out of fear of missing out.

- Excessive lending often inflates a bubble and creates a crisis.

- Most raging bull markets are abetted by an upsurge in the willingness to provide capital, usually imprudently. Likewise, most collapses are preceded by a wholesale refusal to finance certain companies, industries, or the entire gamut of would-be borrowers.

-

The Distressed Debt Cycle:

- Bonds and other debt securities are typically bought for the yield and the return of principal at maturity.

- Distressed debt is bought on the basis that the company can no longer pay the interest and principal. When a company files for bankruptcy the equity shareholders are wiped out and debt holders become the new owners of the company. Distressed debt is bought on the anticipation that the new ownership interest in the company (after it emerges from bankruptcy) is worth significantly more than the value of the distressed debt.

- Distressed debt investing is cyclical and dependant on other cycles.

- It requires two ingredients: “unwise extension of credit” and “an igniter.” The igniter is usually a recession or credit crunch making it difficult for companies to service their bonds and/or refinance. Those bonds begin to fall in price, selling capitulates until failure is priced in.

-

The Real Estate Cycle:

- The real estate cycle has similar ingredients as other cycles — rising optimism, increased activity, higher prices, until it goes too far — but also includes the added time needed for development, involves higher leverage, and adjusting to supply/demand changes is more difficult/less flexible than other industries.

- Real estate development deals with delays, regulations, zoning issues, local approval, financial approval, and construction. It takes months to years to over a decade to complete a project. A lot can happen in the real estate market in the time span.

- The risk is completing a project while the economy is headed for recession with a rising supply/shrinking demand in the market. It’s also an opportunity for would-be buyers.

- The other risk is not knowing what other developers are doing/thinking. If every developer sees home prices rising and wants to start a project, that ends around the same time, it could lead to excessive supply, lower prices, and lower profits.

-

Asset prices are driven mostly by fundamentals and psychology, often more so by the psychological response to changing fundamentals.

-

The combination of the two — fundamentals and psychology — is what makes investing imprecise.

-

Investor psychology affects and magnifies cycles. It’s also the driven force behind mistakes and losses.

-

3 Stages of a Bull Market: 1) when few people believe things will get better, 2) when most people see things improving, 3) when everyone believes things will stay better forever.

-

3 Stages of a Bear Market: 1) when a few people believe things won’t stay better forever, 2) when most people see things are getting worse, 3) when everyone believes things can only get worse.

-

Bubbles are blown by investor psychology and the suspension of fundamental analysis.

-

The key is recognizing where investor psychology and market valuation sits in the cycle.

-

Where the market stands in the cycle dictates the future probabilities on returns. A market near the bottom of its cycle has a higher probability of higher returns than one closer to the top. Where the market stands in the cycle dictates the likeliness of future outcomes.

-

When to buy? You won’t know when the market bottoms. The risk of waiting “for the bottom” is in missing it and the rally that follows. Better to buy when the price is below value because you can always buy more if the price continues to fall.

-

The risk is learning the wrong lessons from past cycles. — Marks references the 2008 crisis and investors’ “learning” that the market always quickly recovers because that was the outcome following the crisis. It fails to consider the alternative outcomes at the depths of the crisis. It could lead to investor behavior that amplifies future cycles because they learned the wrong lesson.

-

Investors deal with two sources of error: the risk of losing money and the risk of missing opportunities. Removing one risks exposure to the other. Investing is about balancing the two — between aggressive and defensive. It should be adjusted as you move through a market cycle, assuming you can handle being wrong at times.

-

Investment success is ultimately determined by positioning, asset selection, aggressiveness/defensiveness, skill, and luck.

-

Positioning: deciding the appropriate portfolio risk level — more/less risk-averse or risk-tolerant — based on the location in the cycles. Positioning increases or decreases the odds of outperformance.

-

Asset Selection: identify asset classes/securities that will be better or worse and weighting — over and under — them based on the required risk level of the portfolio.

-

Skill and luck determine the outcome of decisions. Luck plays a larger role in the short term than most will admit.

-

Not knowing the future means being prepared for things that may not go as planned from a portfolio perspective.

-

Exploiting market extremes offer the highest odds of success. Between the extremes, the odds become less certain because prices lie closer to value.

-

Investing requires humility and confidence. Confidence to stick with a strategy when it fails to produce the results you expect but enough humility to know your own limitations. Yet, success often undermines both, leaving investors less humble and overconfident.

-

Future cycles will continue to be driven by the collective emotions and decisions of people.

Quotes

“The plain truth is, there’s little of value to be learned from success. People who are successful run the risk of overlooking the fact that they were lucky, or that they had help from others. In investing, success teaches people that making money is easy, and that they don’t have to worry about risk—two particularly dangerous lessons.”

“We can’t create great opportunities to time the market through our understanding of cycles. Rather, the market will decide when we’ll have them. Remember, when there’s nothing clever to do, the mistake lies in trying to be clever.”

“After 28 years at this post, and 22 years before this in money management, I can sum up whatever wisdom I have accumulated this way: The trick is not to be the hottest stock-picker, the winningest forecaster, or the developer of the neatest model; such victories are transient. The trick is to survive! Performing that trick requires a strong stomach for being wrong because we are all going to be wrong more often then we expect. The future is not ours to know. But it helps to know that being wrong is inevitable and normal, not some terrible tragedy, not some awful failing in reasoning, not even bad luck in most instances. Being wrong comes with the franchise of an activity whose outcome depends on an unknown future…” — Peter Bernstein

“As any system grows toward its maximum or peak efficiency, it will develop the very internal contradictions and weaknesses that bring about its eventual decay and demise.” — Peter Kaufman

“The study of cycles is really about how to position your portfolio for the possible outcomes that lie ahead.”

“There are two kinds of people who lose a lot of money: those who know nothing and those who know everything.” — Henry Kaufman, Salomon Brothers chief economist

“Short-term investment performance is largely a popularity contest, and most bargains exist for the simple reason that they haven’t yet been taken up by the herd and become popular. On the contrary, assets that have performed well are usually the ones that have gained in popularity because of their obvious merit and thus have become high-priced.”

“In investing, everything that’s important is counter-intuitive, and everything that’s obvious to everyone is wrong.”

“The tendency of people to go to excess will never end. And thus, since those excesses eventually have to correct, neither will the occurrence of cycles. Economies and markets have never moved in a straight line in the past, and neither will they do so in the future. And that means investors with the ability to understand cycles will find opportunities for profit.”

“There are three ingredients for success—aggressiveness, timing and skill—and if you have enough aggressiveness at the right time, you don’t need that much skill.”

“It’s important to note that exiting the market after a decline—and thus failing to participate in a cyclical rebound—is truly the cardinal sin in investing. Experiencing a mark-to-market loss in the downward phase of a cycle isn’t fatal in and of itself, as long as you hold through the beneficial upward part as well. It’s converting that downward fluctuation into a permanent loss by selling out at the bottom that’s really terrible.”

“Falling for the sure thing—the asset that will provide return without risk, or what I call the “silver bullet”—is one of investors’ greatest recurring failings.”

“There is no such thing as a market that is separate from—and unaffected by—the people who make it up. The behavior of the people in the market changes the market. When their attitudes and behavior change, the market will change.”

“The key questions can be boiled down to two: how are things priced, and how are investors around us behaving?”

“No asset or company is so good that it can’t become overpriced.”

“There’s only one form of intelligent investing, and that’s figuring out what something’s worth and buying it for that price or less. You can’t have intelligent investing in the absence of quantification of value and insistence on an attractive purchase price. Any investment movement that’s built around a concept other than the relationship between price and value is irrational.”

“There is nothing as disturbing to one’s well-being and judgment as to see a friend get rich.” — Charles Kindleberger, Manias, Panics, and Crashes

“Few things are as costly as paying for potential that turns out to have been overrated.”

“Our job as investors is simple: to deal with the prices of assets, assessing where they stand today and making judgments regarding how they will change in the future.”

“Conscientious belief in the inevitability of cycles like I’m urging means that a number of words and phrases must be excluded from the intelligent investor’s vocabulary. These include “never,” “always,” “forever,” “can’t,” “won’t,” “will” and “has to.""

“It’s not for nothing that they often say cynically—in tougher times, when optimistic generalizations can no longer be summoned forth—that “only the third owner makes money.” Not the developer who conceived and initiated the project. And not the banker who loaned the money for its construction and then repossessed the project from the developer in the down-cycle. But rather the investor who bought the property from the bank amid distress and then rode the up-cycle.”

“In making investments, it has become my habit to worry less about the economic future—which I’m sure I can’t know much about—than I do about the supply/demand picture relating to capital. Being positioned to make investments in an uncrowded arena conveys vast advantages. Participating in a field that everyone’s throwing money at is a formula for disaster.”

“When risk tolerance takes over and lenders compete avidly for opportunities, the bidding is likely to become overheated. The resulting opportunity to lend is likely to be at too high a price: a yield that’s too low and/or risk that’s excessive. Thus an overheated auction in the credit market—as elsewhere—is likely to produce a “winner” who’s really a loser. This is the process I call the race to the bottom.”

“Prosperity brings expanded lending, which leads to unwise lending, which produces large losses, which makes lenders stop lending, which ends prosperity, and on and on.”

“Superior investing doesn’t come from buying high-quality assets, but from buying when the deal is good, the price is low, the potential return is substantial, and the risk is limited… The slammed-shut phase of the credit cycle probably does more to make bargains available than any other single factor.”

“In investing, there is nothing that always works, since the environment is always changing, and investors’ efforts to respond to the environment cause it to change further.”

“In my view, risk is primarily the likelihood of permanent capital loss. But there’s also such a thing as opportunity risk: the likelihood of missing out on potential gains. Put the two together and we see that risk is the possibility of things not going the way we want.”

“Essentially risk says we don’t know what’s going to happen… We walk every moment into the unknown. There’s a range of outcomes, and we don’t know where [the actual outcome is] going to fall within the range. Often we don’t know what the range is.” — Peter Bernstein

“Risk means more things can happen than will happen.” — Elroy Dimson

“The events in the life of a cycle shouldn’t be viewed merely as each being followed by the next, but — much more importantly — as each causing the next.”

“Most people understand that busts follow booms. Somewhat fewer grasp the fact that the busts are caused by the booms.”

“The greatest lessons regarding cycles are learned through experience…as in the adage ‘experience is what you got when you didn’t get what you wanted.‘”

“Societies rise and fall, and they speed up and slow down in terms of economic growth relative to each other. This underlying trend in growth clearly follows a long-term cycle, although the short-run ups and downs around it are more discernible and thus more readily discussed.”

“All these people see the same data, read the same material, and spend their time trying to guess what each other is going to say. [Their forecasts] will always be moderately right—and almost never of much use.” — Milton Friedman

“We have two classes of forecasters: those who don’t know — and those who don’t know they don’t know.” — John Kenneth Galbraith

“The mood swings of the securities markets resemble the movement of a pendulum. Although the midpoint of its arc best describes the location of the pendulum “on average,” it actually spends very little of its time there. Instead, it is almost always swinging toward or away from the extremes of its arc. But whenever the pendulum is near either extreme, it is inevitable that it will move back toward the midpoint sooner or later. In fact, it is the movement toward an extreme itself that supplies the energy for the swing back.”

“The vast majority of the highly superior investors I know are unemotional by nature. In fact, I believe their unemotional nature is one of the great contributors to their success.”

“In the real world, things generally fluctuate between “pretty good” and “not so hot.” But in the world of investing, perception often swings from “flawless” to “hopeless.” The pendulum careens from one extreme to the other, spending almost no time at “the happy medium” and rather little in the range of reasonableness. First there’s denial, and then there’s capitulation.”

“Since risk (that is, uncertainty with regard to future developments, and the possibility of bad outcomes) is the primary source of the challenge in investing, the ability to understand, assess and deal with risk is the mark of the superior investor and an essential—I’m tempted to say the essential—requirement for investment success.”

“Good times cause people to become more optimistic, jettison their caution, and settle for skimpy risk premiums on risky investments. Further, since they are less pessimistic and less alarmed, they tend to lose interest in the safer end of the risk/return continuum. This combination of elements makes the prices of risky assets rise relative to safer assets. Thus it shouldn’t come as a surprise that more unwise investments are made in good times than in bad.”

“For me, the bottom line of all of this is that the greatest source of investment risk is the belief that there is no risk. Widespread risk tolerance—or a high degree of investor comfort with risk—is the greatest harbinger of subsequent market declines.”

“What’s the greatest source of investment risk? … It comes when asset prices attain excessively high levels as a result of some new, intoxicating investment rationale that can’t be justified on the basis of fundamentals, and that causes unreasonably high valuations to be assigned. And when are these prices reached? When risk aversion and caution evaporate and risk tolerance and optimism take over. This condition is the investor’s greatest enemy.”

“When total fear replaces a high degree of confidence, excessive risk aversion takes the place of unrealistic risk tolerance.”

“If I could ask only one question regarding each investment I had under consideration, it would be simple: How much optimism is factored into the price?”

“There can be few fields of human endeavor in which history counts for so little as in the world of finance. Past experience, to the extent that it is part of memory at all, is dismissed as the primitive refuge of those who do not have the insight to appreciate the incredible wonders of the present.” — John Kenneth Galbraith, A Short History of Financial Euphoria

“The less prudence with which others conduct their affairs, the greater the prudence with which we should conduct our own affairs.” — Warren Buffett

“It’s hard to fully understand most phenomena in the investment world unless you’ve lived through them.”