Luhmann’s slip-box

-

Ahrens’ approach to note-taking was inspired by the 20th-century German sociologist Niklas Luhmann (1927-1998). Luhmann was a prolific note-taker, writer, and academic. Early in his academic career, Luhmann realized that a note was only as valuable as its context – its network of associations, relationships, and connections to other information.

-

He developed a simple system based on paper index cards, which he called his “slip-box” (or zettelkasten in German). It was designed to connect any given note to as many different potentially relevant contexts as possible.

-

Luhmann rejected alphabetical categorization of his notes, along with fixed categories like the Dewey Decimal System. He intended his notes not just for a single project or book but for a lifetime of reading and researching. He designed his slip-box as a research database made up of index cards (zettel) that were “thematically unlimited” and could be infinitely extended in any direction.

-

Although it appeared to be just a simple filing system made up of index cards, Luhmann’s slip-box grew to become an equal thinking partner in his work. He described his system as his secondary memory (zweitgedächtnis), alter ego, or reading memory (lesegedächtnis). He reported that it continuously surprised him with ideas he’d forgotten he had. Because of this, he claimed that there was actual communication going on between himself and his zettelkasten. As he built up his collection of notes, he embarked on a series of achievements that would eventually make him one of the most influential sociologists and scientists of the 20th century.

-

Here’s how it worked:

-

Luhmann wrote down interesting or potentially useful ideas he encountered in his reading on uniformly sized index cards

-

He wrote only on one side of each card to eliminate the need to flip them over, and he limited himself to one idea per card so they could be referenced individually

-

Each new index card received a sequential number, starting at 1. When a new source was added to that topic, or he found something to supplement it, he would add new index cards with letters as suffixes (1a, 1b, 1c, etc.)

-

These branching connections were marked in red as close as possible to the point where the branch began

-

Any of these branches could also have their own branches. The card for fellow German sociologist Jürgen Habermas, for example, was labeled 21/3d26g53

-

As he read, he would create new cards, update or add comments to existing ones, create new branches from existing cards, and create new links between cards on different “strands”

-

This diagram shows how subtopics branched off from main topics:

-

-

Not only did this create a system that could extend infinitely in any direction, but it also gave each index card a permanent ID number. This number could be referenced from any other card, because it would never change. The branches created “strands” of thought that one could enter at any point, following it downstream to be elaborated upon or upstream to its source.

It also led to a meaningful topography within the system: Topics that had been extensively explored had long reference numbers, making their length informative on its own. There is no hierarchy in the zettelkasten, which means it can grow internally without any preconceived scheme. By creating notes as a decentralized network instead of a hierarchical tree, Luhmann anticipated hypertext and URLs.

Principle #1: Writing is not the outcome of thinking; it is the medium in which thinking takes place

Writing doesn’t begin when we sit down to put one paragraph after another on the screen or page. It begins much, much earlier, as we take notes on the articles or books we read, the podcasts or audiobooks we listen to, and the interesting conversations and life experiences we have.

These notes build up as a byproduct of the reading we’re already doing anyway. Even if you don’t aim to develop a grand theory, you need a way to organize your thoughts and keep track of the information you consume.

If you want to learn and remember something long-term, you have to write it down. If you want to understand an idea, you have to translate it into your own words. If we have to do this writing anyway, why not use it to build up resources for future publications?

Writing is not only for proclaiming fully formed opinions, but for developing opinions worth sharing in the first place.

Writing works well in improving one’s thinking because it forces you to engage with what you’re reading on a deeper level. Just because you read more doesn’t automatically mean you have more or better ideas. It’s Iike learning to swim – you have to learn by doing it, not by merely reading about it.

The challenge of writing as well as learning is therefore not so much to learn, but to understand, as you will already have learned what you understand. When you truly understand something, it is anchored to a latticework of related ideas and meanings, which makes it far easier to remember.

For example, you could memorize the fact that arteries are red and veins are blue. But it is only when you understand why – that arteries carry oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the rest of the body, while veins carry blood low in oxygen back to the heart – that that fact has any value. And once we make this meaningful connection between ideas, it’s hard not to remember it.

The problem is that the meaning of something is not always obvious. It requires elaboration – we need to copy, translate, re-write, compare, contrast, and describe a new idea in our own terms. We have to view the idea from multiple perspectives and answer questions such as “How does this fact fit with others I already know?” and “How can this phenomenon be explained by that theory?” or “How does this argument compare to that one?”

Completing these tasks is exceedingly difficult inside the confines of our heads. We need an external medium in which to perform this elaboration, and writing is the most effective and convenient one ever invented.

Principle #2: Do your work as if writing is the only thing that matters

In academia and science, virtually all research is aimed at eventual publication Ahrens notes that “there is no such thing as private knowledge in academia. An idea kept private is as good as one you never had.”

The purpose of research is to produce public knowledge that can be scrutinized and tested. For that to happen, it has to be written down. And once it is, what the author meant doesn’t matter – only the actual words written on the page matter.

This principle requires us to expand our definition of “publication” beyond the usual narrow sense. Few people will ever publish their work in an academic journal or even on a blog. But everything that we write down and share with someone else counts: notes we share with a friend, homework we submit to a professor, emails we write to our colleagues, and presentations we deliver to clients all count as knowledge made public.

This might still seem like a radical principle. Should we publicize even the ideas we’ve only just encountered, or opinions half-formed, or wild theories we can’t substantiate? Do we really need even more people broadcasting half-baked opinions and theories online?

But the important part is the principle: Work as if writing is the only thing that matters. Having a clear, tangible purpose when you consume information completely changes the way you engage with it. You’ll be more focused, more curious, more rigorous, and more demanding. You won’t waste time writing down every detail, trying to make a perfect record of everything that was said. Instead, you’ll try to learn the basics as efficiently as possible so you can get to the point where open questions arise, as these are the only questions worth writing about.

Almost every aspect of your life will change when you live as if you are working toward publication. You’ll read differently, becoming more focused on the parts most relevant to the argument you’re building. You’ll ask sharper questions, no longer satisfied with vague explanations or leaps in logic. You’ll naturally seek venues to present your work, since the feedback you receive will propel your thinking forward like nothing else. You’ll begin to act more deliberately, thinking several steps beyond what you’re reading to consider its implications and potential.

Deliberate practice is the best way to get better at anything, and in this case, you are deliberately practicing the most fundamental skill of all: thinking. Even if you never actually publish one line of writing, you will vastly improve every aspect of your thinking when you do everything as if nothing counts except writing.

Principle #3: Nobody ever starts from scratch

One of the most damaging myths about creativity is that it starts from nothing. The blank page, the white canvas, the empty dance floor: Our most romantic and universal artistic motifs seem to suggest that “starting from scratch” is the essence of creativity.

This belief is reinforced by how writing is typically taught: We are told to “pick a topic” as a necessary first step, then to conduct research, discuss and analyze it, and finally come to a conclusion.

But how can you decide on an interesting topic before you’ve read about it? You have to immerse yourself in research before you even know how to formulate a good question. And the decision to read about one subject versus another also doesn’t appear out of thin air. It usually comes from an existing interest or understanding. The truth is every intellectual endeavor starts with a preceding conception.

This is the tension at the heart of the creative process: You have to research before you pick what you will write about. Ideally, you should start researching long before, so you have weeks and months and even years of rich material to work with as soon as you decide on a topic. This is why an external system to record your research is so critical. It doesn’t just enhance your writing process; it makes it possible.

And all this pre-research also involves writing. We build up an ever-growing pool of externalized thoughts as we read. When the time comes to produce, we aren’t following a blindly invented plan plucked from our unreliable brains. We look in our notes and follow our interests, curiosity, and intuition, which are informed by the actual work of reading, thinking, discussing, and taking notes. We never again have to face that blank screen with the impossible demand of “thinking of something to write about.”

No one ever really starts from scratch. Anything they come up with has to come from prior experience, research, or other understanding. But because they haven’t acted on this fact, they can’t track ideas back to their origins. They have neither supporting material nor accurate sources. Since they haven’t been taking notes from the start, they either have to start with something completely new (which is risky) or retrace their steps (which is boring).

It’s no wonder that nearly every guide to writing begins with “brainstorming.” If you don’t have notes, you have no other option. But this is a bit like a financial advisor telling a 65-year-old to start saving for retirement – too little, too late.

Taking notes allows you to break free from the traditional, linear path of writing. It allows you to systematically extract information from linear sources, mix and shake them up together until new patterns emerge, and then turn them back into linear texts for others to consume.

You’ll know you’ve succeeded in making this shift when the problem of not having enough to write about is replaced by the problem of having far too much to write about. When you finally arrive at the decision of what to write about, you’ll already have made that decision again and again at every single step along the way.

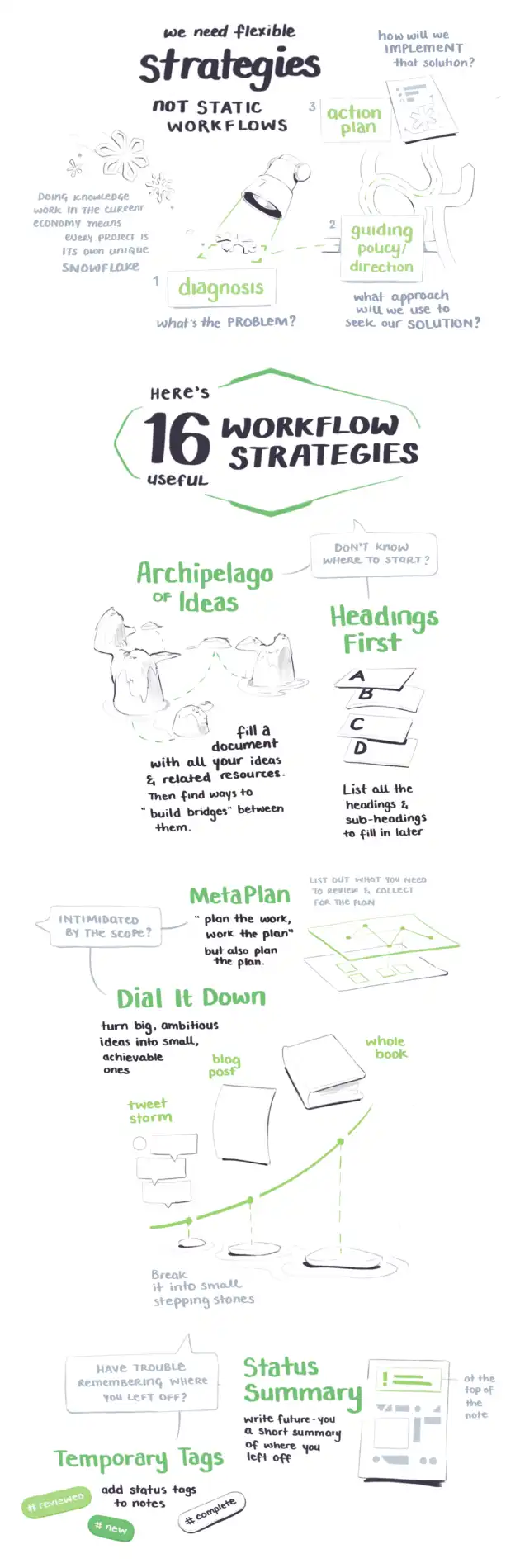

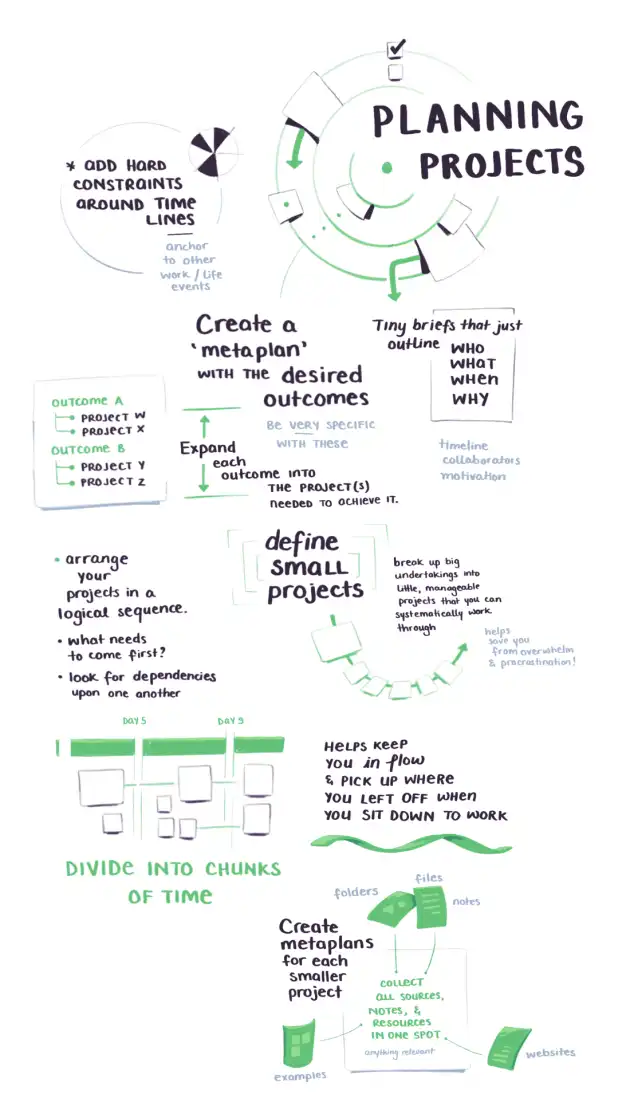

Principle #4: Our tools and techniques are only as valuable as the workflow

Just because writing is not a linear process doesn’t mean we should go about it haphazardly. We need a workflow – a repeatable process for collecting, organizing, and sharing ideas.

Writing is often taught as a collection of “tips and tricks” – brainstorm ideas, make an outline, use a three-paragraph structure, repeat the main points, use vivid examples, set a timer. Each one in isolation might make sense, but without the holistic perspective of how they fit together, they add more work than they save. Every additional technique becomes its own project without bringing the whole much further forward. Before long, the whole mess of techniques falls apart under its own weight.

It is only when all the work becomes part of an integrated process that it becomes more than the sum of its parts. Even the best techniques won’t make a difference if they are used in conflicting ways. This is why the slip-box isn’t yet another technique. It is the system in which all the techniques are linked together.

Good systems don’t add options and features; they strip away complexity and distractions from the main work, which is thinking. An undistracted brain and a reliable collection of notes is pretty much all we need. Everything else is just clutter.

Principle #5: Standardization enables creativity

Container shipping is a simple idea: ship products in standardized containers instead of loading them onto ships haphazardly as had always been done. But it took multiple failed attempts before it was successful, because it wasn’t actually about the container, which after all is just a box.

The potential of the shipping container was only unleashed when every other part of the shipping supply chain was changed to accommodate it. From manufacturing to packaging to final delivery, the design of ships, cranes, trucks, and harbors all had to align around moving containers as quickly and efficiently as possible. Once they did, international shipping exploded, setting the stage for Asia to become an economic power among many other historic changes.

Many people still take notes, if at all, in an ad-hoc, random way. If they see a nice sentence, they underline it. If they want to make a comment, they write it in the margins. If they have a good idea, they write it in whichever notebook is close at hand. And if an article seems important enough, they might make the effort to save an excerpt. This leaves them with many different kinds of notes in many different places and formats. This means when it comes time to write, they first have to undertake a massive project to collect and organize all these scattered notes.

Notes are like shipping containers for ideas. Instead of inventing a new way to take notes for every source you read, use a completely standardized and predictable format every time. It doesn’t matter what the notes contain, which topic they relate to, or what medium they arrived through – you treat each and every note exactly the same way.

It is this standardization of notes that enables a critical mass to build up in one place. Without a standard format, the larger the collection grows, the more time and energy have to be spent navigating the ever-growing inconsistencies between them. A common format removes unnecessary complexity and takes the second-guessing out of the process. Like LEGOs, standardized notes can easily be shuffled around and assembled into endless configurations without losing sight of what they contain.

The same principle applies to the steps of processing our notes. Consider that no single step in the process of turning raw ideas into finished pieces of writing is particularly difficult. It isn’t very hard to write down notes in the first place. Nor is turning a group of notes into an outline very demanding. It also isn’t much of a challenge to turn a working outline full of relevant arguments into a rough draft. And polishing a well-conceived rough draft into a final draft is trivial.

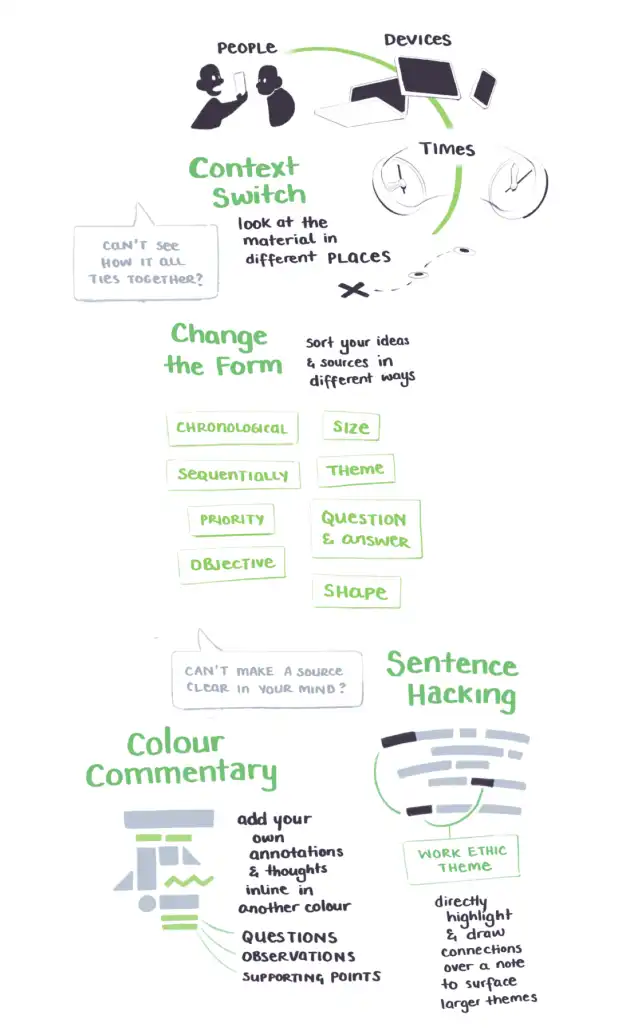

So if each individual step is so easy, why do we find the overall experience of writing so grueling? Because we try to do all the steps at once. Each of the activities that make up “writing” – reading, reflecting, having ideas, making connections, distinguishing terms, finding the right words, structuring, organizing, editing, correcting, and rewriting – require a very different kind of attention.

Proofreading requires very focused, detail-oriented attention, while choosing which words to put down in the first place might require a more open, free-floating attention. When looking for interesting connections between notes, we often need to be in a playful, curious state of mind, whereas when putting them in logical order, our state of mind probably needs to be more serious and precise.

The slip-box is the host of the process outlined above. It provides a place where distinct batches of work can be created, worked on, and saved permanently until the next time we are ready to deploy that particular kind of attention. It deliberately puts distance between ourselves and what we’ve written, which is essential for evaluating it objectively. It is far easier to switch between the role of creator and critic when there is a clear separation between them, and you don’t have to do both at the same time.

By standardizing and streamlining both the format of our notes and the steps by which we process them, the real work can come to the forefront: thinking, reflecting, writing, discussing, testing, and sharing. This is the work that adds value, and now we have the time to do it more effectively.

Principle #6: Our work only gets better when exposed to high-quality feedback

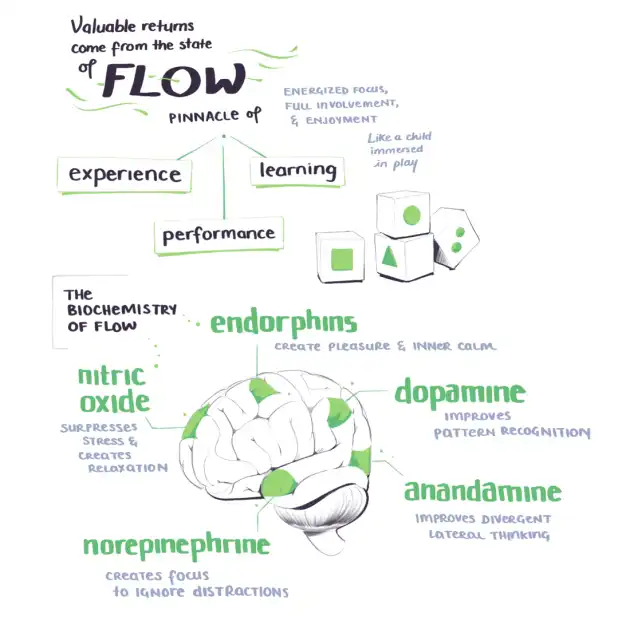

A workflow is similar to a chemical reaction: It can feed on itself, becoming a virtuous cycle where the positive experience of understanding a text motivates us to take on the next task, which helps us get better at what we’re doing, which in return makes it more likely for us to enjoy our work, and so on.

Nothing motivates us more than becoming better at what we do. And we can only become better when we intentionally expose our work to high-quality feedback.

There are many forms of feedback, both internal and external – from peers, from teachers, from social media, and from rereading our own writing. But notes are the only kind of feedback that is available anytime you need it. It is the only way to deliberately practice your thinking and communication skills multiple times per day.

It is easy to think we understand a concept until we try to put it in our own words. Each time we try, we practice the core skill of insight: distinguishing the bits that truly matter from those that don’t. The better we become at it, the more efficient and enjoyable our reading becomes.

Feedback also helps us adjust our expectations and predictions about how much we can get done in an hour or a day. Instead of sitting down to the amorphous task of “writing,” we dedicate each working session to concrete tasks that can be finished in a reasonable timeframe: Write three notes, review two paragraphs, check five sources for an essay, etc. At the end of the day, we know exactly how much we accomplished (or didn’t accomplish) and can adjust our future expectations accordingly.

Principle #7: Work on multiple, simultaneous projects

It is only when you have multiple, simultaneous projects and interests that the full potential of an external thinking system is realized.

Think of the last time you read a book. Perhaps you read it for a certain purpose – to gain some familiarity with a topic you’re interested in or find insights for a project you’re working on. What are the chances that the book contains only the precise insights you were looking for, and no others? Extremely low it would seem. We encounter a constant stream of new ideas, but only a tiny fraction of them will be useful and relevant to us at any given moment.

Since the only way to find out which insights a book contains is to read it, you might as well read and take notes productively. Spending a little extra time to record the best ideas you encounter – whether or not you know how they will ultimately be used – vastly increases the chances that you will “stumble upon” them in the future.

The ability to increase the chances of such future accidental encounters is a powerful one, because the best ideas are usually ones we haven’t anticipated. The most interesting topics are the ones we didn’t plan on learning about. But we can anticipate that fact and set our future selves up for a high probability of productive “accidents.”

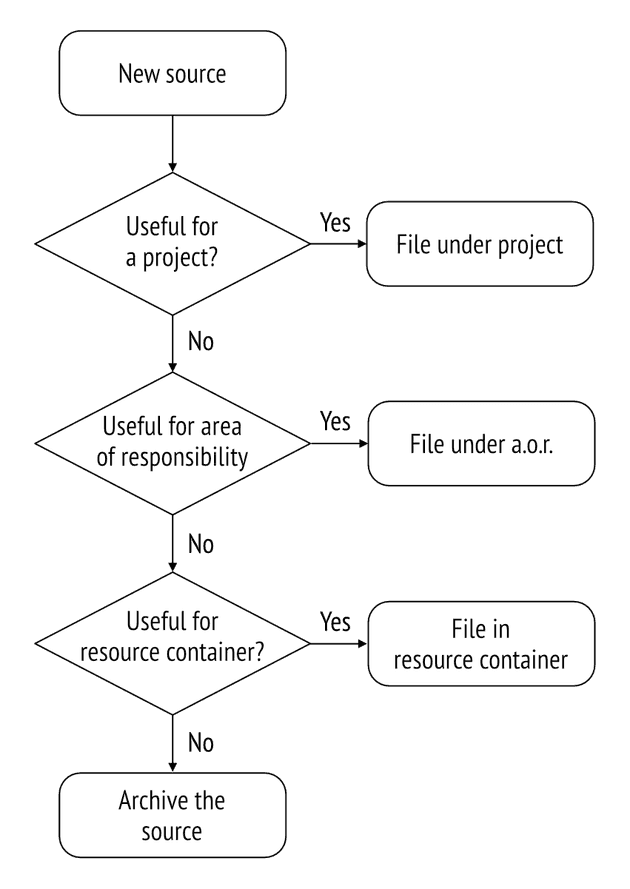

Principle #8: Organize your notes by context, not by topic

The classic mistake is to organize them into ever more specific topics and subtopics. This makes it look less complex, but quickly becomes overwhelming. The more notes pile up, the smaller and narrower the subtopics become, limiting your ability to see meaningful connections between them. With this approach, the greater one’s collection of notes, the less accessible and useful they become.

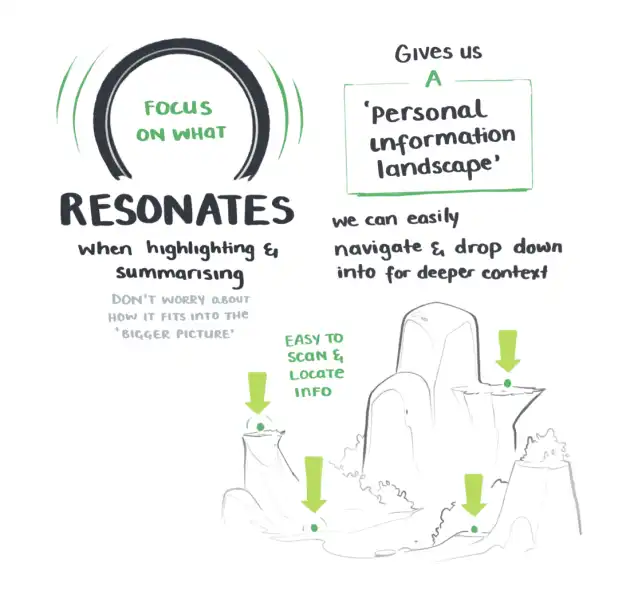

Instead of organizing by topic and subtopic, it is much more effective to organize by context. Specifically, the context in which it will be used. The primary question when deciding where to put something becomes “In which context will I want to stumble upon this again?”

In other words, instead of filing things away according to where they came from, you file them according to where they’re going. This is the essential difference between organizing like a librarian and organizing like a writer.

A librarian asks “Where should I store this note?” Their goal is to maintain a taxonomy of knowledge that is accessible to everyone, which means they have to use only the most obvious categories. They might file notes on a psychology paper under “misjudgments,” “experimental psychology,” or “experiments.”

That works fine for a library, but not for a writer. No pile of notes filed uniformly under “psychology” will be easy to turn into a paper. There is no variation or disagreement from which an interesting argument could arise.

A writer asks “In which circumstances will I want to stumble upon this note?” They will file it under a paper they are writing, a conference they are speaking at, or an ongoing collaboration with a colleague. These are concrete, near-term deliverables and not abstract categories.

Organizing by context does take a little bit of thought. The answer isn’t always immediately obvious. A book about personal finance might interest me for completely different reasons if I am a politician working on a campaign speech, a financial advisor trying to help a client, or an economist developing monetary policy. If I encounter a novel engineering method, it may be useful for completely different reasons depending on whether I am working on an engineering textbook, a skyscraper, or a rocket booster.

Writers don’t think about a single, “correct” location for a piece of information. They deal in “scraps” which can often be repurposed and reused elsewhere. The discarded byproducts from one piece of writing may become the essential pillars of the next one. The slip-box is a thinking tool, not an encyclopedia, so completeness is not important. The only gaps we do need to be concerned about are the gaps in the final manuscript we are working toward.

By saving all the byproducts of our writing, we collect all the future material we might need in one place. This approach sets up your future self with everything they need to work as decisively and efficiently as possible. They won’t need to trawl through folder after folder looking for all the sources they need. You’ll already have done that work for them.

Principle #9: Always follow the most interesting path

Ahrens notes that in most cases, students fail not because of a lack of ability, but because they lose a personal connection to what they are learning:

“When even highly intelligent students fail in their studies, it’s most often because they cease to see the meaning in what they were supposed to learn (cf. Balduf 2009), are unable to make a connection to their personal goals (Glynn et al. 2009) or lack the ability to control their own studies autonomously and on their own terms (Reeve and Jan 2006; Reeve 2009).”

This is why we must spend as much time as possible working on things we find interesting. It is not an indulgence. It is an essential part of making our work sustainable and thus successful.

This advice runs counter to the typical approach to planning we are taught. We are told to “make a plan” upfront and in detail. Success is then measured by how closely we stick to this plan. Our changing interests and motivations are to be ignored or suppressed if they interfere with the plan.

The history of science is full of stories of accidental discoveries. Ahrens gives the example of the team that discovered the structure of DNA. It started with a grant, but not a grant to study DNA. They were awarded funds to find a treatment for cancer. As they worked, the team followed their intuition and interest, developing the actual research program along the way (Rheinberger 1997). If they had stuck religiously to their original plan, they probably wouldn’t have discovered a cure for cancer and certainly wouldn’t have discovered the structure of DNA.

Plans are meant to help us feel in control. But it is much more important to actually be in control, which means being able to steer our work towards what we consider interesting and relevant. According to a 2006 study by psychology professor Arlen Moller, “When people experienced a sense of autonomy with regard to the choice [of what to work on], their energy for subsequent tasks was not diminished” (Moller 2006, 1034). In other words, when we have a choice about what to work on and when, it doesn’t take as much willpower to do it.

Our sense of motivation depends on making consistent forward progress. But in creative work, questions change and new directions emerge. That is the nature of insight. So we don’t want to work according to a rigid workflow that is threatened by the unexpected. We need to be able to make small, constant adjustments to keep our interest, motivation, and work aligned.

By breaking down the work of writing into discrete steps, getting quick feedback on each one, and always following the path that promises the most insight, unexpected insights can become the driving force of our work.

Luhmann never forced himself to do anything and only did what came easily to him: “When I am stuck for one moment, I leave it and do something else.” As in martial arts, if you encounter resistance or an opposing force, you should not push against it but instead redirect it towards another productive goal.

Principle #10: Save contradictory ideas

Working with a slip-box naturally leads us to save ideas that are contradictory or paradoxical.

It’s much easier to develop an argument from a lively discussion of pros and cons rather than a litany of one-sided arguments and perfectly fitting quotes.

Our only criterion for what to save is whether it connects to existing ideas and adds to the discussion. When we focus on open connections, disconfirming or contradictory data suddenly becomes very valuable. It often raises new questions and opens new paths of inquiry. The experience of having one piece of data completely change your perspective can be exhilarating.

The real enemy of independent thinking is not any external authority, but our own inertia. We need to find ways to counteract confirmation bias – our tendency to take into account only information that confirms what we already believe. We need to regularly confront our errors, mistakes, and misunderstandings.

By taking notes on a wide variety of sources and in objective formats that exist outside our heads, we practice the skill of seeing what is really there and describing it plainfully and factually. By saving ideas that aren’t compatible with each other and don’t necessarily support what we already think, we train ourselves to develop subtle theories over time instead of immediately jumping to conclusions.

By playing with a concept, stretching and reconceiving and remixing it, we become less attached to how it was originally presented. We can extract certain aspects or details for our own uses. With so many ideas at our disposal, we are no longer threatened by the possibility that a new idea will undermine existing ones.

Working with a slip-box can be disheartening, because you are constantly faced with the gaps in your understanding. But at the same time, it increases the chances that you will actually move the work forward.

Students in most educational institutions are not encouraged to independently build a network of connections between different kinds of information. They aren’t taught how to organize the very best and most relevant knowledge they encounter in a long-term way across many topics. Most tragically of all, they aren’t taught to follow their interests and take the most promising path in their research.

Ultimately, learning should not be about hoarding stockpiles of knowledge like gold coins. It is about becoming a different kind of person with a different way of thinking. The beauty of this approach is that we co-evolve with our slip-boxes: We build the same connections in our heads as we deliberately develop them in our slip-box. Writing then is best seen not only as a tool for thinking but as a tool for personal growth.

The 8 Steps of Taking Smart Notes

Ahrens recommends the following 8 steps for taking notes:

- Make fleeting notes

- Make literature notes

- Make permanent notes

- Now add your new permanent notes to the slip-box

- Develop your topics, questions and research projects bottom up from within the slip-box

- Decide on a topic to write about from within the slip-box

- Turn your notes into a rough draft

- Edit and proofread your manuscript

He notes that Luhmann actually had two slip-boxes: the first was the “bibliographical” slip-box, which contained brief notes on the content of the literature he read along with a citation of the source; the second “main” slip-box contained the ideas and theories he developed based on those sources. Both were wooden boxes containing paper index cards.

Luhmann distinguished between three kinds of notes that went into his slip-boxes: fleeting notes, literature notes, and permanent notes.

-

Make fleeting notes

- Fleeting notes are quick, informal notes on any thought or idea that pops into your mind. They don’t need to be highly organized, and in fact shouldn’t be. They are not meant to capture an idea in full detail, but serve more as reminders of what is in your head.

-

Make literature notes

-

The second type of note is known as a “literature note.” As he read, Luhmann would write down on index cards the main points he didn’t want to forget or that he thought he could use in his own writing, with the bibliographic details on the back.

-

Ahrens offers four guidelines in creating literature notes:

- Be extremely selective in what you decide to keep

- Keep the overall note as short as possible

- Use your own words, instead of copying quotes verbatim

- Write down the bibliographic details on the source

-

-

Make permanent notes

-

Permanent notes are the third type of note, and make up the long-term knowledge that give the slip-box its value.

-

This step starts with looking through the first two kinds of notes that you’ve created: fleeting notes and literature notes. Ahrens recommends doing this about once a day, before you completely forget what they contain.

-

As you go through them, think about how they relate to your research, current thinking, or interests. The goal is not just to collect ideas, but to develop arguments and discussions over time. If you need help jogging your memory, simply look at the existing topics in your slip-box, since it already contains only things that interest you.

-

Here are a few questions to ask yourself as you turn fleeting and literature notes into permanent notes:

- How does the new information contradict, correct, support, or add to what I already know?

- How can I combine ideas to generate something new?

- What questions are triggered by these new ideas?

-

As answers to these questions come to mind, write down each new idea, comment, or thought on its own note. If writing on paper, only write on one side, so you can quickly review your notes without having to flip them over.

-

Write these permanent notes as if you are writing for someone else. That is, use full sentences, disclose your sources, make explicit references, and try to be as precise and brief as possible.

-

Once this step is done, throw away (or delete) the fleeting notes from step one and file the literature notes from step two into your bibliographic slip-box.

-

-

Add your permanent notes to the slip-box

-

It’s now time to add the permanent notes you’ve created to your slip-box. Do this by filing each note behind a related note (if it doesn’t relate to any existing notes, add it to the very end).

-

Optionally, you can also:

- Add links to (and from) related notes

- Adding it to an “index” – a special kind of note that serves as a “table of contents” and entry point for an important topic, including a sorted collection of links on the topic

-

Each of the above methods is a way of creating an internal pathway through your slip-box. Like hyperlinks on a website, they give you many ways to associate ideas with each other. By following the links, you encounter new and different perspectives than where you started.

-

Luhmann wrote his notes with great care, not much different from his style in the final manuscript. More often than not, new notes would become part of existing strands of thought. He would add links to other notes both close by, and in distantly related fields. Rarely would a note stay in isolation.

-

-

Develop your topics, questions, and research projects bottom up from within the slip-box

-

With so many standardized notes organized in a consistent format, you are now free to develop ideas in a “bottom up” way. See what is there, what is missing, and which questions arise. Look for gaps that you can fill through further reading.

-

If and when needed, another special kind of note you can create is an “overview” note. These notes provide a “bird’s eye view” of a topic that has already been developed to such an extent that a big picture view is needed. Overview notes help to structure your thoughts and can be seen as an in-between step in the development of a manuscript.

-

-

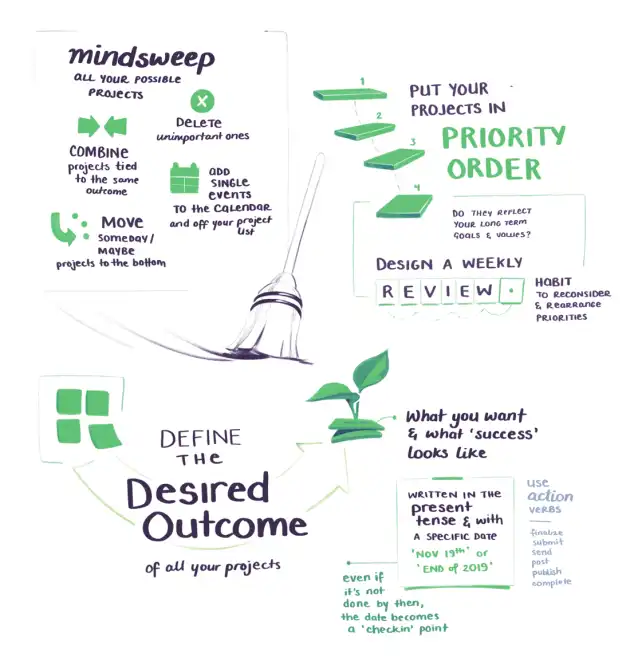

Decide on a topic to write about from within the slip-box

- Instead of coming up with a topic or thesis upfront, you can just look into your slip-box and look for what is most interesting. Your writing will be based on what you already have, not on an unfounded guess about what the literature you are about to read might contain. Follow the connections between notes and collect all the relevant notes on the topic you’ve found.

-

Turn your notes into a rough draft

- Don’t simply copy your notes into a manuscript. Translate them into something coherent and embed them into the context of your argument. As you detect holes in your argument, fill them or change the argument.

-

Edit and proofread your manuscript

-

From this point forward, all you have to do is refine your rough draft until it’s ready to be published.

-

This process of creating notes and making connections shouldn’t be seen as merely maintenance. The search for meaningful connections is a crucial part of the thinking process. Instead of figuratively searching our memories, we literally go through the slip-box and form concrete links. By working with actual notes, we ensure that our thinking is rooted in a network of facts, thought-through ideas, and verifiable references.

-

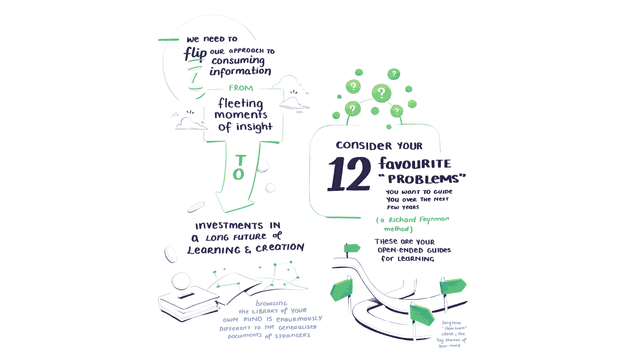

how to find your 12 favorite problems

-

Make a list of the areas of your life. These will serve as your backbone for your later thinking.

-

Use an outline or mind map as a creative technique. You can use any creative technique. Now it is only a matter of producing for the time being. Collect all problems and possible projects that seem interesting to you in some way. Sort everything into groups. Try to find patterns.

-

Throw out everything that does not inspire you.

-

This method is only a suggestion! All good methods follow these two meta-rules:

- Collect first without judging.

- Then sift out the gold pieces.

-

Particularly relevant favorites are your life goals! Need help finding your favorites? Make a list of all your life goals. Which of your collected problems and projects are especially relevant to your life goals? The more important a life goal is to you, the more the problems and projects related to it inspire you.

-

As a knowledge worker, you have it easy! The field of “job and career” can produce a large number of darlings. After all, your profession is to deal with problems or knowledge-based projects.

-

potential problems?

- How can I strengthen all my relationships?

- How do I be a better father, son, brother, and friend?

- How do we provide a claims experience that feels like magic such as traveling, life experiences, food, etc…?

- how do we measure performance, critical workflows, extracting data, KPI, etc… out of system effectively?

- how can I connect with my children better?

- -How do we leverage AI to troubleshoot and solve customer problems?-

- -How do we pre-empt customer problems before they happen?-

- what’s the most effective way to learn and share agile technical practices?

- how do I learn, develop, and maintain system effectively with teams?

- How do identify the most important books on every topic and organize them in a way that provides a clear learning path to all learners?

- how to generate wealth effectively through investing, full-time employee, real estate, business, etc…?

- How can I enjoy life while still building big and important things (how can solving problems and building companies not consume me?)

- How do I get the right quality filters so that I focus on the right things but not miss out on serendipity/new ideas?

- what does it mean to be learning organization?

- how to find undervalued companies that have high competitive advantage and high margin of safety?

- what business/industry that I would be interested in learning more about?

- how do I balance between work, health, interests, family effectively?

- how do I manage my emotions effectively and intelligently?

- how do I manage/organize my knowledge effectively?

How to choose a note-taking method

-

Technology, particularly recently, has transformed note-taking from a static to an interactive exercise. With new tools like AI and backlinking, we’re interacting with our notes in ways that were previously impossible. This evolution is happening at a faster rate now than ever before.

Traditional note-taking methods – adapted for 2023

The Outline note-taking method

-

You probably remember learning the Outline method in school. The simplicity makes it a great place to start if you’re trying to get in the habit of taking better notes. It involves creating a structured, hierarchical form of notes using indentation to denote different points, sub-points, and details. You’ll want to make sure your note-taking app handles lists well for this.

-

How to take notes using the Outline method:

- Start by writing the main topic at the top of the page.

- Below the main topic, write the main supporting points using numbers or Roman numerals.

- Below each main point, write sub-points using bullets. Indent these slightly to the right.

- If there are additional details related to a sub-point, list these under the corresponding bullet. You can denote these with letters or symbols if that helps make it easier to read.

- Continue this pattern as necessary.

- template for outlining method

💡

The Charting Method

- If you find the Outlining method a bit dull (or have PTSD from school),one step down is the Charting note-taking method. It’s useful for information that fits well into categories.

- How to take notes using the Charting method

- Start by identifying categories relevant to the information you’re taking notes on.

- List out headings on the note with a category and create it as a backlink.

- As you receive or read information, fill in the relevant details under the corresponding category in the chart.

- Go through and organize/re-order the points.

- If your note-taking app allows it, it can be useful to pull them up side by side to compare and contrast topics.

- template of the charting note-taking method

The Cornell Method of taking notes

- How to take Cornell Notes in a digital note-taking app:

- Create a note and give it a title. Divide the note into three sections: Cue, Notes and Summary. Make each one a heading that you can take notes under.

- Take notes in the “Notes” section while learning, reading or brainstorming.

- Afterwards, fill out the “Cues” section of your note with questions or keywords that relate to the notes. This is a great place to add tags if your note-taking app allows.

- Summarize the main points under “Summary” to quickly access the information later.

- template of the Cornell method of note-taking.

The Mapping Method of note-taking

- How to do the traditional Mapping method:

- Start by writing the main idea in the center of your paper.

- Draw branches from the main idea to the main supporting points or themes.

- From each supporting point, draw additional branches to related sub-points or details.

- You can use different colors, symbols, and illustrations to help visually differentiate and organize ideas.

- If you have a networked note-taking app, you don’t need to worry about drawing or making connections. Just create backlinked notes, and you’ll see how they are all interconnected. In apps like Reflect the supporting points will be pulled in automatically

💡

SQ3R Method of note-taking

- Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review.

- How to take notes using the SQ3R method

-

Survey: Skim the material to get an overall picture. Look at headings, subheadings, and highlighted words. No note-taking yet!

-

Question: Before you start reading, ask yourself questions based on your initial survey. What do you expect to learn? Write these down.

-

Read: Now read the material carefully, looking for answers to your questions and creating new ones.

-

Recite: After reading a section, try to recite the main points and answer your questions from memory into your notes. Then check the text to see if you were correct.

-

Review: After you’ve finished reading, review your notes. This reinforces what you’ve learned.

-

Modern Note-Taking Methods

Daily Journaling method of note-taking

-

Daily Journaling involves having an ongoing Daily Note from where you base all of your note-taking from. Each day has a new page in the ongoing note where everything in your day goes. Each element is backlinked out to a page where you can provide more information.

-

The Daily Journaling method is more suited for overall knowledge capture than a method for studying a specific topic. With backlinking, it’s a great way to build up a second brain over time.

-

How to apply the Daily Journaling method to your notes:

-

Create an ongoing note. If you use a note-taking app that uses the Daily Note format, you won’t need to do this step. It will already be created for you.

-

Each day, create a page with the date on top (also backlinked).

-

In each day’s note, start by writing everything that happens. Backlink all people, places, things and ideas you have. Record your meeting notes. Write your to-do list items. Everything!

-

Easily search and find things. Because your notes are filled with backlinks, you’ll be able to make new associations. You’ll also know exactly what you did on each day.

-

If future to-do items come up, write them in the daily note in the future.

-

You can watch a video on how to setup a daily Reflection in your notes here.

-

The Zettelkasten note-taking method

- How to take notes through networked note-taking (i.e. the Zettelkasten method):

-

Create a new note for each Idea: Whenever you encounter an idea you want to remember, create a new note. The note should be self-contained, so it can be understood without referring to any other note.

-

Write the note in your own words: Don’t simply copy and paste from your source. Write the note in your own words to aid comprehension and retention.

-

Give the note a unique identifier: Each note needs a unique identifier to make it easy to refer to.

-

Link your notes together: When you write a note related to a previous one, create a link from one to the other. This creates a network of interconnected ideas, rather than a hierarchy.

-

Create an index note: Having an index note provides a high-level overview of your notes and their connections. This can be organized by topic, by date, or in another way that makes sense to you.

-

Regularly review your notes: The Zettelkasten method is designed to be an ongoing conversation with yourself. Regularly review your notes, add new ones, and build new connections.

-

Use tags or keywords: Tags can help group related notes together, making them easier to search for and find. They can also show up in backlinking, further strengthening the network of related notes.

-

You can watch a video of how to easily apply the Zettelkasten method -> Video preview

-

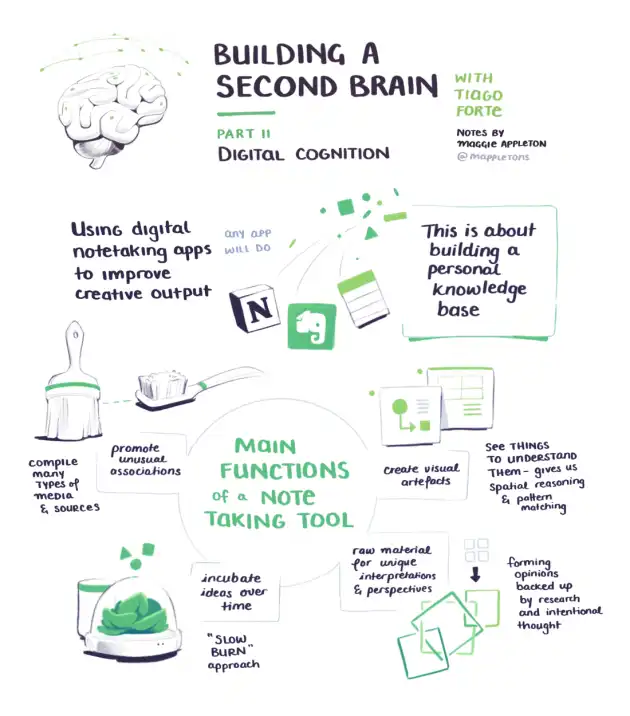

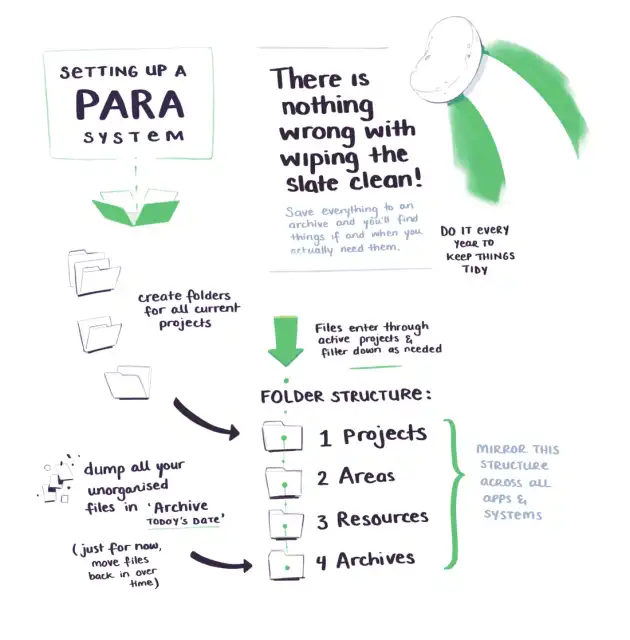

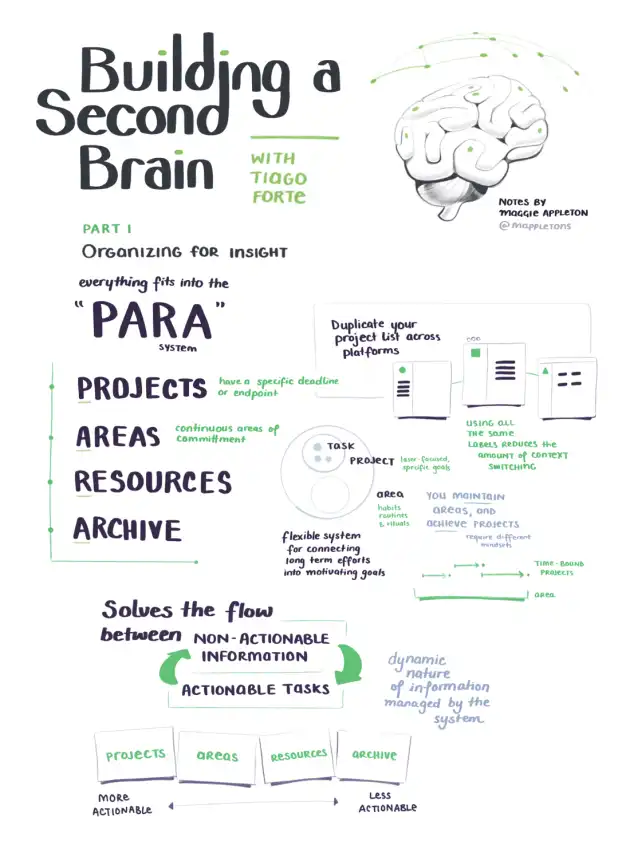

Tiago Forte’s PARA method (from Building a Second Brain)

-

PARA is a key component of Tiago Forte’s “Building a Second Brain” methodology. The acronym PARA stands for: Projects, Areas, Resources and Archives.

-

Projects: A project is defined as a series of tasks linked to a goal, with a deadline. You can create a separate note or folder for each project you are currently working on. Each of these should be something that you can feasibly complete in the near future. If your note-taking app supports it, you can give it a PARA tag.

-

Areas: Areas of responsibility are parts of your life that need continuous maintenance and oversight, without a specific end date. Examples could include health, finance, career, or relationships. You can create a note or folder for each area and add relevant information as you come across it.

-

Resources: Resources are topics of ongoing interest that you reference often. These could include anything from personal interests (like photography or cooking) to professional skills (like marketing or data analysis). Resources don’t have specific outcomes or deadlines attached to them, but they’re topics you consistently return to and learn about over time.

-

Archives: Anything that no longer falls into the above categories can be moved into Archives. This keeps your current system clean and focused, while still maintaining a record of past projects and interests.

-

Here’s how you might use PARA in Reflect, for example.

-

Projects: Create a back-linked note called “Projects”. Inside, make additional back-linked notes for each of your current projects. Each note should contain all the relevant information for its corresponding project.

-

Areas: Make another note called “Areas”. Again, create a separate note for each area of your life that requires continuous maintenance. These notes should contain relevant information, tasks, and observations about their respective areas.

-

Resources: Create a “Resources” note where you’ll make separate notes or pages for each topic of ongoing interest. You can add to these notes over time as you learn more about each topic.

-

Archives: Finally, create an “Archives” note. When a project is complete, move its note from the “Projects” notebook to “Archives”. Do the same for areas and resources that are no longer active.

-

Evergreen Notes

- How to apply the Evergreen note-taking method:

- Create atomic notes: Each note should contain a single idea or concept that you want to remember or think about further. Keep it concise and self-contained.

- Develop full thoughts: Don’t just jot down ideas or facts. Expand them into complete sentences or paragraphs that reflect your understanding of the topic.

- Link notes: Whenever you create a new note that’s related to a previous one, create a link between them. This forms a network of thoughts and ideas that are easy to navigate.

- Regularly review and revise: This isn’t a “set it and forget it” system. Regularly look back over your notes, update them with new insights, and ensure that they’re as valuable as possible.

- Avoid transient information: Evergreen notes are meant to be long-lasting and always valuable. Avoid including information that will quickly become outdated or irrelevant.

- You can view a template to use for the Evergreen note-taking method here.

Bullet Journaling

- How to apply to Bullet Journaling method to your notes:

- Index: This is essentially your table of contents. Create a note or a page at the beginning of your journal where you’ll keep track of where everything else is.

- Future Log: This is a place for events or tasks that are happening in the future, beyond the current month. You can create a note or page for each month or create a single note with different sections for each month.

- Monthly Log: At the beginning of each month, create a new note. On one side, write down all the days of the month and next to them write any events or tasks happening on those days. On the other side, write down your tasks for the month.

- Daily Log (or Daily Note): Each day, create a new note or section within your Monthly Log. Here you’ll use the bullet journal symbols to keep track of tasks (•), events (O), and notes (—).

- Collections: These are notes or pages on specific topics that you want to keep track of. They can be anything from books you want to read, to project ideas, to shopping lists. Create a new note for each collection and remember to add it to your Index.

- Migration: At the end of each month, look over your tasks. Any that weren’t completed either need to be “migrated” forward to the next month (if they’re still important) or crossed out (if they’re no longer relevant).

💡

- See templates for the Bullet Journaling method here.

AI-Powered note-taking

- How to take notes with AI

- Tools like Reflect that use Whisper can transcribe speech in real time with human level accuracy. See how to do this here.

- Using GPT-4, you can do all kinds of things with text in your notes:

- Create summaries from text

- List key takeaways and action items from your notes

- Rephrase your writing in the tone of another author

- Conduct research and gather information

- Translate things into another language

- Have AI come up with counter examples or factual evidence

- Have the AI act as a copy editor

- Get a working Executive Assistant in your notes

- You can actually combine these features as well.

- For example, you could ramble about a topic you are interested in, have the AI turn it into an article outline that you can edit and then write around. After writing you can have the AI assistant rephrase parts you don’t like to get the perfect article.

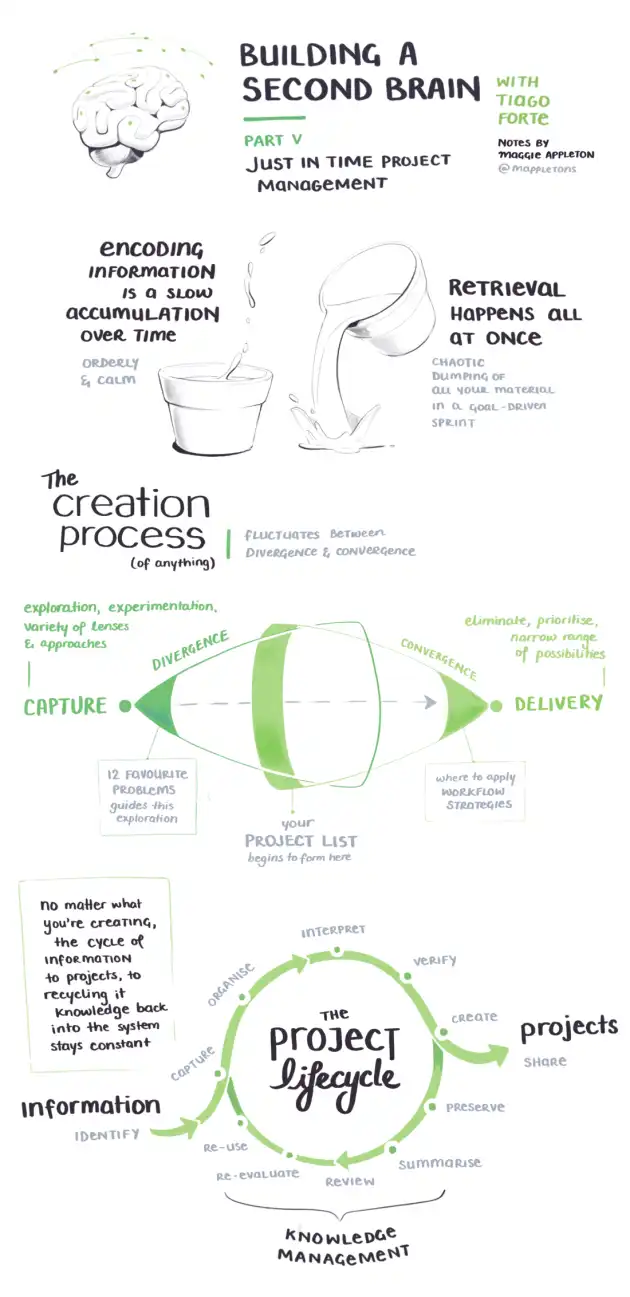

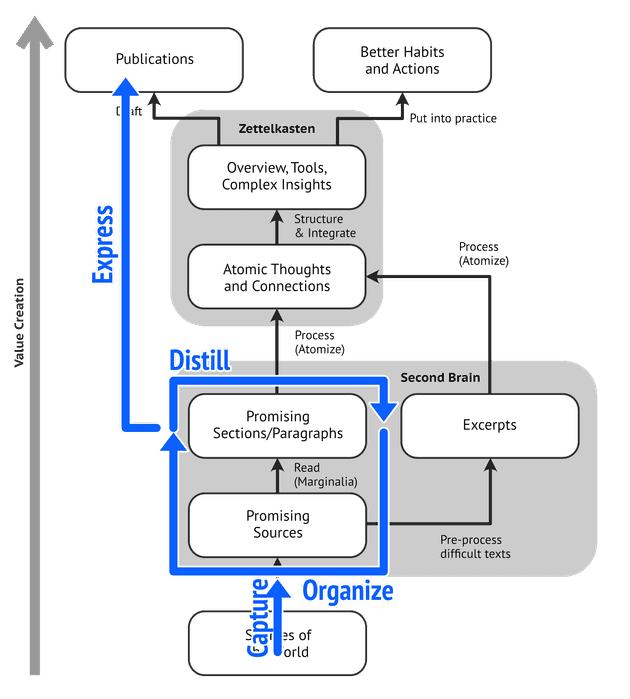

how does BSAB work?

-

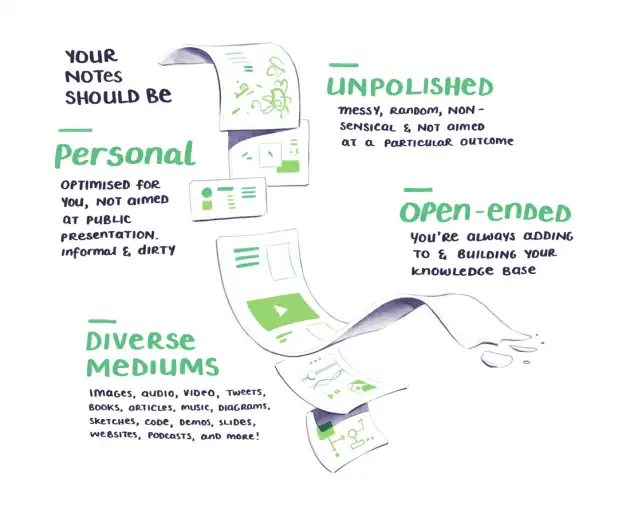

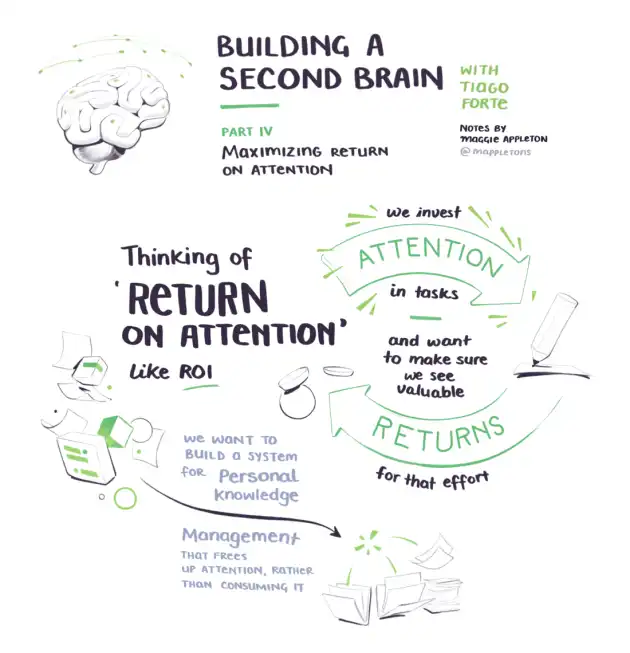

Building a Second Brain is an information management system. Processing of sources is not the focus of the system, nor is the way of processing information an essential part of the system. Even the processing method Forte proposes, the progressive summarization is not a processing method of information, but a preparation method of resources like articles, podcasts, and books for later use. BASB’s strengths lie in the management of sources of knowledge.

- While BASB’s “second brain” doesn’t move beyond the resource, the work with the Zettelkasten begins only after we have extracted the ideas and thoughts from the resource and put each of them on an atomic note while leaving behind the resource. This is one of the main differences between BASB and the ZKM. BASB is a system for resource management; ZKM is a method for working with ideas themselves.

-

Building a Second Brain is a project management system. The emphasis of the whole system on action effectiveness is particularly evident through the filing system PARA.(6) The four parts (Projects, Areas, Rresources, Archive) are aligned to a hierarchy of urgency. At the same time, a connection is made between urgency and importance because completed projects are “the blood flow of your Second Brain.”(7) Importance and urgency are the categories of projects and tasks. In a sense, the overall system speaks the “language of action”.

-

In contrast, the Zettelkasten Method speaks the “language of knowledge”. In the Zettelkasten, there is no such thing as importance or urgency. Each note merely contains ideas and their connections to other ideas. Their actionability is a second layer that we put onto them.

-

BASB is for people who want to manage their information streams and resources in a project-oriented way. But probably the most important target group is people who feel overwhelmed by uncertain tasks and modern information overload.

-

In my experience, there are two main types of overload that can be related to the two components of the temperament characteristic of openness.

-

Overload because of Openness to Experience. Formulated as a belief set, the trait Openness to experience would read: What is new is most likely good. Because we live in an age of information inflation,(8) we are inundated with newness. People with a high Openness to Experience live in an information land of milk and honey. But people in the Land of Cockaigne are not happy. They are overstuffed and overwhelmed. They don’t know what to do with themselves. And those who don’t know what to do feel anxiety.(9) You could compare people with a high Openness to Experience to people who have a particularly strong susceptibility to fast food and sweets. Both tend to engage in erratic behaviour, which in turn can lead to anxiety-generating lifestyles.

-

Overload because of Intellect. Formulated as a belief set, the trait intellect would read: Something is interesting if it is a thing that can be studied. These people love to analyze and construct. These are the ones who get lost in analyzing and constructing a perfect system. They run the risk of doing more work on their system than using it for its intended purpose. They can become overwhelmed by a self-created information overload as they build an elaborate system of RSS feeds, web clippers, and other techniques of capturing information and information resources. But they also run the risk of conducting purposeless research, neglecting project- and deadline-oriented work.

-

-

BASB can provide the solution for both types of overload:

- It allows managing information and resources with little effort. This helps people who feel overwhelmed with the overabundance of information and resources.

- It is explicitly project-oriented. This helps people who lose sight of project-oriented work because they are so interested in the matter at hand.

-

Like any management system, BASB consists of three components:

- The System. How are the folders, files, inboxes, etc. arranged?

- The Workflow. How do the resources become the desired end result?

- The Habits. What are the regularly recurring actions needed to take to make the system work and be maintained?

The system - PARA

-

PARA is the storage system of BASB. The acronym stands for the four containers Projects, Areas, Resources and Archive.

-

In most programs, you’d create a folder for each container. However, in some programs there are no folders. Therefore, I usually speak of “containers”. However, I understand PARA as a manifestation of a general principle of self-organization: the iceberg principle of self-organization. I will describe this in more detail towards the end.

-

Projects are short-term efforts in work and personal life. They are what you are currently working on. They have characteristics conducive to work:

-

A beginning and an end (unlike a hobby or an area of responsibility).

-

A concrete result to be achieved and consist of concrete steps that are necessary and together sufficient to achieve that goal. Example: Achieve 100 kilos in the bench press.

-

Areas (of Responsibility) are concerned with anything that you want to keep in mind for the long term. They differ from projects in that you do not pursue a goal with them, but want to maintain a standard. Accordingly, they are not limited in time. One could say that they represent an aspiration on ourselves and our living world. Example: Health and Fitness.

-

Resources are topics that might become relevant or useful at best in the long run.(14) They are a catch-all container for everything that is neither a project nor a responsibility. Resources are:

- topics that are interesting,

- subjects to be researched,

- useful information for later use,

- hobbies. (Note: I consider hobbies to be an area of responsibility because hobbies also have standards). Example: A workout plan to try at some point.

-

The Archive is for everything inactive from the above three categories. It is a storage for things finished and postponed. Example: An old training plan.

-

The four containers are sorted by action relevance:

- Projects are most relevant to action because you are currently working on them and have a deadline. The fact that you have to have a deadline is not the deciding factor, only that you are actively working on them. My personal criterion for this is that I sit down at least once a week to work on the project.

- Areas of responsibility have a longer time horizon and are therefore not immediately relevant for action.

- Resources become actionable only in specific contexts.(25)

- Archived stuff is inactive until it is needed.(26) Therefore, it is hardly relevant to action.

-

This four-folder system is kept simple for a reason: Complex systems usually require complex maintenance. PARA abandons this complexity. CODE, BASB’s workflow, is similarly kept simple.

The workflow - CODE

-

The BASB workflow is divided into four steps:

- Capture includes everything you fill your inboxes with.

- Organise means filing in the PARA folder system.

- Distill means processing of resources with the method of progressive summarizing.

- Express means the application or publication of content.

-

Organize is the step where we empty the inbox and incorporate the resources into the PARA system. In doing so, we use the hierarchical nature of PARA: We first check if the resource can be used for something urgent and then work our way to less urgent:(27)

-

Go through all active projects first. Is the resource useful for the project? If yes, file it under this project.

- If not: Is the resource useful for an area of responsibility? If yes, file it under this area of responsibility

- If not: Is the resource useful as part of a resource container? If yes, file it under the respective resource container.

- If not: Archive the resource.

-

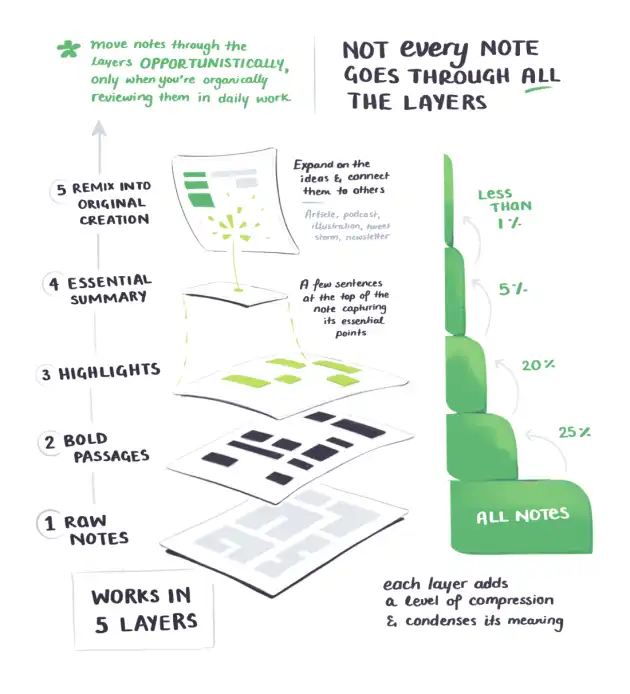

Distill describes the way the resource is processed. Here, Forte recommends the progressive summary:(28)

- Acquisition is counted as the first step of processing. That is: the resource is filed. In Forte, this is already achieved at capture. However, I think it is better to assign this step to Organise. Only when we have filed the resource in the PARA system can we speak of a first edit.

- Read the resource and mark in bold the passages that catch our eye.

- Highlight what seems to be extra important from what is already marked in bold.

- The last step would be the executive summary. This means that you list the most important key points of the resource at the beginning of the document.

-

With BASB, we get stuck with managing resources because we don’t move beyond the resource. Yet, the method of resource editing is quite easily interchangeable. Even if we process the resource to the point of extracting out each individual thought, as is the case with, let’s say, the Zettelkasten Method, we could still fit the individual thoughts into the PARA system as well. So, progressive summarization is not at all an essential ingredient for BASB to work.

- Don’t worry about analyzing, interpreting, or categorizing each point to decide wether to highlight it. That is way too taxing and will break the flow of your concentration. Instead, rely on your intuition to tell you when a passage is interesting, counterintuitive, or relevant to your favorite problems or current project.

-

But the progressive summary is in the spirit of a way of working: The progressive summary could almost be seen as a technique for not letting knowledge work distract you from a project-oriented way of working. We will see more about this in the comparison of BASB and the ZKM. Progressive summarization does not involve thorough extracting and processing of ideas.

-

Express means that Forte encourages us to actually use our system for something. Forte gives some tips in this section such as breaking up larger projects into small steps that are easy to work through.(30) But this step is already outside the actual system of processing and management because most likely you will start writing in your dedicated writing app or implement behavioral changes in your life and not in your second brain.

The Key Habits

-

System-relevant habits are actions that are necessary for the effectiveness of the system, and therefore must be done regularly. As with all project and task management systems, there are two types of habits.

-

Habits of good use of the system. Through these habits, one derives maximum benefit from the system. In BASB, these are the project checklists.

-

Habits of maintenance of the system. By these habits one repairs the current damages and signs of wear. In BASB, these are the reviews.

The Project Checklists

-

There are two checklists: one at the beginning of the project and the other at the end of the project. The checklist at the beginning of the project is for using the system to its fullest extent for the current project. The checklist at the end of the project is for using the completed project to improve the system. So, these two checklists are designed as positive feedback loop:

-

Checklist: Project Start

- Collect: Gather your thoughts about the project. What do you already know about it? What don’t you know? What is your goal? What people can you tap into? What are possible resources?

- Review: Search the folders of your second brain for useful information.

- Search: Use the global search to back up the second step. Sometimes, useful information turns up in surprising places.

- Move: Move all relevant notes to the project folder.

- Create: Create an outline from everything you have collected in the project folder.(36) Important: You are only planning the project. You’re not working on it directly yet.

-

Checklist: End of project

- Mark: Mark the project as complete in your task management and still process any loose ends.

- Cross out: Mark the goal associated with the project as achieved and move the goal to a “Achieved” list. You can use this list of achieved goals as motivation.

- Review: Review the project folder for content that you can use for other projects.

- Move: Move the project folder from “Projects” (PARA) to the archive (PARA).

- If project is becoming inactive: If you cancel or postpone the project, make sure you can start where you left off. Create a note, with all the necessary information, how you would continue and also with the reasons why you stopped.(41)

Review

-

All systems get cluttered and deteriorate if they are not maintained. Forte explicitly follows the tradition of David Allen’s GTD here. I consider these checklists to be fairly self-explanatory.

-

Weekly Review

- Empty the email inbox.

- View the calendar.

- Clean up the desk of your computer.

- Empty the inbox of your note-taking software.

- There is no editing involved! This is just about putting the material into the PARA system.

- Choose the assignments for the week.

-

Monthly Review

- View and update your quarterly goals.

- View and update your project list.

- View your areas of responsibility.

- View your “someday/maybes.”

- Update how important and urgent the tasks are.

- So we have all three aspects system, workflow and habits together.

Building a Second Brain and the Zettelkasten Method in comparison

-

Simplified, BASB is a source material feeder system for project-oriented self-organization. It is especially suitable for people whose projects are particularly dependent on source material. Oddly enough, the processing of knowledge seems almost to be considered a necessary evil, to be automated and simplified as much as possible. Thus, Forte writes in the processing step Distill:

-

Don’t worry about analyzing, interpreting, or categorizing each point to decide whether to highlight it. That is way too taxing and will break the flow of your concentration. Instead, rely on your intuition to tell you when a passage is interesting, counterintuitive, or relevant to your favorite problems or current project.(53)

Analysis, interpretation, and classification of resources and the thoughts they contain are essential to the processing of knowledge itself. It could not be clearer: The processing of knowledge, knowledge work, is explicitly not part of BASB. Knowledge work needs to be done, regardless, if you want to actually produce value. So, you will perform the actual knowledge processing outside the BASB system.

- The Zettelkasten Method, on the other hand, is a method for processing knowledge. The analysis of single thoughts and their relations to each other is clearly a centerpiece. Project work, on the other hand, is in the periphery. In a way, the ZKM is agnostic to the use of the processed knowledge. We could spend a lifetime working with a Zettelkasten without publishing a single line of text.

PARA vs Zettelkasten

-

The system PARA is a filing system arranged by time relevance to action. Projects come before areas of responsibility because they have a short to medium time horizon, while areas of responsibility have an unlimited time horizon. Resources and Archives come last because they are usually neither a priority nor urgent.

-

The Zettelkasten Method is based on a hierarchy-free network. There are individual notes and their links. The structure notes can be used to create a hierarchy, but they are rather a just one representation possibility for a set of notes. One can create other structure notes with alternative hierarchies or even some with a non-hierarchical representation. In the Zettelkasten, one’s thoughts find an equal coexistence.

-

BASB speaks the language of action. ZKM speaks the language of knowledge. The basic categories of BASB are importance and urgency. These are categories of action. The basic categories of ZKM are atomic thought and its relation to other thoughts. BASB chooses as its filing categories PARA, a folder system that is a hierarchy of urgency. ZKM is a heterarchy of thoughts that can float freely in the ether like in the Platonic world of ideas.

-

Completed projects are considered the blood supply of the second brain:

I’ve learned that completed creative projects are the blood flow of your Second Brain. They keep the whole system nourished, fresh and primed for action. It doesn’t matter how organized, aesthetically pleasing, or impressive your notetaking [sic!] system is. It is only the steady completion of tangible wins that can infuse you with a sense of determination, momentum, and accomplishment.(56) (Emphasis mine)

-

And last but not least: Progressive summarizing, Forte’s proposed method of processing resources, is just a method of highlighting a text. At no point does it leave behind the resource. Thus, not only is it not processing resources into knowledge, it is merely preparing resources so that they are easier to skim.

-

The restlessness of PARA

- PARA is not based on an assumed correctness of filing (for example, on a sophisticated metaphysics of categories). It is a production system that puts information where it is most likely to be needed. Because this is constantly changing, the whole system is subject to constant upheaval and reordering:

- PARA isn’t a filing system; it’s a production system. It’s no use trying to find the “perfect place” where a note or file belongs. There isn’t one. The whole system is constantly shifting and changing in sync with your constantly changing life.

- Resources and notes have no fixed location, but are always moved to where they seem to make the most sense. If one relates the three active folders (projects, areas of responsibility, resources) to each other, one could say that the internal purpose of the areas of responsibility is to supply the project folder with projects. The metaphor of blood supply that Forte chooses to describe the role of completed projects is perfect: “The blood supply to the brain is of absolute importance. Without blood flow, neurons die within minutes. If the project folder is not supplied with projects, the second brain dies. The central task of the user is to complete the projects and thus return the blood. Otherwise, your brain will suffer from a stroke.

-

My research on psychological entropy is a good example of what BASB is inappropriate for:

-

It took me a few weeks to build up the sections of my Zettelkasten that cover the topic of psychological entropy. In the language of BASB, this was a research project. While I did not have a firm deadline, I had two clear goals. First, I wanted to achieve “Feynmanian clarity.” That is, I wanted to understand the phenomenon to the point where I could explain it to someone without stuttering. Second, I wanted to build the structures so that I could smoothly incorporate new knowledge in the future. I wanted to create a place that seemed like an old acquaintance. The first would still have been compatible with BASB, but the second goal was not.

-

Not only do I have many such research projects. They also span disciplines and years. When I do a research day, I may well combine the results of 5 or 6 such research projects. This means that within hours I have to access knowledge that I have built up over a span of 10–15 years. If the knowledge were spread over folders in my second brain and I was forced to re-collect such amounts of knowledge, my work would not be possible. I would be too slow. If I have an idea, it must be realizable at this moment. I can only do that with my Zettelkasten, but not with the PARA system.

-

Forte recommends relying on system-wide search. But my experience with the Zettelkasten Method has shown me that as the size of the Zettelkasten increases, the search function becomes less reliable and more cumbersome to use. I’m already at the point where the search function has lost much of its usefulness. My Zettelkasten is simply too complex for the search to provide reliable access.

-

-

This problem is by no means only relevant for people like me. It results from the relationship between knowledge and the user. The problem described above always arises when one works at the limits of one’s own cognitive capacities. It is only a matter of time before one reaches this limit when using a system for a lifetime. For some, this point arrives after a few years and for others after 10 years. But one thing is certain: It will arrive.

-

This does not mean that BASB is useless! BASB provides a system for information and project management. It provides tools to meet requirements upstream of resource processing. BASB is something like a combination of forestry system and lumberyard. The Zettelkasten, on the other hand, deals with the actual processing of knowledge.

-

BASB is a hybrid of information management system and project management system. The Zettelkasten Method is a system of creating an integrated thinking environment and working with it.

BASB and ZKM

-

From this graph, we can see that BASB manages exactly what is outside the Zettelkasten. BASB is not about creating a second brain in the direct sense. Rather, it is about handing off to the system all that does not belong in the brain. Again, BASB is in the tradition of GTD and accomplishes the same thing.

-

The system and workflow of BASB and the ZKM are easily compatible. We use BASB for organizing resources and excerpts. Our Zettelkasten serves as our integrated thinking environment. Here we process the collected resources and excerpts into atomic thoughts and link them together.

-

From the PARA system, the Zettelkasten is responsible for both resources and the archive. Projects and areas of responsibility are divided: Content belongs in the Zettelkasten, tasks in the task organisation.

-

The project habits can be easily transferred to ZKM.

-

The routine at the start of the project would look like this:

-

Create a structure note for your project in the Zettelkasten. This is the place where you collect everything. The difference is that you just create links to needed notes instead of moving the actual files. This applies to notes anyway, but also to excerpts and resources in the form of PDFs, books, etc.

-

Collect: Collect everything you know about the project on the structure note.

-

Review: Search your notebook for existing knowledge and refer to it from your project structure sheet.

-

Search: Systematically search all other places. (Like collections of unread PDFs, link lists, etc.)

-

Move: Moving to a project folder is unnecessary. All notes stay where they are.

-

The result is a note that contains all information about the project. It refers to all notes that are relevant for the project. However, it also references resources and excerpts that are outside the Zettelkasten. So, you process everything until you have one structure note that just links to notes and comments on them and their relationships.

-

-

The routine at the end of the project, would look like this:

- Mark and Cross Out are part of task management and have nothing to do with the Zettelkasten.

- Review and Move are already partially done, in extreme cases even completely: After all, you have developed all thoughts in the Zettelkasten. They are already in the Zettelkasten and completely integrated into your base network. For every note you write, you can check directly when you create it whether the note is usable for another project. When you finish the project, there’s one thing you can check: if something came up while you were writing the manuscript that you want to feed back into the Zettelkasten. That’s what I call “processing back.”

- If project becomes inactive is superfluous. Everything is in the Zettelkasten anyway.

-

Quotes

-

Don’t worry about analyzing, interpreting, or categorizing each point to decide whether to highlight it. That is way too taxing and will break the flow of your concentration. Instead, rely on your intuition to tell you when a passage is interesting, counterintuitive, or relevant to your favorite problems or current project. (Emphasis mine)

-

Knowledge work is characterized by the fact that tasks are not given, but must first be recognized as such. This lack of clarity about how to understand something and what to do with it leads to psychological entropy. Then, we feel nervous, uncertain, and anxious.

References

- https://reflect.app/blog/guide_to_note-taking_methods_and_strategies

- https://www.reddit.com/r/PKMS/comments/nfef59/list_of_personal_knowledge_management_systems/

- https://ericsandroni.com/book-summary-building-a-second-brain-by-tiago-forte/

- https://maggieappleton.com/basb

- https://fortelabs.com/blog/basboverview/

- https://www.samuelthomasdavies.com/book-summaries/business/building-a-second-brain/

- https://zettelkasten.de/posts/building-a-second-brain-and-zettelkasten/

- https://fortelabs.com/blog/how-to-take-smart-notes/

- https://ericsandroni.com/book-summary-how-to-take-smart-notes-by-sonke-ahrens/

- https://heymichellemac.com/how-to-take-smart-notes-sonke-ahrens